Last spring, History graduate student Ken Bartelt stood beneath the I-794 overpass, recorder in hand, talking to former parishioners on the site where the Blessed Virgin of Pompeii Church used to sit before it became a victim of urban renewal in 1967.

“What really stood out from the interviews was the fact that the Italian community felt that they were under attack by the city of Milwaukee, and the plan to demolish the Blessed Virgin of Pompeii Church to build a highway punctuated that assault,” Bartelt said. “The church was truly the backbone of Milwaukee’s Italian community and it was a joy to see the gentlemen we interviewed recall and share those joyous parts of their lives.”

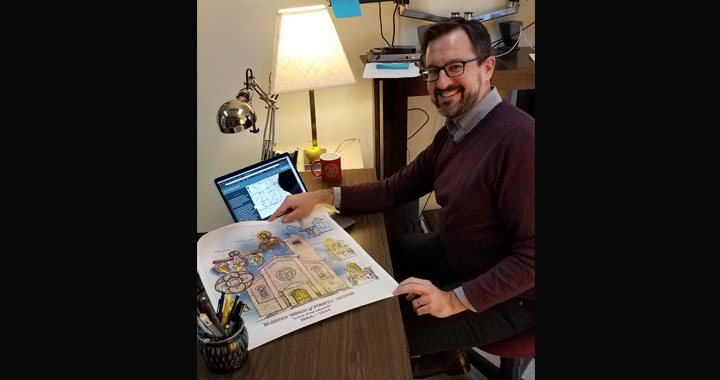

Those memories are just one of the discoveries uncovered by graduate students in UWM’s Public History program as part of assistant professor of History Christopher Cantwell’s ongoing “Gathering Places: Religion and Community in Milwaukee” project. Cantwell, who just marked his second year at UWM, teaches the program’s Research Methods in Local History class. Rather than lecture at his students, he said, he decided to show them how to research local history by pairing them up and making them do it.

And he had the perfect project in mind. Each day on his walk to campus, Cantwell passes by at least four houses of worship.

“I am a historian of religion in cities. I’ve always had a fascination with how religious communities adapt to the curiosities of the urban environment,” Cantwell said. “So I charged the students with partnering with a local house of worship and working with them to write their history.”

So far, Cantwell’s students have investigated Plymouth Church, the Chinese Christian Church, Epikos Church, Calvary Presbyterian, Congregation Emanu-El B’Ne Jeshurun, St. Casimir Roman Catholic Church, and Blessed Virgin of Pompeii Catholic Church.

All of the research is compiled on a website that includes an interactive map, timelines, recorded interviews with church members, old photographs, and more.

While they record the usual dates, prominent figures, and stories, Cantwell also tasked his students with studying each house of worship’s “lived religion.”

“[They’re] looking at religion as to how it’s practiced, rather than as what a minister might say. If they pay attention, that should unveil some surprising things,” Cantwell said.

For example, St. Casimir is one of the oldest Polish Catholic churches in Milwaukee, but it’s been folded into another parish due to dwindling attendance – except when it comes to the popular parish festival, which is held each year at the historic Falcon Bowl.

“You wouldn’t think about writing about a bowling league would be part of religion, but that is just as much as part of religion as a Sunday Mass for that community,” Cantwell said.

In addition to visiting community events and interviewing members of each congregation, the students had to do some old-fashioned legwork to track down church records.

“We spent multiple days in the Milwaukee County Historical Society archives looking at old photographs, maps, and even correspondence between city officials and a group of church members that organized to try to save the church from demolition,” Bartelt said.

Then too, students are challenged to place each congregation’s story within the greater arc of American history. The Polish congregation of St. Casimir, for example, is a direct reflection of shifting immigration patterns in the 1800s as more Eastern Europeans began striking out for America.

“They’re able to situate these histories within immigration, within urban renewal, within white flight,” Cantwell said.

The education has been invaluable for Bartelt and his classmates.

“I have a greater understanding of what an incredibly rich resource the stories of everyday people can be,” he said. “Everyone was impacted by the events of history in unique ways, and this class allowed me to sit down and hear some stories that my partner and I were privileged enough to get to share with more people through our class project.”

It’s important to compile these stories in one place because the history of its religious institutions is integral to the history of Milwaukee, Cantwell said. And he’s only getting started.

“Every time I teach this class, we’ll have new material to engage with and new stories to tell,” he added. “I want this project to contribute to our ongoing understanding of the community. They’re doing interviews with people right now so that there are resources to tell these stories later on, and they’re not overlooked or forgotten.”

By Sarah Vickery, College of Letters & Science