The mission of the Institute for Child and Family Well-Being is to improve the lives of children and families with complex challenges by implementing effective programs, conducting cutting-edge research, engaging communities, and promoting systems change.

The Institute for Child and Family Well-Being is a collaboration between Children’s Wisconsin and the Helen Bader School of Social Welfare at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The shared values and strengths of this academic-community partnership are reflected in the Institute’s three core service areas: Program Design and Implementation, Research and Evaluation, and Community Engagement and Systems Change.

In This Issue:

- Program Design and Implementation

- Research and Evaluation

- Community Engagement and Systems Change

- Recent and Upcoming Events

Program Design and Implementation

The Institute develops, implements and disseminates validated prevention and intervention strategies that are accessible in real-world settings.

Innovation and Child Neglect Prevention

By Gabriel McGaughey and Rachael Meixensperger

Families who experience stressors including housing instability, financial insecurity, or trauma, can become overloaded, leading to an increased level of need, child welfare involvement, and possible neglect. In 2020, 64% of family separations were due to neglect nationally (AFCARS Report #28, 2021), with many of its risk factor tied to issues of poverty, with a minimal number of evidence-based interventions available for communities to implement. To address this unmet need, innovative communities have been able to design high quality, evidence-informed, programs to reduce the sources of stress in families’ lives that contribute to neglect. These innovations not only provide potentially scalable solutions but can also inform how communities might approach addressing the unmet needs of families.

Neglect is a complex challenge, which often presents as a constellation of concurrent issues, that have come to a crisis point by the time a family has contact with the child welfare system. The Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) provides flexibility in funding to be used for specific evidence-based interventions in the IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse that reach ‘candidates for foster care’ to prevent separations once a family has contact with child protective services. The Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse fails to specify which interventions target neglect, but at the time of this writing, only three of one hundred and seven programs in the Clearinghouse include “economic and housing stability” as target outcomes.

To fill this gap, many organizations and communities work to support families overloaded by economic stress utilizing often limited resources to create new solutions that work within their community. Social innovation is the creation and implementation of proposed solutions that promote change. Successful innovation is context specific and requires consideration of specific characteristics of communities and community members. Different communities have specific needs and perspectives that must be accounted for to truly cultivate change. How do innovative communities support innovations to support families overloaded by stress?

Evidence Informed: Drawing on principles rooted in brain science and/or trauma informed care principles, communities strive to develop innovations that meet their specific context while still being rooted in the best available evidence. Integrating these principles into innovation, or improvement, efforts will provide a foundation for scaling successes, and advancing programs towards being evidence-based.

Co-creation: Participation of individuals and families with lived experience, or context experts, in the change process provide crucial insight into the factors that impact their communities and into what works and what does not work. Without the co-creating of solutions with context experts, content experts may enter the field with preconceived notions of community needs and solutions. While co-creation may be new, and at times feel slower than prior practices, the learning and insights present with co-creation contribute to more efficient solutions.

Resources: Prevention services get a fraction of the funding compared to child welfare, often limiting the number of resources available to support improvement and innovation efforts at scale. Operating in this scarcity environment can make taking the time for an innovation process feel like a luxury. However, scaling to pilots, or larger implementations of ideas, can be inefficient, even generating negative attitudes towards current and future change efforts from staff, stakeholders, and families. Funders can support infrastructure for innovation in prevention through targeted innovation grants, clarity and simplification of rules, training, and encouraging collaboration instead of competition. Organizational culture can provide the scaffolding for innovation by providing time, elevating shared learning as an outcome, and supporting scaling of innovation with ongoing quality improvement support.

Evaluation: The first ‘real world’ interaction most innovations have are as prototypes, small scale tests of ideas that inform if an idea may warrant eventual pilot testing. Approaches to evaluating prototypes can be different compared to quality improvement efforts with set assessment tools and metrics. The challenge for innovators is to select the prototype evaluation approach that best suits their situation and capacity. Taking evaluation approaches that fit the small scale and provide rapid feedback from participants, both those providing and receiving the service, is essential to thoughtful iteration and innovation.

Strategic learning: Learning is an outcome. Strategic learning is about deliberately gathering lessons learned in near real time to inform strategic decision making. Strategic learning serves multiple purposes, including creating institutional memory, supporting just-in-time iteration, and clarifying our hypotheses about our work. Innovators can use tools and processes from Strategic Learning to help clarify thinking, develop or refine a theory of change, and support rapid iteration.

Neglect is a prevalent wicked problem with few available options for communities to address it, requiring new evidence-informed innovations that can work in unique community contexts. At times, there is a hesitation to implement innovation due to existing struggles in current programs and the strong emphasis on the need to utilize evidence-based interventions. Evidence based interventions are important tools, however the current scope of interventions is insufficient. Innovation is all around our work, as people strive to work together to address the complex problems that overload families. By creating a clearer path to support innovation in preventing neglect, sharing lessons learned, while remaining rooted in evidence-informed principles, we create conditions to foster practices that may be the evidence-based interventions to support overloaded families of tomorrow.

Communities need more interventions to address neglect and its root causes.

Learn More:

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard

Tamarack Institute

Greater Good Studio

Here 2 There Consulting

Social Workers Who Design

Building Brains with CARE Update

Developing effective programs relies on framing learning as an outcome. One of ICFW’s longest running workshops, Building Brains with CARE, is getting the rebuild treatment this year in response to the needs of our program and community partners. Now, two different workshops will take its place. Building Brains with Relationships will focus on building communication skills rooted in evidence-based interventions such as Motivational Interviewing and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy to support executive functioning skills such as self-regulation, person-to-person. Building Brains with Community will engage community members of various personal and professional backgrounds in illuminating critical pathways to improve community well-being through program design and practice innovation, people-to-people. With great hope for the future, ICFW expects to offer each workshop in person on a quarterly basis with registration being handled on Eventbrite. Be on the lookout for these workshops in the near future.

Parenting With PRIDE Implementation

By Leah Cerwin

At Children’s Wisconsin, the ICFW partnered with Child and Family Counseling to offer our 8-week virtual group for caregivers and a child in their care: Parenting with PRIDE. This group was facilitated by mental & behavioral health clinicians in consultation with Well-Being Lead Clinician Leah Cerwin, and ICFW Master’s Level Intern Joe Moreno.

The group includes components from evidence-based Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), offering caregivers and children the opportunity to learn with one another in a supportive virtual environment, and helps parents/caregivers of younger children manage challenging behaviors such as not listening, difficulty with transitions, acting out, and handling big emotions. Parents and their children learned about strategies that promote positive behaviors, enhance parent-child relationship, and decrease undesired behaviors through engaging activities and live coaching feedback with a PCIT-trained therapist.

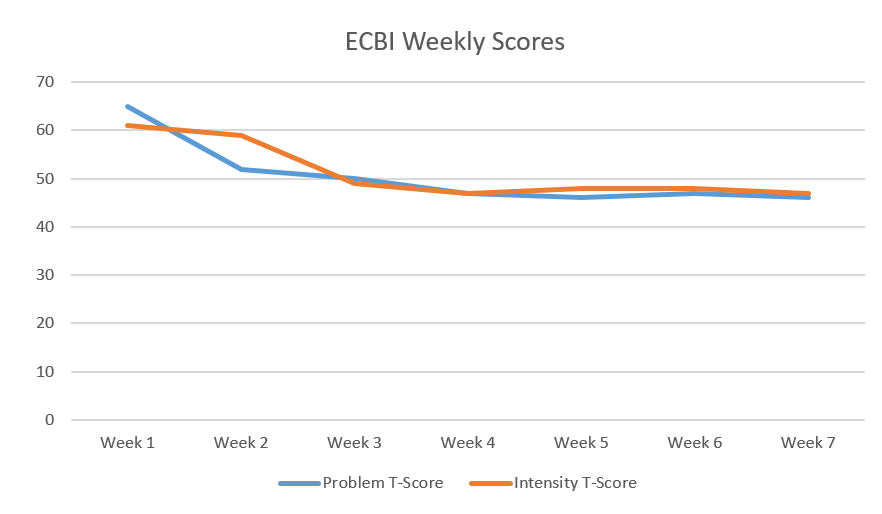

Child and Family Counseling offered two groups this summer, and both showed success in lowering externalizing behaviors in children and improving parental confidence in caregivers. Linda Chaplin, former ICFW intern and current Qualified Treatment Trainee at Children’s Wisconsin, who delivered Parenting with PRIDE to one of these cohorts shared the following progress that one family made during the eight weeks.

At intake, Mom and Dad shared that their child was having tantrums at least once or twice a day during the week, and more often on weekends. He hated being told no, and would throw things at his parents and the dog when he was angry.

Mom and Dad were excited to use the skills and both jumped right in. As shown by the ECBI scores (see chart above), their child responded right away. After our last session, Mom wrote, “We feel confident that we have the tools we need to continue to manage our child’s periodic tantrums, bedtime routine, etc. Thanks again for all the support.”

It was so rewarding to see them go from being so unsure and really questioning how to handle some challenging behaviors to feeling confident, engaged and more connected as a family.

If you are interested in learning more about the Parenting with PRIDE model or our Translational Design workshops, please contact Luke Waldo at lwaldo@chw.org.

Research and Evaluation

The Institute accelerates the process of translating knowledge into direct practices, programs and policies that promote health and well-being, and provides analytic, data management and grant-writing support.

Recent ICFW Publications

Secondary traumatic stress among home visiting professionals

Janczewski, C. E. & Mersky, J. P. (2022). Secondary traumatic stress among home visiting professionals. Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice and policy.

Working with clients with histories of trauma can put helping professionals at risk of experiencing secondary traumatic stress (STS). This study found that one in ten home visiting professionals experienced PTSD symptoms as measured by an STS assessment. Higher levels of adverse childhood experiences among professionals were associated with higher levels of trauma symptoms. Findings also suggest that staff who work in organizations with positive work environments experienced lower levels of STS. Given the association between STS and workers’ personal histories of adversity, more research is needed to understand the connection between primary and secondary exposure to traumatic events.

Community Engagement & Systems Change

The Institute develops community-university partnerships to promote systems change that increases the accessibility of evidence-based and evidence-informed practices.

Changing Course: Considering Systems Change within Social Work Practice

By Andrea Bailey and Rachael Meixensperger

Greater than reduced perceptions of social work as direct or clinical practice, the reach of this field encompasses much more than clinical practice interventions. While clinical social work is an integral component of the profession, it only represents a portion of the work being done. Dimensional in its composition, social work is most readily divided into three levels: micro, mezzo, and macro. Micro social work focuses on individuals or families while mezzo social work focuses on groups or organizations. Macro social work, sometimes referred to as systems social work, differs from micro and mezzo in that its primary focus is on large-scale change. While designating the work into these levels is helpful in defining scope and practice within each station, have these categories unintentionally created a divided practice that values micro-level interventions, while forgetting to enact change within unjust systems creating them? As professionals who abide by a code that values justice and the dignity and worth of the people we serve, to abide by our own standards of ethics we need to take action to undo these oppressive systems.

Unfortunately, the disproportionate focus on clinical social work has obscured or minimized much of the invaluable work that is being done on a macro level. Macro social work often includes community-based research, community organization, program administration, philanthropy, political advocacy, and policy practice (Iverson et al., 2019). These areas of social work target larger systems in society. Presently, many established systems uphold and sustain toxic environments which social workers must work to deconstruct. Unseen by those who are not affected by such systems, social workers have the unique opportunity to see, with unmistakable clarity, the patterns and repetitive outcomes invisible to so many. This work, inherent to the ethic of social work practice, is done to mitigate devastating systemic impacts on the lived realities of those social workers have committed to support.

Throughout our time as students, we have observed the shifting gaze, the lowering of heads, and the collective posture, when the concept of ‘macro practice social work’ is mentioned in a lecture. From the classroom to conversation amongst peers, this disengaged sentiment seems to play on repeat. Curious, we asked fellow MSW students what comes to mind when they think about macro practice within social work. Responses ranged from paperwork, to community advocacy, to quality assurance, and eventually landed on policy. The responses from our peers, while accurate in their own nebulous and disconnected way, fail to inspire connection and imagination for pathways forward that empower individuals, families, and communities, and change systems culpable of harm. So, what is needed to reimagine macro practice in a way that inspires students and social workers alike, to engage in systems change efforts?

Consider the lack of literature and social work research aimed at identifying and dismantling inequitable systems. A recent content analysis of literature focused on social work interventions at an institutional level, revealed that the majority of literature discussing social work practice focused on micro-level interventions (Corley & Young, 2018). In their research, Corley and Young (2018) implore, “Glaringly absent from these articles were calls for institutional change that challenged structural inequalities.” Likewise, consider the fractional percentage of students in academic contexts pursuing macro level practice in their careers. Social work education has, and continues to, lack adequate macro level curriculum and practice opportunities as the focus remains on clinical and direct service social work. It is necessary that social work education places an increased focus on macro level social work by increasing curriculum and practice opportunities to allow social workers to challenge systemic issues. Social work is comprised of and inhabits layers of intervention. Rather than dichotomizing macro and micro interventions, recognizing they are dynamic and integral components to the field’s overall integrity is pivotal.

As future social workers, the very ethic of our profession requires action—action to advocate, defend, support, and empower those whose care we oversee. While direct practice is essential within our field, failure to act on a macro level is passive inaction. We must exhort one another to seek change, not just in care for those harmed by toxic environments, but in the systems that are creating those environments. This is just one of many steps needed to build trust in our communities and break down strongholds of racism in social work practice. Moving forward, let us seek skilled direct practice interventions that provide the needed care for today; but even more, let us recognize our obligation to change the systems that will better tomorrow.

References:

Corley, N. A., & Young, S. M. (2018). Is Social Work Still Racist? A Content Analysis of Recent Literature. Social Work, 63(4), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swy042

Iverson, M., Dentato, M. P., Green, K., & Busch, N. (2019). The continued need for macro field internships: Support, visibility and quality matter. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(3), 478–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1671265

Strong Families, Thriving Children, Connected Communities Initiative

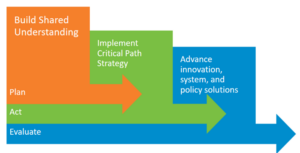

The goal of the Strong Families, Thriving Children, Connected Communities (SFTCCC) initiative is to reduce the number of family separations for reasons of neglect by building a community focused on collaboratively pursuing policies and practices that support overloaded families. SFTCCC is a developmental strategy that allows for tactics to be developed and adapted over time based on lessons learned, stakeholder feedback, and emergent opportunities. This approach can result in multiple concurrent activities across the three core phases of Building a Shared Understanding, Implementing a Critical Path Strategy, and Advancing Innovation, Systems, and Policy Solutions.

Currently, SFTCCC has been focused on Building a Shared Understanding through five Roundtables so far in 2022. These roundtables are one-hour or 90-minute long interactive sessions, that include a brief overview of the impact of stress on family functioning, small group discussions, and sharing of insights from your experience to identify challenges and develop pathways forward. Roundtables have included participants from across Children’s Community Services programs and a group of Lived Experience partners. We will be hosting an open community roundtable on September 16th from 10:00-11:30am. To keep this an interactive event, we will have limited slots, so please register here. Given that not everyone will be able to attend a roundtable, we’re also providing an opportunity to provide feedback through the SFTCCC survey, which takes the most common themes from roundtables so far and asks you to prioritize important risk factors, systemic challenges, opportunities, and contribute anything you may think is missing.

Themes from each roundtable are drafted into a report and shared with participants, and through surveys and future roundtables, will be prioritized to create the foundation for the SFTCCC’s critical pathways. Critical Pathways are specific problem/priority spaces that are focal points for elevating or designing specific and actionable system-level solutions. Developing pathways helps focus attention on the changes we want to achieve together, fosters cross systems relationships, and helps clarify shared intent. This approach provides the flexibility to connect existing efforts, invites new contributions, promotes shared learning, and roots efforts in evidence and lived experiences. This flexibility is key to building community around complex challenges that can present differently in different communities, but share root causes and impact.

SFTCCC in many ways represents an operationalizing of many of the efforts around advancing or transforming child welfare systems into a child well-being system. Core principles, such as including those with lived experience in the process, reframing how we talk about prevention, and using the best available evidence are central to SFTCCC. We believe that this initiative can uniquely contribute to the robust national dialogue by engaging providers, supporting promising practices that address root causes, and supporting innovation.

Quick links:

Register for the SFTCCC Community Roundtable here.

Complete the SFTCCC Survey here.

If you are interested in learning more, participating in a Roundtable, and/or joining this initiative, please visit the SFTCCC project page or sign up here.

Recent and Upcoming Events

The Institute provides training, consultation and technical assistance to help human service agencies implement and replicate best practices. If you are interested in training or technical assistance, please complete our speaker request form.

- SFTCCC Roundtable with Children’s Family Preservation and Support Leaders – July 20th

- SFTCCC Roundtable with Lived Experience Partners – July 29th

- Translational Design: An Introduction – August 3rd

- Innovation in Prevention Webinar Series – August 17th

- SFTCCC Roundtable with Community Partners – September 16th

- Building Brains with Community Workshop – September 21st

- ICFW Podcast Series on Overloaded Families and Neglect – September