Howdy, BugFans,

It’s a good thing that the BugLady doesn’t have nearby neighbors (or a Home Owners’ Association) who might be alarmed about someone who turns on the porch light and then creeps around taking pictures of porch critters at midnight.

Let’s back up a bit—what’s up with insects and lights? There’s no simple explanation, and there’s no theory that is universally embraced by the entomological community (and some ideas are actively “pooh-poohed”). First of all, many organisms have a strong love for the light (a positive phototaxis ) or a strong avoidance of it (a negative phototaxis). It doesn’t fall out cleanly along nocturnal/diurnal lines—some daytime critters flee the light and some nighttime animals embrace it. What do scientists and the popular press say?

- The most popular theory is that nocturnal insects (most studies are done on moths) navigate by the light of the moon. Because the moon is so distant, their orientation compared to the moon is “fixed” in their navigational apparatus. According to the theory, when they see the BugLady’s porch light, it’s too close, and the light-to-eye angle changes too rapidly compared to the distance flown, confusing them and preventing them from flying in a straight line. While the moon’s rays are almost parallel as they hit the earth, the rays from the porch light beam out in all directions, causing confusion. Besides which, the porch light is brighter than the moon and may interfere with a moth’s ability to see the moon.

- An associated theory says that the eye that receives the most intense light sends a signal to the wings on one side of the body to beat harder and the moth spirals. One scientist discovered that moths fly straight toward light from a distance and adopt avoidance behavior when they get close.

- Some researchers think that nocturnal insects tell up from down by the gradations of light from night sky to shadowy ground (to a moth in danger, “up-toward-the-light” seems to be the desired escape route).

- The type of light makes a difference; insects may be sensitive to lights of certain intensity and wave length. Ultraviolet light is good, and so is white light (which explains the sale of yellow porch lights in summer). Do the wavelengths of different kinds of light cause behavioral disorientation?

- Insects are cold-blooded, and some suggest that they need the heat of the porch light to jump-start their thermostat. But, studies show that cold UV lights attract more moths than “warmer” bulbs. In the BugLady’s experience, our recent, cool nights make for an empty porch.

- Some scientists say that the lunar cycle influences insects. Researchers captured fewer insects with light traps when the moon was full and more in the dark of the moon. In another study, researchers found that mosquitoes were more active during a full moon.

- And then there’s the Evolution card. Some theorize that we’ve been putting up lights only very recently in the moths’ evolutionary timeline, and they just haven’t had time to adapt to us yet. The BugLady discounts this one because like many insects, moths have a one year life cycle, and adaptations can enter the population pretty fast.

- Another guess is that since nocturnal animals pack it in when the sun comes up, they are always on the lookout for signs that night is ending. They fly to the porch light and eventually settle down next to their own personal sun.

At any rate, the BugLady’s nocturnal excursions have yielded pictures for a number of BOTWs (and have thrilled the cats, who wait at the door for misguided moths that fly in). Here’s what’s up and about in the wee hours these days (not including the many mini-moths that the BugLady has fun stalking but cannot identify). Yes, the BugLady is aware that her porch needs washing/painting and her window screens are showing their age. Volunteers are welcome, any time.

The Horrid Zale Moth

Who can resist a moth named The Horrid Zale? John Hubner, the German entomologist who named it Zale horrida in 1818 must have been a Latin scholar—“Horrid” comes from horridus, which originally meant bristly or rough. Its caterpillars feed on viburnums, especially Nannyberry, which grows not far away in the BugLady’s field. For great images of the horrid bristles, try here on the site.

Snout Moth

Some of the Snout Moths didn’t get the memo about proper wing-folding. The BugLady suspects that this beautifully-marked little (3/4”) guy/gal is the Eastern Grass-veneer Moth, Crambus laqueatellus, one of 40 or so similar-looking species in the genus. As its name suggests, its caterpillar feeds on grasses, which the BugLady has, in abundance, close to her porch (though one maverick source says they eat mosses).

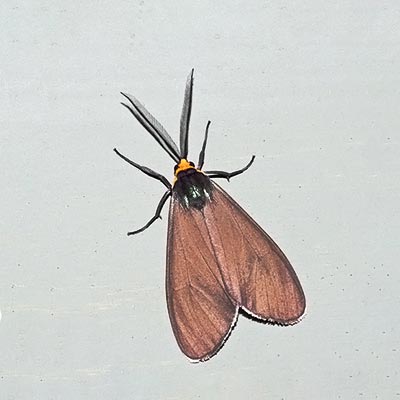

Virginia Ctenucid Moth

The Virginia Ctenucid Moth (the “C” is silent like the “r” in “fish”) is a day-flying moth that is often mistaken for a butterfly because of its bold flight (like most moths and unlike most butterflies, it lands on the underside of a leaf).

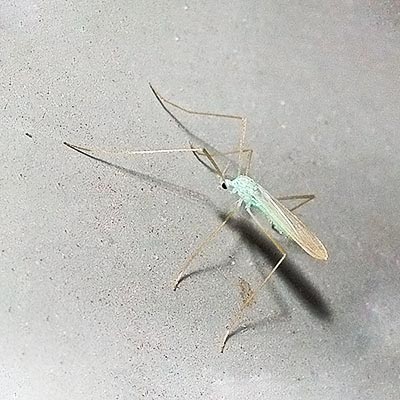

Crane Fly

The green Crane Fly comes with the fantastic name Erioptera chlorophylla. Crane fly larvae live in damp-to-wet lands ( Erioptera like organic mud) but the adults range far and wide and are often seen on window screens. The BugLady came across a 1913 account from Orono, ME which informed her that when these green beauties are dropped into boiling water, their color disappears. The BugLady can only speculate that they were mistaken for lobsters.

Daddy Long-legs

Daddy Long-Legs are common hunters on the front porch, by day and by night. If one picture is worth 1,000 words, then these two tell quite a story.

[metaslider id=4720]

Stonefly

This large Stonefly had to travel some distance to get to the BugLady’s front porch. Their young (naiads) (aka “trout food”) reside in unpolluted rivers and streams, where they breathe with gills in their “armpits” and at the base of their two tails.

Masked Hunter

The Masked Hunter, of previous BOTW fame, is an assassin bug that made its way here from across The Pond and now ranges across North America. When one of the BugLady’s dust bunnies starts walking, it’s the nymph of the masked hunter. Dust, lint and dog hair attach to their sticky exteriors, providing the perfect camouflage. Its prey here is a small ichneumon wasp.

Mosquito

Finally, a glamour shot of Wisconsin’s state bird, the Mosquito, a constant companion on the porch at night and elsewhere during the day. Female mosquitoes, famously, enjoy a blood meal in order to lay eggs, while males feed on plant juices. Male mosquitoes have fabulous antennae, which they use to tune in to the whine of a female’s wingbeats. When a guy and a gal meet, they adjust the pitch of their hum by increasing/decreasing the speed of their wing beats—until they are humming at the same pitch.

Check out a recent post by insect blogger Dragonfly Woman, on a few of the many citizen science projects involving insects.

The Bug Lady