Greetings, BugFans,

Another celebration of insects that are not good enough nor bad enough nor beautiful enough nor bizarre enough to have fan clubs, or common names, or even much of a biography.

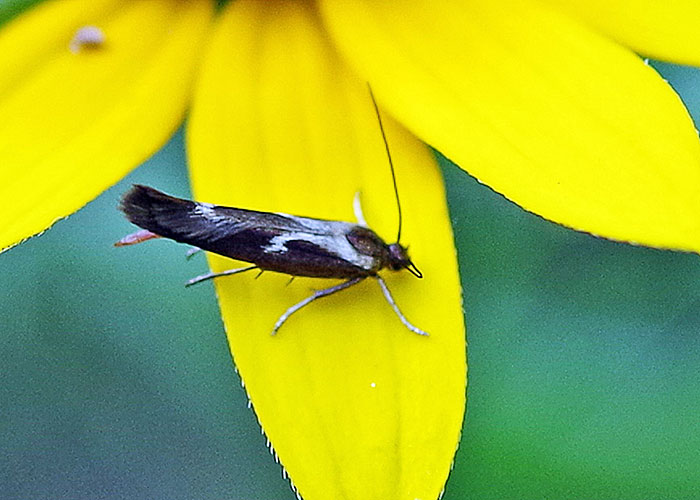

Landryia impositella

The BugLady thinks that this lovely little micromoth looks a bit skunk-ish. It’s Landryia impositella (no common name, and no explanation of its interesting species name). It’s in the Flower moth/Teardrop moth family Scythrididae, a family with only 43 species in North America. Not a lot is known about the biographies of these small, dark, moths. Their caterpillars, described in one old text as having tufts of hair growing from small warts, tend to be miners or skeletonizers of leaves of plants in the aster, goosefoot, stonecrop, and grass families. Adults are diurnal (day-flying).

Heart-leaved aster is the host of Landryia impositella’s caterpillar. It creates mines/tunnels in the leaves, one caterpillar per leaf, overwinters as a caterpillar and pupates in the next spring. Adults often nectar on yarrow flowers. The BugLady photographed this moth in mid-July.

Landryia impositella has the dubious honor of having the lowest internet profile of any insect the BugLady can recall researching—four pages of hits, some of them faux, and most others annotated checklists.

Mecaphesa Crab Spiders

As seasoned BugFans know, the BugLady is inordinately fond of crab spiders, a.k.a Flower spiders, family Thomisidae, and she thinks these Mecaphesa Crab Spiders are beauts. Crab spiders’ hunting style is described as “sedentary”—rather than build a trap web, they sit still, front pairs of legs poised, and wait for their unwary prey. They are so-named because of their shape and stance and sideways movements.

[metaslider id=8008]

Spiders in some of the crab spider genera are chunkier-looking, but the more commonly seen flower-top crab spiders, like the goldenrod crab spider, are a bit more svelte (and, of course, male crab spiders have a smaller abdomen and are “leggier” than females). Because there is a lot of variation within species, it can be hard to tell the difference between the various genera unless you look them right in the eyes (for a great visual, see http://bugguide.net/node/view/4999). Mecaphesas tend to look a bit translucent, and they have reddish bands on their legs, and some books say that spiders in the genus Mecaphesa are spinier (thanks, as always, to BugFan Mike for the ID). Some of the spiders listed Misumenops in older books are now in Mecaphesa. There are about 18 species in the genus in North America.

Mecaphesa likes to hang out in fields and grassland edges on flowers and on the tips of branches that are in bud. They are preyed upon by some species of mud dauber wasps, who stun them and stuff them into molded mud brood cells to be food for their young.

Rove Beetles

Rove Beetles (family Staphylinidae) are one of those “wait—that’s a beetle?” groups. Why? Because most beetles have a hard elytra/wing covers over the whole, or almost the whole abdomen. Elytra are actually the front pair of wings, highly modified to protect the soft flying wings underneath. The elytra of many (but not all) species of rove beetles are very short, and the flying wings that they protect must be unfolded when needed and then carefully refolded (like a road map) when not needed, a task that the beetle may use its abdomen and legs to accomplish. The exposed abdomen is somewhat susceptible to drying, so rove beetles favor humid environs, mainly on the ground, under leaves, rocks, and logs. Without full-sized elytra, the remarkably-flexible rove beetle can squeak into some pretty small spaces (without full-sized elytra, they are often mistaken for earwigs). There’s a nice overview of the family in the University of Florida’s excellent “Featured Creatures” series at http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/beetles/rove_beetles.htm. Rove beetles have graced these pages in the form of the Hairy and the Shore rove beetles.

The rove beetle du jour is in the genus Platydracus and the BugLady thinks it’s either P. zonatus or P. mysticus (she’s leaning toward the latter), beetles of woods and grasslands and the windrows of beaches. Both species feed on other insects as larvae and as adults, and they may be effective biological controls of some “problem” insects. According to one source, Platydracus mysticus may be suffering a population decline since the mid-twentieth century, possibly due to habitat change and competition with non-native rove beetles.

Spring is here—go outside—look at bugs.

The BugLady