Howdy, BugFans,

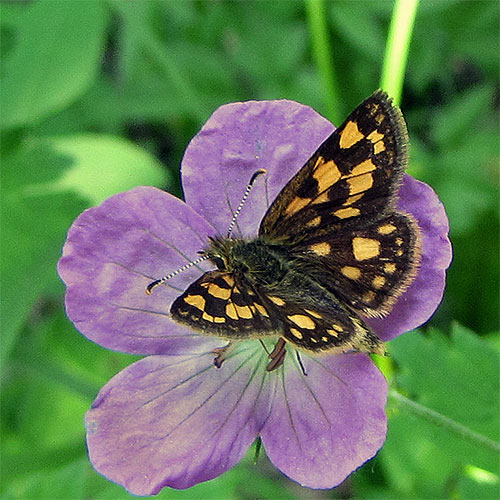

A few years ago, the BugLady wrote a BOTW episode on Skippers (family Hesperiidae) in which she lamented that Skippers seem to come in three basic models: a) small and brownish; b) small and orange-ish; and c) small and orange-and-brown. About 1/3 of North American Butterflies are skippers, and most really have to be “in the hand” in order to be identified. The lovely silver-spotted skipper, featured in that episode, breaks the mold (and who can forget the projectile frass story?). Today’s star, the Arctic Skipper, is another stand-out Skipper.

Skippers are filed in the order Lepidoptera, the Butterflies and Moths, and many entomologists perch skippers in between those two groups. Their bare, knobbed antennae lean them toward the butterfly camp; their overall hairiness/scaliness favors the moths. Some fold their wings flat over their body like moths, but others raise them vertically.

Artic Skippers

Arctic skippers (Carterocephalus palaemon) are not restricted to North America or to the Arctic. They are sub-Arctic, circumpolar/circumboreal, found in northern North America, northern and central Asia and northern Europe. Away from the U.S., the Arctic skipper is called the Checkered Skipper (well, “Chequered” in Britain). It is a threatened species in Europe and has been extirpated from England (Scottish Chequered Skippers are being relocated to the south to re-establish a population in England). In North America their range stretches from northern California across the northern tier of states and southern Canada, and through New England, wherever habitat is suitable. Suitable habitat is low, cool, damp meadows and wooded edges, glades, and trails with sun-sprinkled clearings. One reference said that they like nectar and sunshine. Adults eat nectar from wild iris, wild geranium, and some other blue flowers plus a few species of bog plants.

They are active, making lots of short flights to their nectar plants, and they may bask with their wings spread, in an un-skipper-like way. Their flight period in Wisconsin is early, starting by late May, and they are generally gone by July. Some researchers report that although they share the hours from late morning until late afternoon with other butterflies, arctic skippers have also been observed before sunrise and after sunset.

Males watch for females from perches, sometimes leaving the perch to patrol a sunny opening. When a congenial twosome meets, they launch into a courtship display, opening and closing their wings in unison. Eggs are subsequently laid on their host plants, a few varieties of grass. The caterpillars proceed to web some leaves of their food plant together, and they feed within (another reference says that they emerge at night to feed). They are full-grown by winter, which they spend as caterpillars in a hibernaculum that they construct by “silking” leaves together. They awake from their winter fast, rest for a few days without eating, pupate in a pale case, and emerge victorious five or six weeks later, in late May.

The BugLady