Note: All links leave to external sites.

Howdy, BugFans,

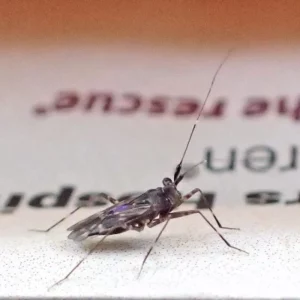

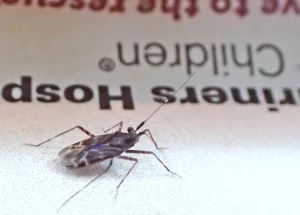

One day last August, the BugLady pulled her mail out of her mailbox and saw this little bug sitting on a newspaper, and she managed to take a few shots of it with her purse camera before it departed. She had never seen it before, but its gestalt reminded her of the (unrelated) Japanese barklice that she once encountered in southern Ohio, and of the (related) Clouded plant bugs she’s photographed locally. If BOTW had an “Obscure (but Cute) Insects” category (and many BugFans might argue that it already does), this bug would be right at home there.

When she is researching these anonymous insects, the BugLady starts with the species, and if information is thin on the ground, she backs up to genus, and then maybe backs up even farther, to tribe or subfamily or family. And so it was for Cylapus tenuicornis (no common name).

So – from the top – moving from the most general to the most specific classification:

Cylapus tenuicornis is in the True Bug order Hemiptera (110,000 species known worldwide out of an estimated total of 200,000, with 2,000 in North America). Hemipterans have piercing-sucking mouthparts that most apply to plants, but there are some carnivores and blood suckers in the bunch.

It’s in the large and diverse Plant bug/Leaf bug/Grass bug/Jumping tree bug family Miridae (11,000 known species with many more awaiting names and descriptions). Most Mirids are small (under ½”), soft-bodied, and inconspicuous, except when they are being pests of agricultural crops. Most are plant feeders – some are generalist feeders, and some target specific plants. Females use their sharp ovipositor to cut slits in plants and deposit eggs.

According to the Plant Bug Planetary Biodiversity Inventory at the University of New South Wales (the BugLady sometimes goes far afield for information), “Many lineages are strongly myrmecomorphic [ant-shaped] although the nature of their associations with ants are still not well understood.” [one], [two],[three].

Another step down – they’re in the largely subtropical/tropical subfamily Cylapinae (500 species), which researchers seem to agree is an understudied group that’s probably due for some taxonomic wrangling. Cylapines are hard to study (or even to collect) because they mostly live in leaf litter and in bark crevices and are hard to spot and pretty speedy. Cool thing about the Cylapinae is the fact that “Bugs in this group tend to forage actively on fungus covered rotten logs in humid tropical forests.” (Wikipedia). More about that in a sec.

And down another step – there are 12 species in the genus Cylapus, but only one lives in North America. It’s a Neotropical genus (found in the New World tropics, from Central America and the Caribbean, south). They are diurnal (out and about in the daytime).

Whew! Finally!

Cylapus tenuicornis is at home in eastern North America. They’re about a fourth of an inch long, “bug-eyed,” with long antennae. Here’s what they look like when they’re not sitting on the Ozaukee Press.

One question that the BugLady always asks about her subjects is “What do they eat?” And for this, we have to go back up to the subfamily. Among the people who study the Cylapinae there’s a fair amount of discussion about their menu. Remember – these bugs are typically seen on/under bark/leaf litter and on rotting logs in association with fungi. There’s been speculation that some are predators (though long legs and antennae aren’t good adaptations for chasing prey under tree bark), but a subfamily member with the awesome name of Fulvius imbecilis has been reported as preying on the larvae of small beetles and flies and assorted other invertebrates that they find under bark and in certain fungi.

But there has long been a suspicion that some species feed on specific fungi, an unusual preference among the Hemiptera. In lab experiments, Cylapus tenuicornis probed in the crevices of the fungi and underlying bark, and nymphs of two South American species mature within fungi. Some Cylapinae were eventually seen eating fungi, but researchers investigated to make sure that the bugs were eating fungi rather than eating bugs that were eating fungi. In this case, “investigate” meant catching some of them (no mean trick) and dissecting them to see if they had fungal materials in their guts. Some did, and in amounts that indicate direct feeding.

Lots of mysteries out there! YAY!

The BugLady