Howdy, BugFans,

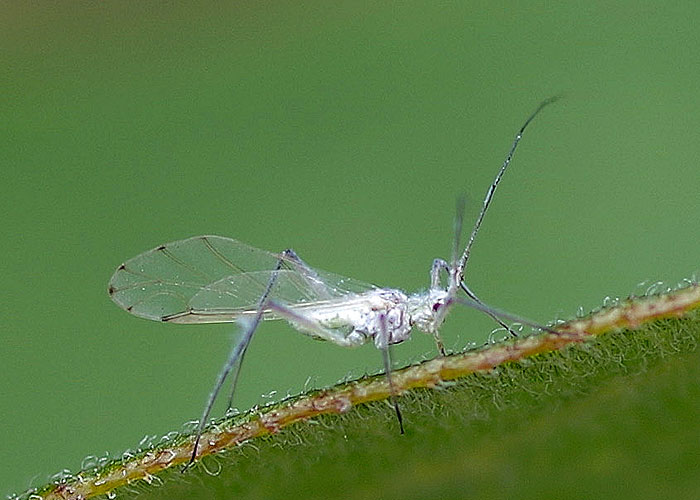

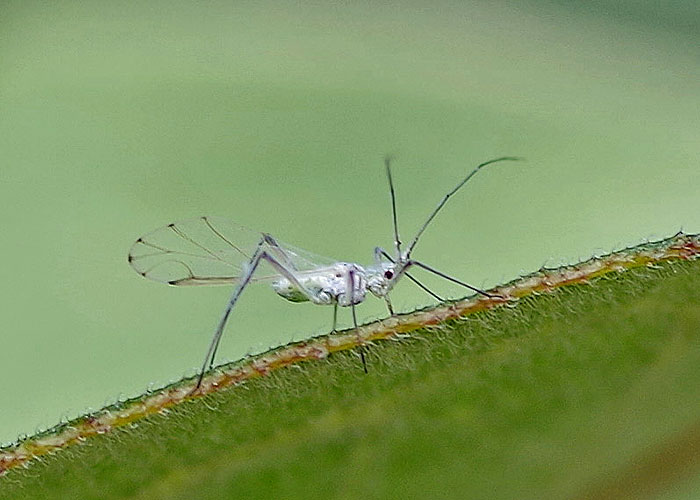

This bug is so exquisite that it’s hard to remember that it’s an aphid. It’s the winged phase; non-winged individuals are, depending on the species, blob-shaped, sesame seed-shaped, or spidery-looking insects seen en masse, sucking juices from the tender parts of plants. Species of aphids are often associated with specific host plants.

Tree Aphids

The BugLady is going to go way out on a limb here, where taxonomists fear to tread, (she’s so far out that she can’t even see the tree trunk) and guess that this might be in the genus Euceraphis, and she’s going to pretend that the species is papyrifericola to see just how far out, note that the expert at bugguide.net says

Tree aphids are not my strongest area, but I have collected off Betulaceae [birch] enough to know that what I think might be Euceraphis often turns out to be Calaphis when seen mounted on slides. I have little experience with them in the field, and cannot confidently recognize the genera from photos… So, my recommendation is to not put a genus name on many of them in any confident way.

But, for the sake of argument, Euceraphis will open a door onto the tree aphids. The family Aphidae has about 4,700 species (so far), many of which are not major plant pests. Tree aphids are in the subfamily Calaphidinae (a bunch of deciduous tree feeders) and Euceraphis is in the tribe Calaphidini (mainly birch/alder-feeders, and there were birches nearby) (quick aside—Google offered to find for the BugLady some words that rhyme with Calaphidini, and the BugLady couldn’t resist, but they turned out to be words like “eeny,” “teeny,” “weany,” “meany,” and “beany”). There are lots of hits for “tree aphid,” but most sites lump them, discussing generic aphid lifestyles, symptoms of their presence, and bug control, rather than who’s who.

Generic Aphid Lifestyle

Aphids are poised to take over the world. Their reproductive strategy involves legions of females that move around on plants, popping out female young (already nymphs—they skip the egg stage) parthenogenetically (with no male “input”). These clones mature quickly and soon produce their own young. This is why naturalists joke that a female aphid who starts at the bottom of a stem is a great, great grandmother by the time she reaches the top (one species of rose aphid has been clocked at up to 15 generations per growing season). Aphids are designed to cash in quickly on the nutritious new spring growth.

Aphids are generally wingless until an overcrowded plant/deteriorating plant quality signals them to produce winged forms that can migrate to nearby vegetation. They have no “search image”—finding their host species is a matter of chance—so they often wind up on non-host plants accidentally. They are all female until, at the appointed time of the year for each species (usually fall), females will produce winged male and female nymphs. Romance ensues, and so does genetic diversity. Females subsequently lay eggs that overwinter and produce more females in spring, and the beat goes on.

Symptoms

They suck juices from leaf veins, buds, and new twigs. A healthy tree can shrug off the usual level of feeding, but a large infestation can cause brown/curled/wilted leaves and dieback of new shoots and even kill a plant, especially if aphid numbers are high for several years. Excess sap flows out the other end of the bug; it’s sugary, and other insects congregate to feed on the “honeydew” that falls on leaves. Humans are less enthusiastic about the sticky, hard-to-remove-once-it’s-dried stuff on their cars and patio furniture. And honeydew is a great growth medium for an unsightly “sooty mold” that grows on the leaves. With honeydew as a pay-off, some kinds of ants “farm” the nymphs of many kinds of aphids, but not those of Euceraphis.

This individual looks a bit fuzzy. Many adult Calaphidini are initially a lovely, pale green, but, says the Report by the State Entomologist of Minnesota to the Governor, Volume 17 (1919), “Some of the species [of Calaphidini], at least, are further characterized by wax glands on the body, legs, and antennae, which secrete an abundant, white waxy substance in tufts or bands that give them a very peculiar appearance and may serve as protection against some of their enemies.”

Members of the genus Euceraphis have divvied up the birch species and do not poach, even when a tree and its aphid are relocated to a different country. Euceraphis is notable among the tree aphids because all adults, not just a dispersal generation, are winged. According to one source, Euceraphis stops reproducing in mid-summer as leaves mature, and then resumes in fall as sugars in the leaves are being broken down and sent to the roots.

Tree aphids are kept in check by birds, crab spiders, a variety of insect predators like lacewings, syrphid fly larvae, and ladybugs (both adults and larvae). Several small wasps parasitize them, and they are subject to (vocabulary word of the day) entomopathogenic (bad for insects) fungi.

And what about Euceraphis papyrifericola? Large for an aphid at just under three-eighths of an inch, it specializes in paper birch (Betula papyrifera), though it’s unusual because it may sip on gray birch and, when in Rome, on a European alder.

The BugLady