Howdy, BugFans,

The BugLady has been skulking about the Field Station of late, stalking invertebrates that hang out on the east wall of the lab. The wall is painted cinderblock that warms up in the morning and probably keeps some heat as it gets shaded in the afternoon. Grass grows right up to the edge of the building. The BugLady hypothesizes that bugs can enjoy the residual warmth without getting fried by the sun, because she sees some small critters on the north wall but very few on the bright south wall. She found some familiar faces and some new ones—plant-eaters and an array of carnivores that come to collect the herbivores. This was not a scientific study, just a random snapshot at a time (in late October and early November) when the bug season is closing down.

The BugLady practiced a little photomicroscopy in college—the subjects of her efforts then were amoebae—and apparently she still has a little photomicroscopy she needs to get out of her system (this time with a hand-held 50mm macro lens). Today’s bugs are closer to micro than macro sized; think of half-a-ladybug and then think smaller. The hump-backed springtail, which started the whole thing, weighs in at 2 to 3mm, and the spider mite is about the size of the smallest circle you can draw with a sharp #2 pencil. For scale, the dots on the white background are paint bubbles.

The BugLady is not very swift at identifying spiders and she doesn’t know who this is, but it’s a pretty little semi-translucent thing. She also photographed a fishing spider, either a wolf or grass spider, and several small black spiders that kind of resembled ants, a mimicry that comes in handy for predatorsm.

Jumping Spiders

Jumping Spiders (of previous BOTW fame) catch their prey by stalking and leaping, not by spinning a web, but they do lay down a dragline as they jump. The line suspends them if they hurtle over the edge of a flower or have to take evasive action from predators. This is a seriously small jumping spider, and the BugLady suspects that it may be Sitticus fascinger, the Asian Jumping Spider, an alien import that probably got to North America in the 1960’s from Russia and the Orient. Asian jumping spiders like man-made structures and they live for several years.

Damsel Bugs

Damsel Bugs (True Bugs in the order Hemiptera) show up in search of prey—fellow Hemipterans like planthoppers and leafhoppers, and anything else they might catch. Damsel bugs are found around the world in gardens and fields and under porch lights at night, and because they overwinter as adults, they are sometimes seen during the cooler parts of the year. This is one of about 15 species in the genus Nabis. Damsel bugs will eventually rate a BOTW of their own.

Braconid Wasps

Braconid Wasps lay their eggs on insects, where the wasp larvae live as parasitoids. Parasitoids spend their larval stage in/on the larva of other insect species, and various Braconids target specific groups—mostly butterflies, moths, flies, and beetles, but they will use bugs as hosts, too. The gradual gnawing away at the host from the inside or the outside keeps the host alive until the parasitoid is ready to pupate. The host may mount a chemical defense against its parasitoid, but many endoparasitic (internal) braconids carry their own defenses—polydnaviruses—that disarm their hosts’ immune system. Wowsers!

Red-banded Leafhopper

The orange “pi-shaped” mark on its thorax makes the BugLady think this is Graphocephala coccinea, a very spiffy 6 to 7mm leafhopper that is found in fields, gardens, and forests all across North America. With several color phases, it has common names like candy-striped/scarlet-and-green/red-and-blue leafhopper. Leafhoppers pierce plant stems and siphon plant juices. They can create sounds—very soft sounds—in a cicada-like manner. The BugLady listened, as she hunkered nose to nose with them, but the RBLs did not sing to her.

Clover Leafhopper

Clover Leafhopper (Ceratagallia sanguinolenta) (maybe). This stubby, dark leafhopper seems to be a Clover leafhopper, or a close relative thereof (this genus, which includes about 55 species, is being lumped and split as we speak).

[metaslider id=4601]

Although she is a pretty fair “picture-key-er,” the BugLady has not yet discovered the name of this very small (maybe 5mm), blushing X Leafhopper. Leafhoppers practice “simple metamorphosis”, with the youngsters hatching out looking pretty much like Mom and Pop. After about 6 molts, they have assembled the necessary adult body parts. Leafhoppers’ eyes are bigger than their stomachs, and the excess plant sap they ingest is expelled from the insect’s rear, sometimes under pressure, as a substance called honeydew. If you were standing really close, you might hear the tiny “POP.”

Piglet Bug

Where some insects never even get one common name, this handsome guy/gal (Bruchomorpha oculata) (probably) has three excellent names—the Piglet Bug, the Jimmy Durante Bug, and the Long-nosed Elephant Hopper. There are several families of planthoppers (planthoppers are distinct from leafhoppers but are also in the order Hemiptera) and the Piglet Bug family is Caliscelidae. This species is found from Quebec to Mississippi to Kansas to Minnesota, where it eats native grasses, especially Little Bluestem. It comes in short-winged (brachypterous) and long-winged (macropterous) forms, though one source calls them “flightless.” They are targeted by damsel bugs. Piglet bugs measure about 3.8mm (0.15 inches) in length. Several members of the genus, including this one, are listed as rare, uncommon or imperiled on Indiana prairies.

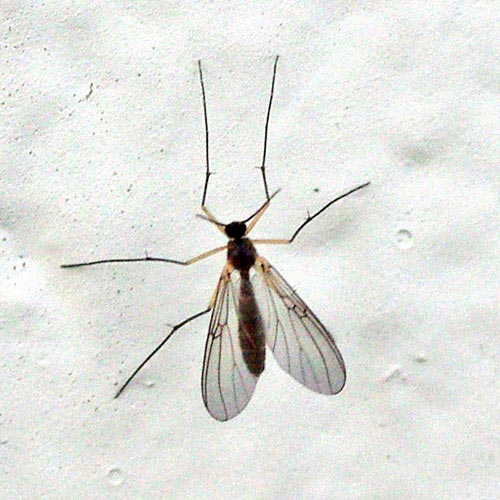

Fungus Gnat

This Fungus Gnat led the BugLady on a merry chase, taxonomically speaking. At first glance—a midge. The second glance said “No,” look at the simplicity of the wing veins and check out those spines on its legs! The BugLady flirted with crane flies and is now circling in the fungus gnat bunch, which includes the fungus gnats (Mycetophilidae), the predaceous fungus gnats (Keroplatidae) and the dark-winged fungus gnats (Sciaridae). She’s leaning toward Sciaridae, but at about 1cm, this bug seems a bit big for a Sciarid. Fungus gnats get their name from the feeding habits of their larvae (maggots)—decomposers who eat fungi, algae, or roots and who are considered pests when they inhabit potting soil, nursery growing medium, etc. The mosquito-sized-and-smaller adults do not bite (or feed), but they do pollinate flowers and spread mushroom spores.

Aphids

Aphids reproduce by parthenogenesis (virgin birth) most of the year, the young popping out without benefit of eggs. Generally, the late fall individuals are winged females that will mate and lay eggs that overwinter. The BugLady is not used to seeing aphids in mid-November, or alone, or looking quite as “leathery” as this individual with the twin tail pipes. Like planthoppers and leafhoppers, aphids sip plant juice, a commodity that is in increasingly short supply at this time of year. They are in the Order Hemiptera.

Bagworms

Bagworms are in the moth family Psychidae. Like caddis flies (which are not Lepidopterans but are not far off), bagworm larvae construct a case/home for protection (and for cooling, it seems that the temperature inside the case is lower then on the outside). Male bagworms emerge from their larval homes with wings, but females have no wings. From within their cases, females loose their siren pheromones and lure males to their larval shelter, inside of which they have matured and inside which they will lay their eggs. Psyche casta larvae (no common name for these guys) glue a few grass stems together longitudinally with silk to make a traveling house. The whole case is about a dozen millimeters long. Psyche casta made its way here from Europe in 1931, spreading out from Boston. Its food plants are variously described as grasses, birch, willow, and poplar or as grasses, mosses, lichens and other low plants, and they sometimes nosh on the scale insects that feed on their host plants.

Plaster Bagworm

Here’s where it gets confusing. The Plaster Bagworm (Phereoeca uterella) (a.k.a. Household Casebearer Moth) is actually in the clothes moth family Tineidae. These larvae use silk to piece together a variety of materials, depending on whether they live indoors or out, and they enlarge the case as they grow. Outdoors, they are often found on walls and underneath buildings, and they make their case from sand, rust flakes, soil, hairs, frass (bug poop), etc. Inside, they prefer furniture and carpets and the case is built with fibers, grit, hairs, bug parts, and other stuff the vacuum missed. The 12mm long case is open at each end, and the larva can turn around inside its case and stick its head out either end. Though they eat tiny bits of detritus and dead insects, their main food is web produced by spiders and insects, even the cast-off cases made by their brethren. Indoors, they might eat some woolen fabric; outside, they sometimes feed on fungus.

And then, a bit more confusing. The BugLady named this critter the “casemaker bagworm” because she isn’t sure whether it’s a case-making clothes moth or a bagworm, so she’s covering all the bases. Whatever it is, it was common in the final days of October.

Spider Mites

The BugLady almost missed the spider mites, the smallest wall critter she could see. They are probably clover mites (Bryobia praetiosa). Those aren’t antennae—the long front pair of their four pairs of legs typically precedes them. Spider mites are plant feeders that are considered pests when present in large numbers (the BugLady doesn’t know how you could tell). Though they eat grass, they may invade homes in spring (as one source points out, they’re so small that they can walk right through a window screen). They usually leave voluntarily after several days, and squishing them leaves teeny tiny red stains. Discourage them by keeping a two foot wide, grass-and-clover-free strip around the sides of the house. According to Borrer and DeLong, in An Introduction to the Study of Insects, unfertilized spider mite eggs hatch into males, and fertilized eggs hatch into females.

Hump-backed Springtails

The BugLady is notoriously far-sighted and enjoys the surprises that photo-editing brings. She photographed the Hump-backed springtails (Lepidocyrtus paradoxus) and was clueless. “What’s shiny green and tubular and hangs on a wall?” isn’t a very catchy riddle. Thanks, Chris, as always, for the ID. At Bugguide.net, most of the pictures of HBSs come from the East coast, with just a few from Iowa and Minnesota. They like marshy or woodsy habitats and they also occur in Europe. If emerald green isn’t spiffy enough, they also come in silver (Species Lepidocyrtus paradoxus). Springtails get their name because of their ability to leap high (but randomly) into the air when a “clothespin” gizmo under their abdomen is released. Springtails eat tiny organic bits they find in the soil. Unlike most insects, they continue to molt after reaching adulthood.

Whew! Who knew! There were also ants, red velvet mites, nymphs of box elder and other seed bugs, various little beetles, and moths.

What’s the point? The BugLady wonders what is on this wall in June and July. The BugLady wonders what’s on your walls. Imagine what could be found if everyone would look just a little closer at the walls we pass every day!

The BugLady