Howdy, BugFans,

Mike and Jessica were chasing a glow-in-the-dark Frisbee around the lawn one recent night (they live well beyond the streetlights), when they realized that they weren’t alone. There were small, luminous spots in the grass that, when they looked closer, turned out to be grub-like insects (good spotting, folks!). They carefully picked some up, made a terrarium for them, and sent some pictures to the UWM Field Station, accompanied by a gracious invitation to see the “worms” in person. The BugLady visited; she, Mike, Jessica, bug enthusiast Marie, and another friend admired the beetles; and the BugLady’s camera celebrated the occasion by going into a brief funk.

Mike said that he has seen these Glowworm beetles (most likely Phengodes plumosa, unless they’re Phengodes fusciceps) off and on over the past 20 years or so, but there’s an unusually large crop of them this year. Many of the grubs have been found under two huge maple trees. The BugLady hasn’t found anything in her reading to suggest that there’s a specific connection to maples or to the microclimate produced by the dense shade under the trees. The GwBs’ typical habitat is listed as marshes, lawns and fields, damp soil with some leaf litter, and dirt beneath decaying logs. They are nocturnal—why produce light if the sun is out?

[metaslider id=2447]

Glowworm Beetles

Glowworm Beetles are in the glowworm beetle family Phengodidae, a New World family of about 250 species with representatives living from the southern edge of Canada all the way to Chile. Most species live south of the Rio Grande. Other common names include “glow-worms” (a name shared with larval Lightning beetles) and “railroad worms.” Many species have not been thoroughly studied, Marie, and they are tricky to raise in captivity. And, their biology and natural history embody lots of good, rich science words.

In the “Never-throw-anything-away” category, when the BugLady was looking at some pictures of Phengodid larvae on-line, she realized that she had photographed one in Dallas, in 1976, and that she still has the color slide (as a wise man once said, “You are what you can’t throw away.”). It looked like this, but this series of pictures is much better than the BugLady’s.

Adult males are smallish, “bug-eyed,” glow-in-the-dark beetles with very short wing covers (elytra) and phenomenal, bipectinate antennae (their fringes have fringes). Males sometimes come to lights at night, so the BugLady is checking her porch lights extra carefully. The larvae look like fairly typical beetle grubs, and the females look like the larvae (a condition known as larviform, neotonous, or paedomorphic—all of which mean that they retain juvenile features into adulthood). Female and larval GwBs sport “lanterns” or luminescent organs. The individual that the BugLady held was just over an inch long, but the females of some species may be twice that. Adult females are more likely than larvae to be found at the soil’s surface, and they tend to appear after a rain.

Adult females come topside to attract males. Counter-intuitively, they communicate with males via pheromones (chemical perfumes) not light, which explains the male’s lovely, sensory antennae. Eggs are laid in clusters on the ground, and the female encircles and guards them, glowing the whole time, until her death about a week later. Eggs may not glow immediately but may become luminescent before hatching (the BugLady is wondering if the egg is glowing or the soon-to-emerge larva). Larvae are active and eventually pupate in the soil. Males live only briefly and do not eat, but larvae and adult females are unapologetic carnivores, mainly attacking millipedes (and maybe a few other small invertebrates—it’s hard to come by a continuous supply of millipedes if you’re trying to raise GwBs).

Bioluminescence

OK—Bioluminescence.

Who has it? Because of their similar approach to luminosity, GwBs were originally thought to be relatives of lightning beetles (Lampyridae), but our ability to do molecular studies has disproved that. Research suggests that luminescence has been “invented” at least four times during the history of insects.

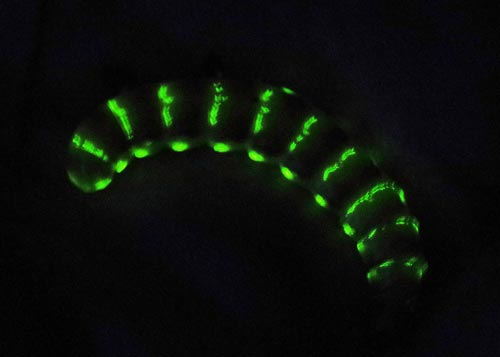

In the GwBs, the male is intentionally luminescent, a la lightning beetles; the larvae and females have paired photic organs on the sides of the segments and bands across the tops of the segments. Some species have “headlights,” and those headlights may be a different color than the sidelights, but the BugLady can’t tell from her reading if that’s universal, and more work seems to have been done on tropical species than on domestic GwBs. The side spots resemble the lighted windows of a passenger train, hence the term “railroad worm.”

How do GwBs pull it off? Their light show is produced by a chemical reaction in which an enzyme called luciferase reacts with luciferin and chemical energy is converted to light energy (History Geeks will recall that some of the original friction matches were called Lucifers). Different luciferase sequences produce different color lights (red vs green), and some species of GwBs make both. Pretty slick.

Why do they do make light? From a book called Volume 2: Morphology and Systematics (Elateroidea, Bostrichiformia, Cucujiformia partim) by Leschen, Beutel and Lawrence(2010) we learn that “The function of bioluminescence in the phengolids is not well understood. The continuous glow of the head lanterns when the larva is walking suggests an illumination function, whereas the lateral lanterns may serve a defensive function. A sudden flash might be used to dispel potential predators… The dorsolateral locations of the lanterns in a walking insect suggests that the light is to be perceived by predators above them. Aposematism (warning coloration) associated with distasteful properties is also a possible function for the lateral lantern light.” The BugLady was going to delete the two “not-in-focus” pictures of an escaping GwB included here until she realized that you can see the green side lanterns as the critter heads underground.

Can they turn the light off and on? The probable adult female we handled glowed constantly, and Marie has noticed that larvae at the bottom of the chunk of sod in the clear plastic “cage” glow, too. Leschen, et al. say that “At night, the shining head lantern can frequently pinpoint them, the lateral lanterns remaining dark. Larvae were also observed with all lanterns switched on, making it easy to detect them at great distances” (easy for them to say—the BugLady turned out not to be a good GwB spotter). A report on Phengodes fusciceps in the “Notes and News” section of the Entomological News, Volumes 17–18 (1906) states that “During the day they remained coiled and inactive; became active at night and intensely luminous; every segment, spiracle and line, apparently, showing a bead of greenish-yellow phosphorescent light. This luminosity was present in the three specimens in the same degree, but the larger specimen, for five days, showed not a ray of light. At the end of this period, it again became luminous. This would indicate the insects controlled the luminosity.”

Older BugFans have permission to hum “Glow little glowworm, glimmer, glimmer…”

To paraphrase the Bard, “O brave new world, That has such insects in’t!”

The BugLady