Greetings, BugFans,

As the BugLady was leaning over a pier photographing aquatic stuff last summer, she saw a mugging. Although she was right about the mugging part, she misidentified both the muggers and the mug-ee. She thought, erroneously, that she was seeing a pair of young water strider thugs attacking a guiltless Mirid plant bug. The two “water striders” rushed across a water lily leaf and grabbed the larger “plant bug” and scuffled with it, actually rolling it onto its back. As the BugLady snapped pictures, the “plant bug” managed to get away and exited across the leaf to the left, while the delinquents ran away to the right.

Fast forward eight months, when the BugLady was researching the Water lily planthopper (of recent BOTW fame). One reference noted that “Water lily planthoppers are preyed on by Water treaders.” Water treaders? When the BugLady looked them up, she recognized them. It turns out the young hoodlum bugs were Water treaders (not to be confused with the delicate Marsh treaders—a whole different animal). So was their intended prey.

Water Treader

Mulsant’s Water treader (Mesovelia mulsanti, named after a 19th century French entomologist-ornithologist) is fairly common in eastern North America but is easily overlooked and has a history of being ID’d as the nymph of something else. In the introduction to his 1917 publication The Life-History of Mesovelia mulsanti, H. B. Hungerford says that it “seems worthwhile to present some notes concerning the biology of Mesovelia mulsanti whose habits and life-history are certainly among the most interesting of all the bugs that walk upon the surface of the inland waters.” He proceeds, cheerfully, to do just that.

It is at home in the haunts of the marsh-treader on the floating vegetation growing in the shallow waters of the pools, where the clumps of sedge spread their slender stems upon the water from the bordering bank, where young cattails spring up and green algae carpet the surface of the waters. (Hungerford)

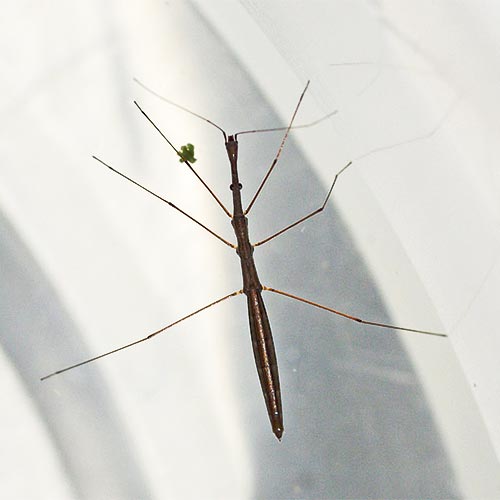

WTs are about 5 millimeters small (1/4” max), with long antennae, long legs, and a long face. Nymphs and most adults are silvery-green. Like the water lily planthoppers that they dine on, adult WTs come in uncommon winged forms or more-common wingless (there’s an “in-between” morph, too), and winged adults are darker with a white chevron on their backs. Their long legs allow them to scoot along pretty fast on the water’s surface and on vegetation, and to take little hops.

They have a simple/incomplete metamorphosis—a newly-hatched individual looks similar to an adult. Food-wise, what’s good for the adult is fine for the nymph, and they sport sharp, piercing mouthparts. Contemporary authors describe a fairly languid/passive hunting style, saying that WTs feed by scavenging dead or injured insects or insects that are stuck on the surface film (and that they may practice cannibalism). Earlier researchers like Hungerford tell us that “Water Treaders eat insects and other small invertebrates; their hunting method is to run along the surface of algae and duckweed, and even along the surface of the water, until they have run down their prey.” It is not surprising to see them on a water lily leaf with aphids.

They also reach down through the surface of floating mats of algae and other plants and snag tiny crustaceans and aquatic insects that feed and shelter there. When they catch something, they insert their “beak,” inject saliva/enzymes, and suck out their prey’s innards.

Hungerford again:

They are cautious creatures but do, on occasion, fall upon fairly lively prey. The tiny nymphs feed upon more gentle organisms in the water as there are few upon the surface that they are able to overcome. When offered springtails as suggested by Butler, disaster often followed…the hungry little creatures would attack them, only to be turned topsy-turvy upon the water even by comparatively small springtails.

WTs are eaten by fish and dragonflies, and nymphal water mites may parasitize them.

Ms. WT uses a specially designed ovipositor to pierce the stems of aquatic plants and ream out a hole. She may lay as many as 100 eggs, each requiring a separate incision (“As frequently as not the male accompanies the female during the process. Having mounted her in mating he merely moves forward and remains perched upon her back as she busies herself with egg laying, mating being attempted and often consummated between her labors.” Hungerford).

The plants that she inserts her eggs into sink to the pond floor in winter and according to some accounts, the eggs hatch in spring. There are probably several generations through the summer, but sources disagree about whether the final bugs of the year overwinter as eggs or as adults, hidden in the shoreline debris, bolstered by an internal antifreeze that keeps lethal ice crystals from forming in their cells.

WT vocabulary word—one of the two species of North American WTs that have found their way to Hawaii is troglophilic.

Where do WTs fit into the great scheme of things? Within the order Hemiptera, in the infraorder Gerromorpha (infraorder is one of those potential notches between order and family that’s used as needed). The Gerromorpha include water measurers, water striders, smaller/riffle/broad-shouldered water striders, and a few others. As a group, they are sometimes called “semiaquatic bugs” or “shore-inhabiting bugs,” and one author calls them all “pond skaters.” They are often seen locomoting across the surface of the water (including salt water— bugguide.net calls them the only true marine insects). How do they do it? A “hydrophobic” cuticle and hairs are standard equipment on the Gerromorpha, and their long, water repellant legs allow the pond skaters, whose weight is therefore spread out, to push down on the water’s surface without punching through. Check the indentations on the surface in the water strider picture (curiously, the claws of a water strider are located up on its legs in order to avoid slicing the surface film, but a WT’s claws are in the normal spot at the ends of its tarsi.).

Another WT vocabulary word is meniscus (the curve of the upper surface of a liquid, caused by surface tension). There is hardly a concept more important to aquatic invertebrates than surface tension. Because it is in contact with the air, that top layer of water molecules is “stickier” than those under it, and a certain force is needed to break through it, whether from above or below. The “meniscus effect” results in tiny, slippery hills where the water’s surface curves up to meet an “edge” of the shoreline, and of plant stems, leaves, floating debris, etc. (thanks to guest photographer Freda for the meniscus shot).

Life is Physics. The various creatures of the surface film have developed different ways to navigate the meniscus—WTs actually “run” at the meniscus slope and then use their front legs to pull themselves “uphill.” The BugLady recommends this beautifully-photographed article about bugs and the meniscus (you don’t have to do the math–the folks at MIT already did it for you).

Interested BugFans can find Hungerford’s article here.

The BugLady is confident that BugFans will look up troglophilic on their own.

Bugs in culture: “I was stunned by the perfection of the insects.”—Pablo Neruda

The BugLady