The mission of the Institute for Child and Family Well-Being is to improve the lives of children and families with complex challenges by implementing effective programs, conducting cutting-edge research, engaging communities, and promoting systems change.

The Institute for Child and Family Well-Being is a collaboration between Children’s Wisconsin and the Helen Bader School of Social Welfare at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The shared values and strengths of this academic-community partnership are reflected in the Institute’s three core service areas: Program Design and Implementation, Research and Evaluation, and Community Engagement and Systems Change.

In This Issue

- Meet the ICFW

- Program Design and Implementation

- Research and Evaluation

- Community Engagement and Systems Change

- Recent and Upcoming Events

Meet the ICFW

We are excited to announce that Children’s Wisconsin was presented with the Key Innovator award from Economic Mobility Pathways (EMPath). Over the past few years, our ICFW team has worked closely with Jen Winkler, an ICFW Affiliate, to adapt and implement Mobility Mentoring® into Children’s Wisconsin’s child welfare program in Milwaukee. We are honored to be recognized for the collaboration and innovation that have contributed to the implementation of this promising model. Please read the award statement from the EMPath Annual Report below.

Program Design & Implementation

The Institute develops, implements and disseminates validated prevention and intervention strategies that are accessible in real-world settings.

Mobility Mentoring® in Family Support and Preservation Programs

Children thrive when they have regular interactions with responsive, caring adults. Families experiencing significant stressors related to financial insecurity, housing instability, or the impact of systemic and interpersonal trauma can be overwhelmed with stress, interrupting those interactions. To better support families overloaded by stress, Children’s Wisconsin is proud to announce a partnership through Children’s Home Society of America (CHSA) to bring EMPath’s Mobility Mentoring intervention into our Family Preservation and Support programs around the state for implementation starting in January 2022. Mobility Mentoring® focuses on using a science-based approach to support family-led goal attainment with a primary goal of economic mobility out of poverty. Children’s ICFW team members will be supporting this implementation, evaluation, and shared learning moving forward.

Learn More:

ICFW Practice Brief: Mobility Mentoring

Executive Function and Mobility Mentoring®: Using Brain Science to Promote Mobility Out of Poverty

Early adversity can derail the development and use of the core capabilities for success in adulthood. Childhood stress and trauma can have a negative impact on the developing brain. The prefrontal cortex, which controls executive functioning, and the limbic system, which controls the assessment of threats, are the most affected. When exposed to enough stress, this leads to brains that lack skills in planning and impulse control and are hypervigilant of threats. Chronic stress can also lead to a dysfunctional stress response over the lifespan. When experiencing a threat, the brain activates the “fight-or-flight” response to deal with the threat, limiting one’s ability to utilize self-regulation skills. Therefore, living in an environment of frequent fear and anxiety leads to brains that are continuously in “fight-or-flight”, affecting one’s ability to both develop and use executive function skills.

Executive function refers to the capacity to plan ahead and meet goals, control impulses, prioritize tasks, and stay focused despite distractions. These skills are developed through practice. Early childhood is an important period for developing executive function. Children who do not have the opportunity to use and strengthen these skills are less proficient and may have a difficult time managing routine tasks of life. In adulthood, executive functioning and self-regulation are the key skills necessary to get and keep a job, develop healthy relationships, and manage finances.

Growing up in poverty, even without the addition of trauma, can have a negative impact on the developing brain and executive function. Poverty is associated with chronic stress and fewer opportunities to practice executive functioning skills. Chronic scarcity, such as that experienced when living in poverty, can be viewed as a series of frequent, stressful events that can result in an overloaded brain. Constantly needing to direct attention to crises takes a toll and requires an incredible amount of energy and time. This bandwidth tax leads to poor decision making and difficulty setting realistic goals. Additionally, it can be difficult for people experiencing chronic scarcity to plan and set goals for the future because needing to frequently handle short-term crises can consume a lot of bandwidth. Executive functions, like impulse control, working memory, and mental flexibility, are important for success in work and school. This contributes to the cycle of poverty, as living in poverty itself limits one’s ability to have mobility out of poverty.

Poverty itself can impact executive functioning but considering the large overlap between living in poverty and experiencing early trauma, the cumulative impact on executive functioning is greater. This intersection of trauma and poverty is frequently seen in the populations involved in home visiting and the child welfare system. The impact can span across the life course. Childhood poverty and adversity can lead to increased parenting stress as an adult and reduce the ability to provide effective care to children. This can be associated with poor emotional regulation in children and neglect, contributing to intergenerational effects. Therefore, to implement programs that will improve the lives of child and families in this population, it is necessary to consider the impact of trauma, stress, and poverty on executive functioning.

Mobility Mentoring® is an executive functioning and trauma informed intervention that focuses on partnering with clients to build the skills, resources, and behavior to achieve financial independence. Mobility Mentoring® engages clients through a coaching model to develop decision-making and goal-setting skills in five key pillars: family stability, health and well-being, financial management, education and training, and employment and career. The intervention includes the use of external incentives to build intrinsic motivation in participants. Children’s Wisconsin is expanding the Mobility Mentoring® program to five programs in six regions in Wisconsin: Family Support (Black River Falls, Northwoods), Home Visiting (Black River Falls, Northwoods, Stevens Point, Milwaukee, Rock County), Early Head Start (Northwoods), and Education and Employment (Madison).

T-SBIRT Training and Development

T-SBIRT, or trauma screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment, is a one-session interview protocol that has been integrated into health and human service programs across Wisconsin. Implementing T-SBIRT in such settings recognizes two interrelated truths: a) most people experience significant adversity and trauma across the life course, an assertion that is all-the-more salient during this time of pandemic and collective trauma, and b) cumulative trauma exposure undermines functioning across many domains and limits engagement in various service systems.

Derived from screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for substance use, T-SBIRT has several distinct goals for participants. Namely, it was designed to:

- help participants generate insight into the extent and effects of trauma exposure,

- deepen participants’ awareness of and commitment to positive coping skills,

- enhance participants’ motivation to seek formal or informal supports, and

- strengthen participants’ engagement in current service episodes.

Thus far, T-SBIRT has been delivered by direct service providers from a variety of settings, including community-based primary care clinics, nurse home visiting programs, and employment service programs. Typically, providers conduct T-SBIRT sessions early in the course of services to strengthen rapport with service recipients, generate insight into root causes of presenting problems, and develop well-informed service and referral plans. T-SBIRT sessions extend over approximately 10 to 45 minutes, dependent on context, and evaluators have published three studies to date indicating that it is feasible to implement T-SBIRT across these diverse settings.

The primary author of T-SBIRT, Dimitri Topitzes, has led multiple T-SBIRT training initiatives in southeastern Wisconsin and other parts of the state. Typically, trainings involve one or two day intensive workshops followed by ongoing technical assistance. The workshops cover topics such as the rate and consequences of trauma exposure. He also presents the trauma service frameworks on which T-SBIRT is based, such as trauma-informed care and trauma-responsive practices. Subsequently, training participants observe T-SBIRT demonstration role-plays and complete T-SBIRT practice role-plays.

The gatherings generally end with discussions about implementation drivers and barriers along with agency-specific plans for integrating T-SBIRT within service workflows. Dr. Topitzes provides monthly T-SBIRT technical assistance or consultation during initial phases of integration to support ongoing practice. During these consultation sessions, usually held remotely, participants present T-SBIRT case examples, discuss T-SBIRT practice themes, and raise T-SBIRT-related questions.

In September of 2021, Dr. Topitzes delivered a two-day T-SBIRT training workshop to health and human service prevention specialists in Dayton, Ohio. Thirty-five direct service or administrative professionals from six area agencies attended the event, sponsored by Montgomery County Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services (ADAMHS). All agencies represented at the training received grant funding from ADAMHS, and many were planning to combine T-SBIRT with SBIRT services, a relatively common practice. According to evaluations completed by participants at the conclusion of the training workshop, participants found T-SBIRT to be very useful for their practice and were very satisfied with the training event. The participating agencies are currently completing the initial stages of implementation with the help of monthly consultation. If interested in learning more about T-SBIRT, please see the T-SBIRT Issue Brief or contact the Institute for Child and Family Well-Being.

Learn More:

ICFW Webinar – T-SBIRT: An Introduction

ICFW T-SBIRT Demonstration Video

Research and Evaluation

The Institute accelerates the process of translating knowledge into direct practices, programs and policies that promote health and well-being, and provides analytic, data management and grant-writing support.

Romain Dagenhardt, D., Mersky, J.P., Topitzes, J., Schubert, E., & Krushas, A. (2021). Assessing polyvictimization in a family justice center: Lessons learned from a demonstration project. Journal of Interpersonal Violence.

Community Engagement & Systems Change

The Institute develops community-university partnerships to promote systems change that increases the accessibility of evidence-based and evidence-informed practices.

Evaluating Systems Change at the Organizational Level

By Kelah Hatcher and Luke Waldo

“Real and equitable progress requires exceptional attention to the detailed and often mundane work of noticing what is invisible to many.” – The Water of Systems Change.

Introduction

As demand for mental and behavioral health services has grown over the past decade and is projected to outpace growth of most sectors in the coming decade, mental and behavioral health organizations face complex challenges as to how to meet the needs of children and families. At Children’s Wisconsin, we have been implementing evidence-based therapies as one potential strategy and evaluating their impact over the past four years as part of a five-year Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) grant.

The Trauma and Recovery Project (TARP) is a 5-year SAMHSA-funded initiative that aims to increase the availability and accessibility of trauma-responsive treatments for children and families in southeastern Wisconsin. Children’s Wisconsin’s Child and Family Counseling programs in southeastern Wisconsin form part of the project’s Center of Excellence (CoE), which consists of clinicians who have been trained in trauma-informed and evidence-based therapies and deliver these models to children and families. In order to demonstrate the impacts of the CoE to SAMHSA, clinicians must complete a National Outcomes Measures (NOMs) assessment at baseline, every six months, and discharge.

Presenting Challenge

During the third year of TARP, NOMs completion rates fell below 10% and the project was notified by SAMHSA that completion rates needed to improve to a benchmark of 80% or better. Clinicians face increasing and, at times, conflicting demands on their time and ability to focus on the care of their clients. By adding new assessments to their workflow, there may be a perception that their limited time with their client is being infringed upon even further. Consequently, an intense effort was made by leadership and CoE clinicians to increase completion rates. After a variety of systemic interventions, NOMs completion rates eventually reached a high of 82.1% in year four of the grant.

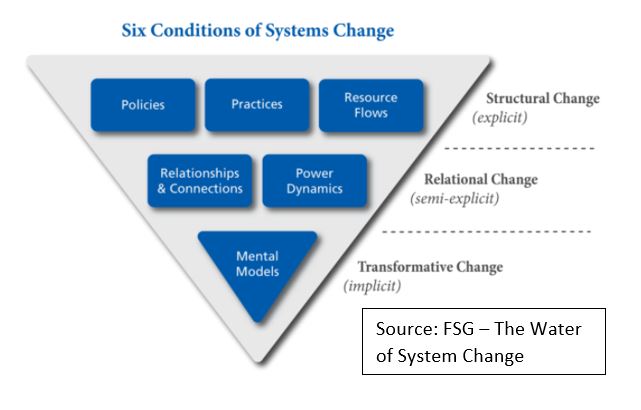

In order to learn how we addressed this challenge and improved our outcomes, we conducted interviews and surveys with grant managers, administrative staff, clinical supervisors, and CoE clinicians. We explored the six drivers of systems change to evaluate the factors involved in this process.

Six Drivers of System Change

Policies ♦ Resource Flow ♦ Relationships & Connections

According to Kania et al, policies include the “rules, regulations, and priorities that guide actions”. Resource flow is “how money, people, knowledge, information, and other assets such as infrastructure are allocated and distributed.” Relationships and connections are the “quality of connections and communication occurring among actors in the system, especially among those with differing histories and viewpoints.” Based on these conditions and feedback from clinicians, supervisors, and administrative support staff, the most significant impact on NOMs compliance was the addition of an administrative support staff member to manage the NOMs process across offices. Having an administrative staff member assigned to track compliance and offer support to clinicians centralized the process. The administrative support staff emailed the clinicians and their supervisors each month with upcoming NOMs due dates so they knew in advance what their NOMs workload would be. Each week, emails were sent to the clinicians individually reminding them what they needed to complete. The information including specific clinician, child, caregiver, and due dates made next steps very clear. The administrative support staff also entered all the NOMs into the SAMHSA database within one week of them being completed further reducing clinician burden. The policies, resource flow, and relationships and connections impacted by this change helped to improve NOMs completion by guiding actions, distributing information, centralizing core responsibilities, and ensuring quality communication.

Policies ♦ Practices

A second area that contributed to improved NOMs completion was the adaptation of tools to increase accessibility and use. This involved the organizational policies that guide actions, and practice or the “activities targeted to improving social and environmental progress; and the procedures, guidelines, or informal shared habits that comprise their work.” NOMs was initially a long, printed assessment that was filled out by hand. When COVID-19 hit, SAMHSA converted it into a six-page word document that could be completed electronically. The electronic format caused issues with clinicians not being able to type in responses and check boxes, which created another barrier to timely completion. Consequently, our team modified the assessment to make it more user friendly. This included dividing the assessment into three separate measures to use at baseline, reassessment, and discharge. Finally, clinicians were not required to enter NOMs into a database and instead were able to email them directly to the administrative support staff upon completion. These tools and increased accessibility worked to simplify processes for all staff.

Relationships & Connections ♦ Power Dynamics

Another contribution to improved NOMs completion was increasing the accountability between clinicians and their supervisors. The relationships and connections involved in this process, and the power dynamics or “the distribution of decision-making power, authority, and both formal and informal influence among individuals and organizations” were central to creating change. Regular meetings were set up with supervisors to discuss NOMs completion. These meetings were designed to support the sites with their individual issues, empower supervisors to enhance their clinicians’ NOMs completion rates, and build a community of practice to meet SAMHSA requirements.

Mental Models

Mental models are deeply held beliefs that influence our behavior and are instrumental in making transformational change. In this case study, we asked the CoE clinicians about their attitude towards assessment-based interventions to learn more about barriers to completing NOMs. All thirteen clinicians who completed the survey reported that assessment-based interventions were important in their clinical practice. Working with clinicians who value assessment-based interventions likely contributed in a positive way to the increase in NOMs completion because the clinicians understood and valued the importance of the measure.

Conclusion

Organizational and system change can be tremendously complex. We believe that we must strive for ongoing improvement, but improvement without understanding what, how and why we improved is simply not enough. Through the evaluation of our small internal system change, we were able to engage clinicians, supervisors, and administrative support staff to determine that the most influential drivers of change were new policies, resource flows, and relationships and connections. By using the six conditions of systems change, we are able to identify the many factors that impact our ability to accomplish our objectives and, ideally, replicate similar efforts in the future for sustained improvements and success.

References

Kania, J., Kramer, M., & Senge, P. (2018). The Water of Systems Change. FSG, pp. 1-18.

Learn More:

National Outcomes Measure (for children)

Recent and Upcoming Events

The Institute provides training, consultation and technical assistance to help human service agencies implement and replicate best practices. If you are interested in training or technical assistance, please complete our speaker request form.

Presentations, Trainings and Workshops:

August 2021

PCIT National Biennial Convention – ICFW presented the following panels, symposia, papers and posters:

- Creating a Community Harvest: Addressing Multifamily Needs in a Pandemic and Beyond

- The Nature of Gathering: Virtually Sowing CDI and PDI Skills and Curtailing Caregiver Stress in Group-Based Telehealth

- Unleash Your Coaching Superhero: Skills That Will Take You from a Good PCIT Therapist to a SUPER PCIT Therapist

- Irrigate Your Field of Connections: WATer-ing Collaboratively

September 2021

September 15th: Brain Science and Self-Esteem Workshop for Foster Parents

December 2021

December 1st: Mindfulness for the Family – Workshop for UWM’s Children’s Learning Center