Greetings, BugFans,

In his youth, the BugLady’s husband was allergic to the sting of sweat bees. When his mom took him to the doctor to find out if there were de-sensitization shots, the doctor’s reaction was—“Sweat bee?” Probably a tribute to the ubiquity of this small, globally common bee and to the Allergist’s credo—“Anything can do anything.”

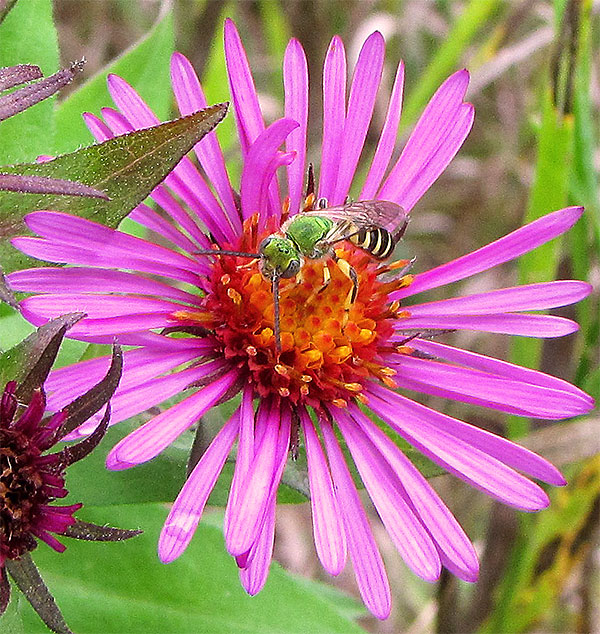

Sweat Bees

Sweat bees, in the family Halictidae, are found on flowers (which they pollinate), feeding on nectar throughout the growing season. Sometimes they camp out near aphid colonies and feed on the honeydew that is an aphid by-product. Like bumblebees, they can collect pollen using a process called “buzz pollination” (sonication). When a bee grabs the anther of a flower in her mandibles and uses her wing muscles to vibrate the flower, the pollen is dislodged. Like shaking a wet tree.

Their name stems from the habit of members of one drab genus, Lasioglossum, to land on your sweaty skin and lap up the salt. The process goes well until their salt-source (you) makes a sudden move or tries to swat/brush them off. According to Wikipedia, “their sting is only rated a 1.0 on the Schmidt Sting Pain Index, making it almost painless.” (Google it—it’s fascinating, in a voyeuristic, masochistic, and kind of creepy way).

Socially complex ants, honeybees and paper wasps get all the press, but most Hymentopterans live solitary lives. Depending on their species, sweat bees are labeled solitary to semi-social; the offspring of some kinds of sweat bees stay with their mother, helping care for the nest and young. Sweat bee society is totally female until males are produced in late summer/early fall.

Nests are made underground or sometimes in wood—females of species that are somewhat colonial share a common entrance, but each individual in the colony “owns” her specific tunnel within the system. Eggs are placed in cells with a cache of pollen and nectar and the entrance is sealed. Accounts differ concerning the timing of the nesting effort. Some references say that a female mates before winter and starts excavating her nests in spring. Other sources say that sweat bees overwinter as larvae and pupae. In The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects and Spiders, Lorus and Marjory Milne state that a female who is returning from a foraging trip to a communal nest with her legs covered with pollen is given the “right of way” over out-bound bee traffic.

The BugLady