Salutations, BugFans,

Occasionally, one of the BugLady’s wee dust bunnies becomes a little more animated than the rest of them—a situation that is startling, momentarily, until she remembers the Masked Hunter (Reduvius personatus), an alien from Europe and Africa that is now found throughout the U.S. The adult is a striking, shiny, black bug about 3/4” long. The immature (nymph) has a sticky “finish” that attracts lint and dust; in short, stuff sticks to Junior, earning it the nickname “dustbug,” and camouflaging or “masking” it from its predators. One correspondent on www.whatsthatbug.com submitted a photo of a blue immature that was found in a blue shag carpet; another referred to them as having a “tempura-like” coating.

Masked Hunters

Masked Hunters, in the order Hemiptera (True Bugs), are in the family Reduvidae, Assassin bugs, a group of active and ambitious hunters that stalk primarily insect prey and will go after critters that may be larger than they are. They dispatch their prey by stabbing it with their short beak (rostrum) and injecting it with potent chemicals that both paralyze their catch and soften its innards so they may be slurped out.

A sub-family of Assassin bugs (but not the Masked Hunter’s group) includes bugs called “Kissing Bugs”—the ultimate in image ambiguity. They feed on the blood of mammals, including humans, and a few are notorious disease vectors; their nickname derives from their targeting the thin skin on their victim’s face, especially the lips, often while said victim is asleep. The debilitating and potentially fatal Chagas disease of Central and South America is spread by these Kissing bugs, which bear a family resemblance to the Masked Hunter.

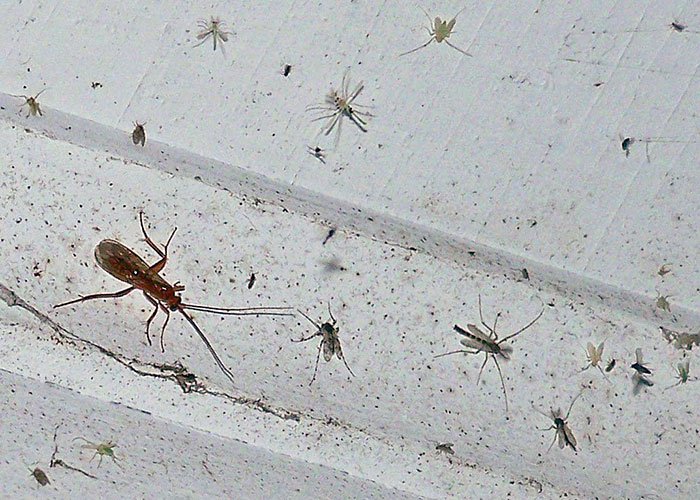

The good news is that Masked Hunters are insect-feeders, untiring consumers of bedbugs, a pest that is staging a comeback in big cities everywhere thanks to the ease of world travel. The bad news is that they are untiring and, according to some references, nearly exclusive consumers of bedbugs, and these authors suggest that if you have the predator, perhaps you should check for the prey! (Masked Hunters also live in nest colonies of Swallows, dining on small bedbug-relatives called “Swallow bugs”). The BugLady sees Masked Hunters on early summer nights on her front porch, to which they and hundreds of other insects have been attracted by the light, and has read that sowbugs, lacewings, flies, carpet and grain beetles, and earwigs show up on their dinner plates, too.

Handle With Care!

Masked Hunters and their relatives are not aggressive toward humans (and most do not spread disease), but they can defend themselves effectively if manhandled. The same beak that is so lethal to their prey can deliver a poke that is described by Eaton and Kaufman in their Field Guide to Insects of North America as “excruciating” and by other references as “like a snakebite,” “painful enough to cause immediate faintness and vomiting” and as resulting in longer-term swelling, blood blisters and irritation. The “Kissing Bug Scare of 1899” (True story! Google it!) was apparently caused when these guys (or their relatives the Black Corsairs, sources disagree) experienced a population boom in the northeast, entered houses in large numbers, and inflicted bites as people brushed them away from their faces.

When they’re not feeding, assassin bugs bend their heads slightly downward, resting the beak/rostrum in a short, ridged grove between their forelegs. They can produce sound by rubbing the beak-tip across these ridges. More Stridulation.

The BugLady