Howdy, BugFans,

Wakingsticks

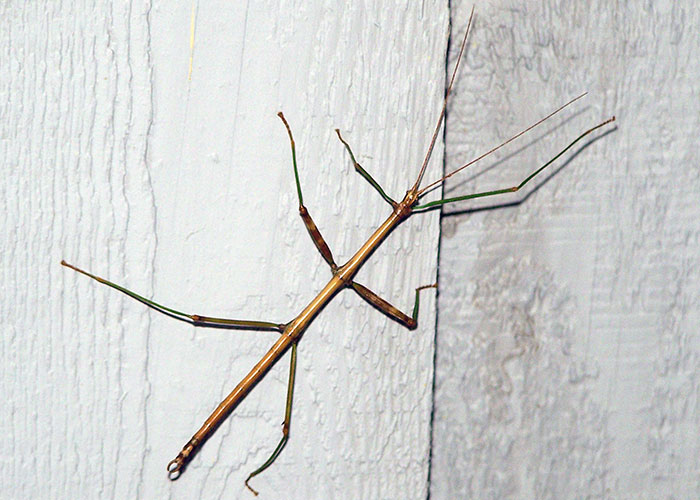

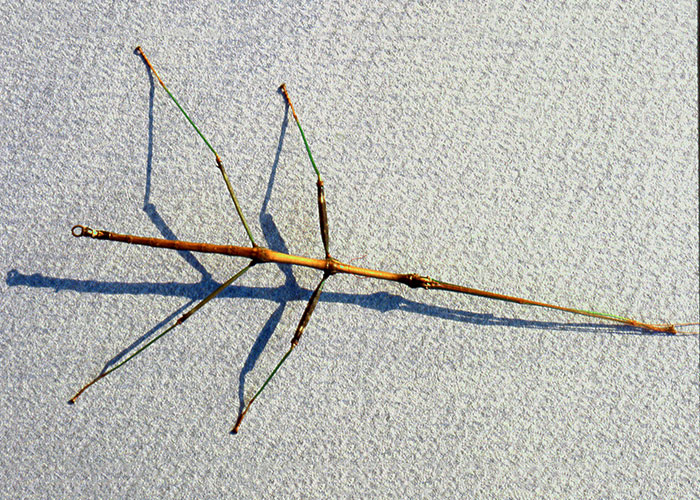

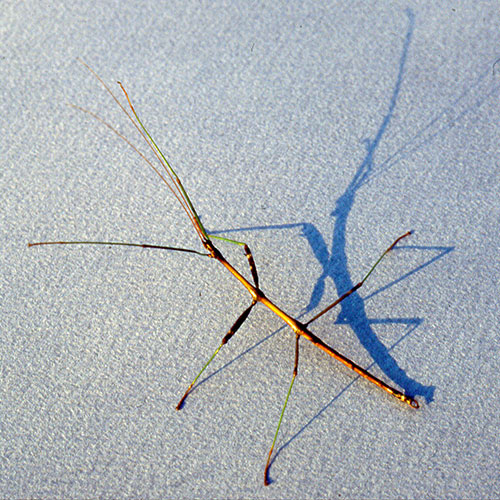

Walkingsticks are available in green or brown (a few species can also change color slowly, and the BugLady has slides of a really spiffy individual that mimicked the speckled and streaked shoots of a box elder). Local walkingsticks may reach 4” in length (males tend to be smaller) but the largest North American species can grow to a whopping 7 inches, and tropical species may reach 12 inches. Most species are wingless. Since insect legs (and wings) are attached to the middle section, or thorax, it’s apparent that a walkingstick’s thorax comprises an impressive portion of its body. A walkingstick that loses one of those spectacular legs is able to regenerate it, completely or partially.

Shy and nocturnal, they graze on leaves of forest trees and, during a population boom, can damage them. There are two reasons for camouflage—to hide and to hunt. Along with their physical appearance, walkingsticks practice “behavioral camouflage.” During the day they extend their front and rear legs to the fore and aft of their body and remain motionless or sway slightly in the breeze. Turns out that despite one of Mother Nature’s better camouflage jobs, many predators aren’t fooled; walkingsticks are spotted and eaten by a variety of songbirds, rodents and mantises. Two species of Florida walkingsticks have added chemical warfare to the usual arsenal of passive defenses, squirting a highly irritating liquid into the face of a potential predator and earning themselves the nickname “Musk-mare.”

As females negotiate the trees in early autumn, they drop eggs that free-fall to the ground. These will hatch next spring—or the one after that. Metamorphosis is Simple/Incomplete—the newly-hatched young pretty much resemble the finished product, simply growing (often changing color,) and adding adult parts as they molt. Some species, like the aphids of recent BOTW fame, practice parthenogenesis (virgin birth).

Formerly classified, along with the Mantises, in the grasshopper Order (Orthoptera), Walkingsticks are now in their own Order, the Stick Insects or Phasmatodea.

The BugLady was casting about for one final interesting factoid with which to finish this account, and she discovered two, in The Handy Bug Answer Book by Dr. Gilbert Waldbauer:

- First, parental care is necessarily absent in a group where Mom drops her eggs to the ground from the tree tops, and the forest floor is fraught with dangers for the hapless eggs, including cuckoo wasps that search for walkingstick eggs to parasitize. Because a portion of the outside of each egg is edible, ants carry the eggs below-ground to their nests. Their nibbling does not damage the interior of the egg, and when the tiny walkingsticks hatch, they are allowed to exit the ant hill.

- The second factoid includes some “adult content,” and the BugLady requests that you cover the eyes of impressionable children and innocent maidens—if you know any. Fidelity is rare in the insect world, and there are a number of strategies that males of some groups may use to ensure that the object of their affections does not court another. Some male walkingsticks are known to, ah, remain “in the embrace” of a female long after sharing bodily fluids with her, becoming what Waldbauer calls “living chastity belts.” In fact, the, um, endurance record for copulation for the insect world seems to be held by walkingsticks.

Seventy-nine days.

The BugLady