Howdy, BugFans,

For those of us of “a certain age,” (and before the notoriety of these new-fangled aliens like kudzu, zebra mussels, fire ants, and the emerald ash borer) the Japanese beetle (JB) will always be the poster child for Invasive Species.

Their story is classic. They arrived in New Jersey from Japan in 1912 hidden in a shipment of iris bulbs, but they weren’t noticed until 1916. When JBs came to North America, they left their natural enemies at home. In their first 8 years in the Land of the Free, and despite the control methods of the time, their range expanded to an astounding 2,500 square miles. They are presently well-established in all states east of the Mississippi except Florida and are making inroads in the West via shipments of plants. Like the mutants in horror movies, they just keep coming, despite the heavy fire power we lob at them (and in the case of the JB, that includes imported pathogens, parasites and predators).

Like all successful invaders, they are generalists. They have been recorded as eating some 300 species of plants (sources give numbers between 200 and 400). Woody? Herbaceous? Vine? Flower? Doesn’t matter.

Japanese Beetles

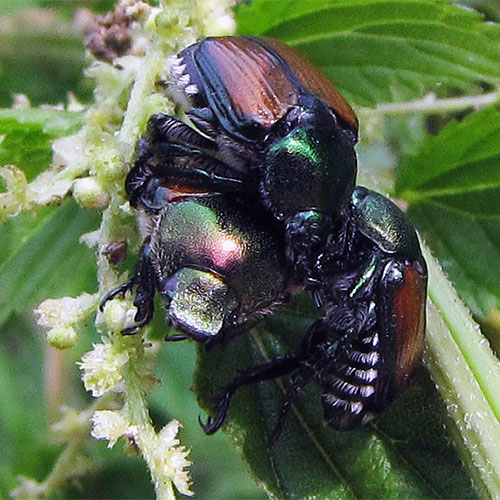

The Japanese Beetle (Popilla janponca) is in the Scarab family, Scarabaeidae. If it weren’t the Beetle from Hell, we would admire its beauty and survival powers. It’s a chunky half inch of beetle with a shiny green thorax and burnished bronze elytra (wing covers). Five short, vertical, bright-white stripes of hair decorate the abdomen, and it sports two more white tufts like twin exhaust pipes. It is diurnal (active during the day) and likes to feed in groups.

The adults are primarily leaf skeletonizers, eating the soft tissue that lies between the tougher leaf veins, creating green lace (there are native leaf skeletonizers on the landscape, too). The adults’ Top 50 also includes roses. The larvae (grubs) feed underground on a variety of roots, especially those of horticultural and agricultural plants and turf grass (they’re a pain at golf courses). When they are working on a lawn in good numbers (1,500 grubs per square yard of sod have been recorded), the ground may feel a bit spongy underfoot.

Mom lays her eggs in sod in mid-summer. The kids hatch and spend the next 10 months as grubs. They are full-grown when winter comes, and they overwinter as grubs in the soil, burrowing farther down as the frost line reaches deeper. They pupate in spring and emerge in mid-summer (they prefer warm, sunny, calm, moderately humid days). As the first JBs emerge and start to feed, they emit a scent—a pheromone—that attracts more and more adults. Females release a different pheromone to lure males. During their two months as adults, they can wreak havoc.

The adults are eaten by starlings (another alien), and when there are large numbers of grubs in your lawn, moles, skunks, Canada geese and raccoons make an appearance to excavate for them. Biological controls that are being used include parasitic tachinid flies and tiphiid wasps (whose larvae go after—literally—the JB larvae)

And now, in the Don’t-Put-Anything-in-Your-Ear-Smaller-Than-Your-Elbow category, a cautionary tale. A friend had a very Close Encounter with a Japanese beetle that flew into his ear while he was mowing the lawn (not normal behavior for JBs, as far as the BugLady knows). This one’s for you, Mike. Instead of cutting its losses and backing out (perhaps JBs don’t do “reverse”), it burrowed farther in, grabbing the inside of Mike’s ear canal with its bristly tarsi, heading for the eardrum and the gray matter beyond. Painful? Oh, you betcha! The folks in the ER (who were, initially, skeptics because the beetle was so far down the ear canal that they could not actually see it!) probably dined out on that story for months.

Just when you thought it was safe…

The BugLady