Salutations, BugFans,

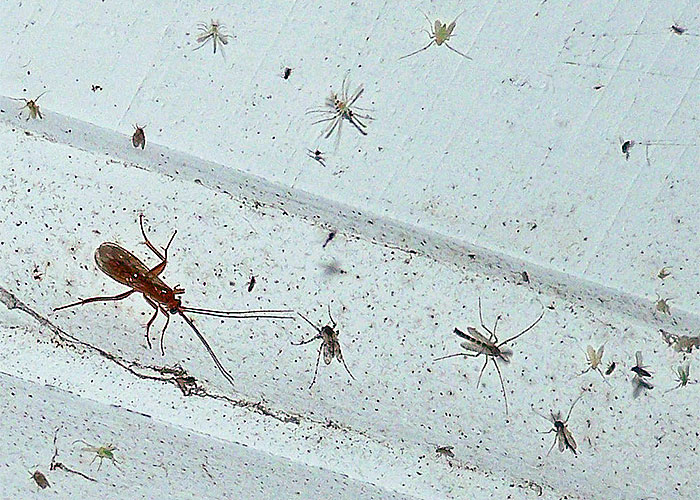

The BugLady lives near the Cedarburg Bog, where we are serious about our Bugs, but she would like to reassure you that clouds of midges are an often misunderstood and distinctly non-vampire-ish assembly. Big flocks of small flies—even of mosquitoes—tend to be bastions of (non-biting) male solidarity, which means that aside from the possibility of inhaling a bit of flying protein, it’s safe to immerse yourself in a herd/flock/bevy/pride/pod of midges. Check out the chapter on Midges in the excellent A Guide to Observing Insect Lives by Donald W. Stokes for information about masses of midges and about the tendency of some species to orient over a “swarm marker” and stay within a midge-eyesight of it.

Swarms are like big singles-bars, crowded with males hoping to attract females. If a female does enter, she pairs up with a guy and they leave together. He subsequently returns to the group while she’s out laying eggs. The BugLady senses a cosmic “eye-roll” from female BugFans.

Midges

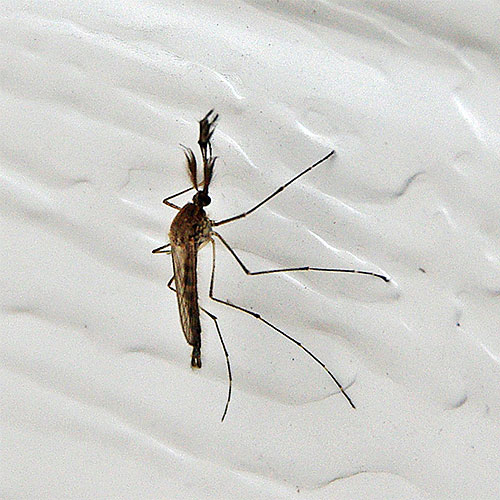

Midges, in the family Chironomidae, are mosquito doppelgangers. Midges hold their wings out to the side a bit when at rest, and mosquitoes tuck theirs over their backs. While either may rest with only four feet on the ground, mosquitoes raise their back pair of feet and midges tend to lift the front pair. The BugLady hasn’t yet convinced a midge to sit still for a clear portrait, but midge antennae tend to be even more feathery than those of the stand-in male mosquito pictured here. The male’s fancy antennae are tuned to the high-pitched frequency produced by the female’s wing beat, and he can hear her sound even through the hum of the “frat party.”

Midges can tolerate pretty cold weather, bouncing up and down in the air of early spring and late fall, especially near wetlands (their rapid wing-beats raise their body temperature). Adults are harmless; they live only days/weeks (adult Chironomids do not eat), but midges “take the rap” for the actions of other Dipterans like mosquitoes, blackflies, no-see-ums, and punkies/gnats.

Their larvae/maggots may live for up to three years in habitats that range from damp edges to depths of many fathoms in both salt water and fresh (fathom, a measurement of about 6 feet, comes from the Old English word faethm meaning “outstretched arms” or “the length of outstretched arms”). There they prey on mini plants and animals and scavenge on organic debris. Kaufman and Eaton, in Field Guide to Insects of North America, say that many larvae build tubular retreats by gluing together small particles using globs of mucous, a neat trick, underwater. Red hemoglobin found in some species gives them the nickname “bloodworms;” the extra hemoglobin lets them pick up oxygen more efficiently in habitats where there isn’t much of it. Bloodworms are a huge part of the diet of many fish (and so are available in pet stores), and fish leap out of the water to snag adult midges dancing above its surface, though the BugLady can’t imagine that “midge calories gained” make up for the “leap calories used.”

Keep in mind, as you navigate the earth, that depending on whose book you read, there are 200,000 to 2,000,000 insects (that’s individuals, not species) for every man, woman and child on the planet. The BugLady’s are all mosquitoes and deerflies, and they all live in the Cedarburg Bog. And next to her clothes line.

The BugLady