An early diagnosis

Helping parents and children learn more about an extremely rare disease

It’s a rare disease that renders children susceptible to constant joint pain and fatigue for their entire lives. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hEDS) is an inherited disorder marked by defects in a person’s collagen, a protein that helps form and support connective tissues. The condition has no known cure. It’s part of a group of connective tissue disorders more broadly known as Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Much about these syndromes is shrouded in mystery.

Unlike other connective tissue disorders, the genetic origin of hEDS hasn’t been identified. Experts have noted the relative lack of research into hEDS regarding genetics, proper diagnosis and patient counseling. The lack of knowledge is frustrating for both those affected by it and the medical community at large.

“Sometimes, parents don’t even know their kids have it. They don’t know what to do with it,” says Brooke Slavens, an associate professor in the College of Health Sciences. “There are a lot of unknowns, which is why parents come to the hospital for help.”

Slavens leads a UWM research team’s collaboration with the Genetics Center at Children’s Wisconsin hospital to characterize the features of hEDS. The disease is estimated to affect anywhere from 1 in 5,000 people to 1 in 20,000. By creating and developing a better understanding of it, researchers will be able to develop diagnostic criteria and treatment strategies.

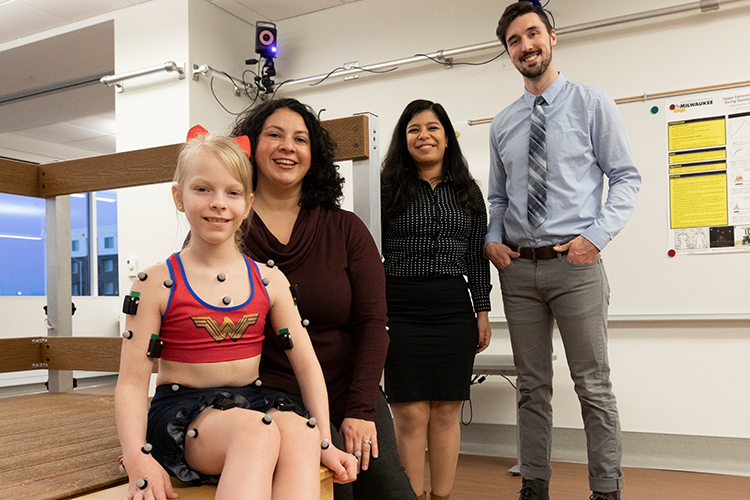

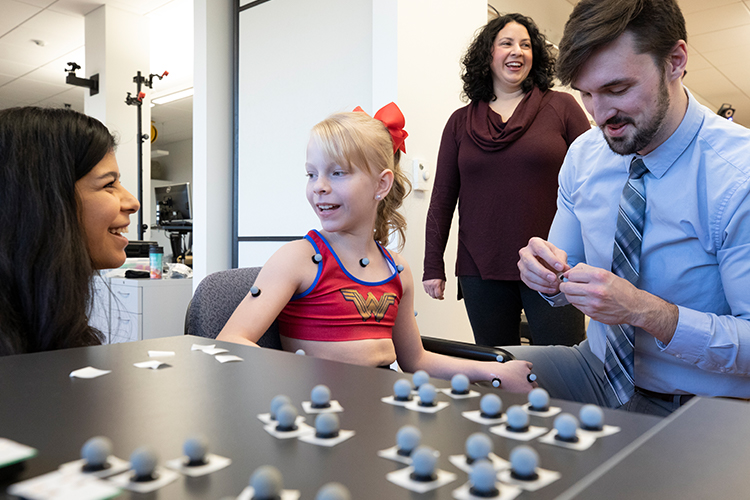

Much of the project’s clinical testing takes place at the Mobility Laboratory on UWM’s Innovation Campus in Wauwatosa. Slavens, who specializes in biomedical engineering as well as occupational science and technology, is the lab’s director. Using its state-of-the-art equipment, including motion-capture technology, she and her research team measure the movements of children with the disease.

The team’s ultimate goal is to devise better treatment and care plans for hEDS, the diagnosis of which is especially difficult. The most obvious symptom is an expanded range of joint motion, like an extreme form of being double-jointed. Beyond that, hEDS results in frequent joint dislocations, chronic joint pain, and skin that is extremely pliable and easily bruised, as well as other problems.

“With their skin being extremely stretchy,” Slavens says of children with hEDS, “it can lead to significant bruising and scarring. Fatigue is another major symptom.”

Joint hyperflexibility by itself is not all that unusual, occurring in as much as 25% of people in the United States. In children, it can mean having the ability to do the splits, bend their thumb to touch their forearm, or twist an arm behind their back.

Such flexibility might seem like a gymnast’s gift, but not for people with hEDS. Instead, hyperflexibility impairs balance, movement, strength and other functions while being a major source of pain.

Such flexibility might seem like a gymnast’s gift, but not for people with hEDS. Instead, hyperflexibility impairs balance, movement, strength and other functions while being a major source of pain.

Joyce Engel is a professor in the College of Health Sciences whose research focuses on the effects of and treatment for pain, particularly in children. As part of the hEDS project, Engel is collecting data by interviewing children with hEDS and their parents. She’s measuring the children’s chronic pain, whether it comes from the joints, from headaches and gastrointestinal discomfort, or from depression, anxiety and fatigue.

“The pain is there almost constantly,” Engel says, noting that it leads to sleep disorders, poor appetite and low energy, so many of the children are home-schooled. “If they do attend school, they can’t participate in gym class. They have to sit out recess. I can see that they want to do things, but it’s the pain that’s stopping them.”

Dr. Donald Basel is the medical director of Children’s Wisconsin’s Genetics Center and an associate professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin. He emphasizes the importance of creating the crucial biomedical phenotype, which involves quantifying the disorder – its physical characteristics and possibly its biochemical properties – by comparing people who have hEDS to those who don’t.

Researchers are also focusing on the genetics behind hEDS. “We’re collecting the genetic sequencing data,” Basel says, “so that we can analyze it and see if there’s any commonality between all of the patients, in terms of a genetic underpinning of the disorder.”

If researchers can identify a defect, it could guide them toward better support or treatment that holds potential to make a difference for patients and their families.

Although hEDS doesn’t affect life expectancy, researchers ultimately want to learn how to correct or eliminate the disease’s origins. They also want to find interventions that will improve the quality of life of hEDS patients.

That goes to the heart of what Slavens and her team are exploring in the Mobility Lab, where the focus is on evaluating the musculoskeletal symptoms.

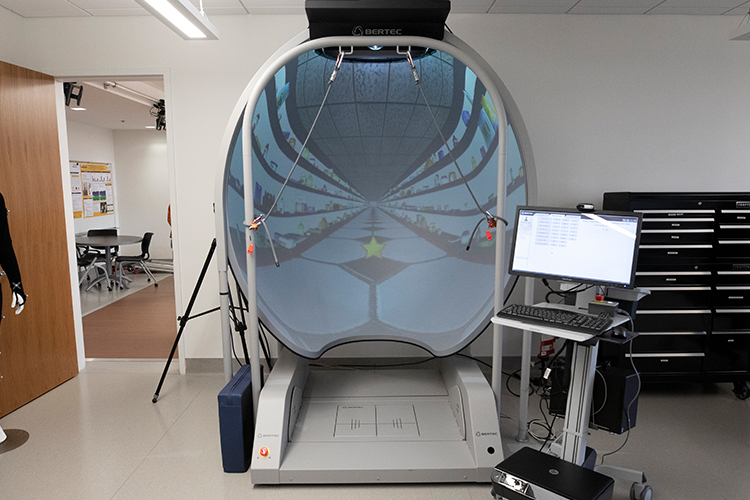

In one room, an array of 15 motion-capture video cameras mounted on three walls can track reflective markers affixed on the children as they move about, bending their knees, raising their arms, walking across the floor. An adjoining room houses a virtual reality apparatus that resembles a 10-foot, shell-shaped video screen. In front of it, subjects stand on a force-sensitive platform, balancing on one foot, reaching for virtual objects projected on the screen, and testing muscle strength and equilibrium.

These tests hold the promise of informing a helpful course of occupational therapy or assistive devices, such as braces and scooters. One idea being explored is using clothing or limb wrappings made of neoprene, a synthetic rubber-like fabric, that could improve posture control.

Additional therapy possibilities include relaxation techniques to ease pain or exercises to improve balance and endurance. Something as elemental as walking might prove to be an effective remedy.

Plans call for the project to include up to 20 children with hEDS and 20 typically developing children without hEDS. Since its inception in 2017, the project has received funds through Children’s Wisconsin and a College of Health Sciences Stimulus Project to Accelerate Research Clusters grant. Researchers have applied for additional grants.

“Our research is being driven by clinical questions,” Slavens says, “and a clinical need for solutions to help this group of kids.”