Howdy, BugFans,

Sources agree that the Underwings are a fascinating, frustrating, and fluctuating group of moths. There are about 200 species worldwide, some 110 of which (along with another 136 “forms” and subspecies and several large complexes)—live in the Americas, mostly in the East. The others occur in temperate Europe and Asia. The dust has not settled on their classification yet.

Underwing Moths

The genus name of the Underwings is Catocala (the accent is on the “toch”). In Ancient Greek kato meant behind or the rear/lower one and kalos meant beautiful. Rear wings beautiful. Underwings are in the huge moth family Noctuidae, the owlet moths, whose eyes glow.

As the BugLady has pointed out before, some entomologists have way too much fun naming species. The great man himself, Carl Linnaeus, began the convention of giving Underwings species names with a feminine or marital theme, and subsequent entomologists often followed his lead. Their English/Common names are translations of the genus name (C. gracelis is the Graceful Underwing; C. lacrymosa is the Tearful Underwing, etc, and the BugLady doesn’t much care for C. palaeogama, the Oldwife Underwing). There are Consort, Betrothed, Little Wife, Widow, Bride, Mother, Girlfriend and Connubial Underwings as well as Charming, Wonderful, Sordid, Dejected, Mourning, and Penitent Underwings and scores more (a few are named after people, regions or food sources).

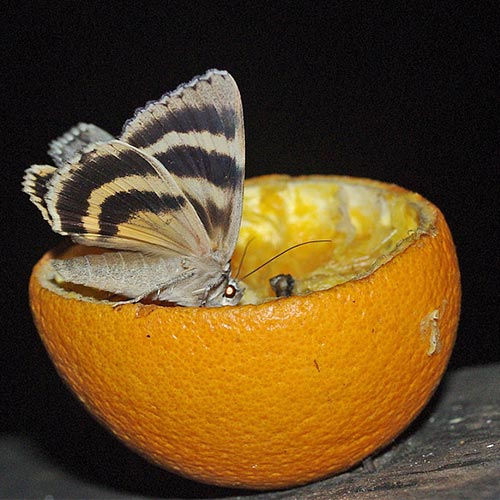

Underwings are called underwings because their very-well-camouflaged, tree-bark-patterned forewings hide a delightful surprise–multi-colored, striped hind wings. Many have black rear wings with one or two pink or orange stripes across them; some have white stripes. They show their colors when startled. The theory is that a predator will be too surprised to grab them or at least that its aim will be thrown off, and it will grab part of the wing rather than some internal organs (deflective coloration). An underwing in flight is highly visible because of its hindwings, but when it lands and suddenly conceals them, it disappears (flash coloration). Their caterpillars are cryptic, too, in shades of gray or brown, often sporting a fringe that disrupts the line where they stop and a twig starts (scroll all the way down: here).

Underwings are nocturnal (sharp-eyed BugFans may spot them on tree trunks by day, often sitting head down. Not accidentally, paler species of Underwings sit on paler trees). They’re very jumpy. He locates her via her pheromones (perfumes) at the end of summer. She lays her eggs singly or in small clutches in crevices on the bark of the host tree. The eggs overwinter and hatch in spring, just as the leaves are unfolding–fresh, tender greens for a new generation. The caterpillars are nocturnal, too. They ultimately pupate on the ground, and there’s only one generation per year.

Adult Underwings feed on nectar or sap (you can attract them—and other invertebrates—by smearing on a tree trunk a paste made of brown sugar, fermented fruit, and beer), and the BugLady sees them on the woodpeckers’ oranges at night. Their caterpillars are food specialists; most eat the leaves of willow, hickory, walnut, oak, locust, hawthorn, and poplar.

Back in 1914, Catocala moths were in the midst of a scientific debate about whether insects could hear or not. On the “Con” side were scientists who noted that the sounds of pianos, train whistles, clapping, ferry (not fairy) bells, and passing wagons elicited no response from the moths, and that when they did react, maybe it was their sense of smell that had been stimulated. On the “Pro” side, it was pointed out that many insects have auditory organs (“ears”) and sound-making structures, and why have either if you can’t hear? Researchers also noted that higher pitched sounds made by violins and fifes and whistles were noticed by the moths. The simpler sounds that got reactions, it was postulated, were mouse-like, bat-like and owl-like sounds that had “life significance” for the moths (one researcher believed that moths responded to the sound of his cyanide collecting/killing jar being uncorked, but it was shown that it was his insect net, flapping around below the moths, that was disturbing them).

Catocala moths were chosen as experimental subjects because of their habit of flying away or dropping to the ground when disturbed—unequivocal reactions to tabulate—and researchers with whistles snuck up on moths from the opposite side of the tree. The resulting, longish paper, The Auditory Powers of the Catocala Moths; an Experimental Field Study 275, but the BugLady will tell you the bottom line (Spoiler Alert!)—Yes, insects can hear.

The Underwing du jour is Catocala cara, the Darling or Bronze Underwing. The BugLady found this large (wingspread of about 3 ½ inches), chunky, dark moth at the end of August in 2011. She wasn’t sure who she was looking at, so she sent a picture off to an expert for ID—Thanks, Les. Darling Underwings can be seen in wooded areas from southern Canada and the Dakotas south to Texas, and thence east to the Atlantic.

It follows the general Underwing game plan. Adults fly during the second half of the moth season and hide by day in sheltered places (DU’s are said to like cave entrances). Clusters of eggs (red) overwinter on willow and poplar trees. When it’s time to pupate, they make a minimalist pupal case using silk and leaf litter.

The Catocala Website (below) shows a cartoon that suggests that “Some species taste better than others.” The BugLady can’t find any information to confirm or deny that.

For all things Underwing, check Bill Oehlke’s, The Catocala Website—Underwing Moths of Canada and the United States (he also has sites for sphinx moths and silk moths and a few others), and Legion of Night, and the Moth Photographers Group at mothphotographers.group.msstate.edu.

The BugLady