Giving voice

The importance of ensuring that black men are heard

Kirk Harris remembers being a child growing up in Newark, New Jersey, when he first started having the questions.

Violence had erupted in several cities across the country during the turbulent 1960s. Harris saw it happen in Newark in 1967, when two white police officers beat and arrested a black cab driver after a traffic stop, spurring protests and unrest.

“I was a young kid, about 10 years old, and I was trying to process what was happening around me,” Harris says. “Why is this happening? Why are people telling me things should be a certain way, and not a certain way? I think that’s essentially what got me into planning.”

It was the beginning of a lifelong commitment for Harris, an associate professor of urban planning in the School of Architecture & Urban Planning, to find ways to strengthen black families. He advised former President Barack Obama’s administration and testified before Congress about issues related to poverty, family-strengthening and community development. And he continues addressing the issues through his research.

“When we build solutions, whether through planning or government interventions, too often, the last people we ask are the people experiencing the problems.”

Harris led a recent study that recommended government, corporate and philanthropic leaders should undergo regular training to help get a better understanding of what black men and boys need to create safe, healthy communities. The study was done through Fathers, Families and Healthy Communities, a Chicago-based organization co-founded by Harris that wants to help black men connect with their children, families and communities.

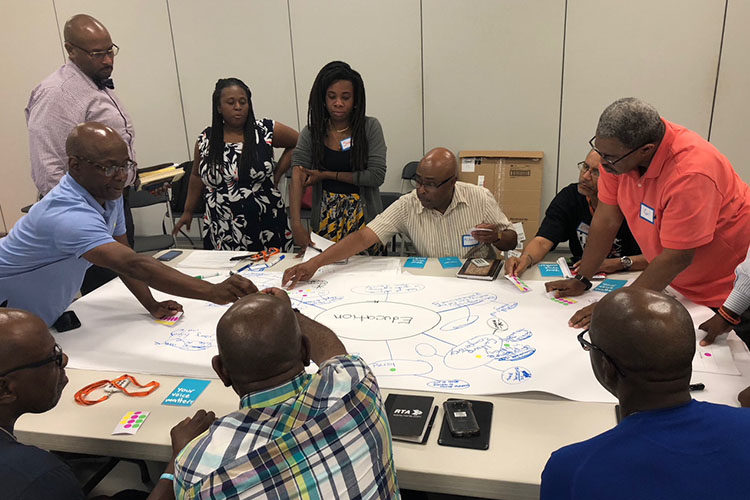

Although the research was conducted in Chicago, Harris says many of the findings are applicable to Milwaukee and other cities with large black populations. Researchers drew from dozens of hours of interviews during more than 80 community meetings with black residents between late 2016 and fall 2018.

“The study is really about community members offering their perspective on those things that constrain their day-to-day success, and how those constraints impact them and their families,” Harris says. “When we build solutions, whether through planning or government interventions, too often, the last people we ask are the people experiencing the problems. We felt that it was really important to ask the community about their perceptions of the challenges and get answers from them.”

The research presented several strategies to foster change. It offers solutions focused on understanding and breaking down barriers in areas such as the criminal justice system, education and housing.

This is important, the study says, because such barriers limit opportunities while threatening the lives and well-being of black men and boys. Challenges include violence and a lack of basic needs such as food, clothing and shelter.

“It’s getting to the point that a lot of us don’t want to be here. We are ready to go. I don’t want my kids here,” one study participant said in the report. Participants in the study were not named.

Those responses remind Harris of his own questions from more than 50 years ago, and drive his desire to make sure they’re not still being asked 50 years in the future. “You can’t hear those voices and feel less responsible to do something,” Harris says. “It’s too pressing, it’s too urgent, it’s too painful to not advance a sense of urgency about it.”

So Harris and his fellow researchers laid out what they call a “road map for social systems” based around the report’s findings and suggestions. Ideally, the social systems would listen, respond and be held accountable while integrating the solutions into communities.

Take, for instance, the suggestion about regular training so that organizational leaders better understand the needs of black men and boys. It’s aimed at building awareness about potential blind spots, then working to correct them. “It may be a lack of perspective and a limited appreciation of history,” Harris explains, “that confound an organization’s ability to create the change or equity that is often claimed or desired.”

But the training, which would be embedded within an organization, could both “deconstruct and reconstruct” organizational beliefs to help leaders understand the need for change. Leaders must first recognize the problem, work to understand why it’s happening and then work on a solution.

“For example, statistics indicate that black men and boys are the most underemployed, have the lowest graduation rates and are the most highly incarcerated,” Harris says. “Having a level of accountability is asking why this is happening combined with a commitment to turning around the systems that are creating these outcomes.”

The study also reports that black men and boys are motivated to serve as leaders in their neighborhoods. Moreover, they want to make sure they hold others and themselves accountable. “My strength is determination and creativity,” one study participant said. “I learn from the mistakes of others.”

Researchers outlined short-term goals that could be achieved within a year, such as enhanced community leadership and increased interest in the well-being of black men and boys.

Longer-term goals include increased integrity and follow-through on commitments to historically marginalized communities, as well as increased accountability and transparency when dealing with communities, especially black men and boys. There’s also a desire for strong, service-oriented black leadership and deeper examinations of systemic racism, and how it continues to replicate racial inequality and economic injustice.

“This kind of approach and practice is needed in every community,” Harris says. “What we are arguing for is a process – a process that taps into the community pain and community voice, and uses that as a building block.”