Human service providers ask clients questions to understand their backgrounds, identify their strengths and needs, and build rapport. Many clients have been exposed to significant adversities and traumatic events that undermine their health and well-being. Yet, service providers often have reservations about asking clients to disclose their personal histories. There are some good reasons for these concerns, but evidence suggests that they are often unfounded. This issue brief summarizes what research tells us about asking sensitive questions.

Concerns About Asking

There are several reasons why service providers may express reservations about asking their clients to disclose personal and sensitive information, including:

Will it harm my client?

Some providers may worry that asking questions about adversity and trauma could cause distress or discomfort by prompting clients to relive past experiences.

Will it hinder our relationship?

Providers could be concerned that the client may interpret the questions as intrusive or judgmental. As a result, client-worker rapport might be disrupted or damaged, which could lead to avoidance behaviors or even program dropout.

So what?

Some providers may be aware that they lack the time, training, or resources required to meet the complex needs of clients with histories of adversity and trauma. Others may feel that they can’t change the past, and that they should focus on their clients’ current circumstances and goals.

What We Know About Asking Sensitive Questions

All of these concerns are understandable. Helping professionals are committed to avoiding harm and promoting well-being. In order to do so, they need to establish and maintain healthy working relationships with their clients.

Yet there is little evidence to suggest that asking questions about adversity and trauma is harmful to clients or detrimental to client-worker rapport. In fact, based on a substantial body of research, we have learned that:

- Major adverse reactions to sensitive questions are less common than many professionals anticipate.1,2

- The vast majority of clients can respond to sensitive questions without significant distress.3,4

- Clients with a trauma history are more likely than clients without a trauma history to report discomfort with sensitive questions. However, clients with a trauma history also appear to be more likely to report that it is helpful to be asked these kinds of questions.4,5

- Clients who report discomfort with sensitive questions often say it is important to ask these kinds of questions, either because it is a valuable experience for them or because they can help others by sharing their experiences.6

- Some discomfort with sensitive questions is normative and even potentially therapeutic.7

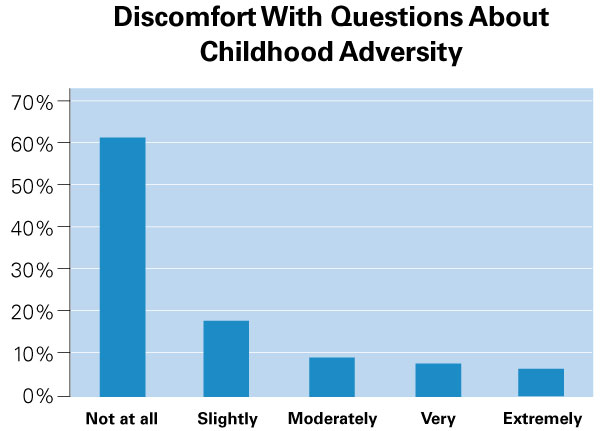

Out of more than 1,200 women that have completed the Childhood Experiences Survey, nearly 80% reported no discomfort or only slight discomfort with the questions.

New Research Findings

Data collected from Wisconsin’s Family Foundations Home Visiting (FFHV) program reinforces these conclusions. Since 2014, FFHV programs have used the Childhood Experiences Survey (CES) to ask their clients about their history of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). A final item in the CES asks clients how uncomfortable they felt answering questions about ACEs. As the figure (page 2) shows, out of more than 1,200 women that have completed the CES, nearly 80% reported no discomfort or only slight discomfort with the questions. About 10% felt very or extremely uncomfortable.

It is also likely that clients are experiencing some discomfort when they refuse to answer a sensitive question. Overall, rates of refusal on CES questions are very low (1.4%). Clients were more likely to refuse to answer a question about their sexual abuse history (5%) than any other item (1-2%), which is not surprising given the very personal nature of the subject. Refusal rates varied across FFHV programs statewide. In some agencies, no clients refused any CES item, while in other agencies the refusal rates were up to 5%. This suggests that client perceptions of sensitive questions may be influenced by the professionals who ask the questions. We also found statistically significant differences in refusal rates by client race and ethnicity, with higher refusal rates among American Indian (2.4%) and African American women (1.8%) than among Latina (1.1%) and Caucasian women (0.8%). Thus, perceptions of sensitive questions also may vary by client demographic group and cultural context.

Practice Implications

Safety first.

Client discomfort with sensitive material can be mitigated by professionals who are able to establish a safe and supportive environment. In this regard, home visiting can be an optimal context for asking sensitive questions. A skilled home visiting professional is able to develop a strong relationship with clients built on respect, trust, and unconditional positive regard.

Discomfort is a two-way street.

Professionals can influence a client’s level of discomfort with sensitive questions depending on when, where, and how they ask the questions. Professionals need to monitor their approach to sensitive topics and reactions to client disclosure.

“We may underestimate resilience. Out of concern and empathy for their clients, human service professionals may actually overemphasize survivors’ vulnerability by avoiding their traumatic histories.”

Discomfort is not necessarily a bad sign.

In fact, it is possible that “a moderate level of activation is often a good sign, indicating that the client is not in a highly avoidant or numbed state.”8

We may underestimate resilience.

Out of concern and empathy for their clients, human service professionals may actually overemphasize survivors’ vulnerability by avoiding their trauma histories.9

We may be asking the wrong question.

For professionals that serve disadvantaged and oppressed populations, adversity and trauma are nearly universal client concerns. We also know that, in the absence of appropriate support and intervention, adverse and traumatic experiences often continue to undermine health and well-being over the life course. Therefore, in addition considering what might happen if they ask clients sensitive and personal questions, professionals should consider: What happens if I don’t ask?

Recommended Approaches

Recommended approaches to administering the Childhood Experiences Survey:

- Prepare client for sensitive nature of questions.

- Clarify goals of the questions: to reducethe negative effects of exposure to early adversity.

- Set aside enough time to talk as needed.

- Don’t ask the questions too early or too late in the service term.

- Ensure privacy of the respondent at time of survey administration.

- Give client a copy of the survey.

- Record responses or ask respondent if she wants to circle responses.

- Acknowledge adversity or trauma if it has been disclosed previously.

References

1Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Arata, C., O’Brien, N., Bowers, D., & Klibert, J. (2006). Sensitive research with adolescents: Just how upsetting are self-report surveys anyway? Violence and Victims, 21, 425-444.

2Walker, E. A., Newman, E., Koss, M., & Bernstein, D. (1997). Does the study of victimization revictimize the victims? General Hospital Psychiatry, 19, 403-410.

3Black, M. C., Kresnow, M., Simon, T. R., Arias, I., & Shelley, G. (2006). Telephone survey respondents’ reactions to questions regarding interpersonal violence. Violence and Victims, 21, 445-459.

4Edwards, K. M., Kearns, M. C., Calhoun, K. S., Gidycz C. Z. (2009). College women’s reaction to sexual assault research participation: Is it distressing? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 225–234.

5Decker, S. E., Naugle, A. E., Carter-Visscher, R., Bell, K., & Seifert, A. (2011). Ethical issues in research on sensitive topics: Participants’ experiences of distress and benefit. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 6, 55-64.

6Campbell, R., & Adams, A. E. (2009). Why do rape survivors volunteer for face-to-face interviews? A meta-study of victims’ reasons for and concerns about research participation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 395-405.

7Schwerdtfeger, K. L. (2009). The appraisal of quantitative and qualitative trauma-focused research procedures among pregnant participants. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 4, 39-51.

8Briere, J. N., & Scott, C. (2014). Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment (p. 72). Sage Publications.

9Becker-Blease, K. A., & Freyd, J. J. (2006). Research participants telling the truth about their lives: the ethics of asking and not asking about abuse. American Psychologist, 61(3), 218-226.

So What?

Intended benefits of assessing and addressing childhood adversity and trauma include helping clients to:

Acknowledge exposure to adversity and trauma.

Recognize and enhance their own resilience.

Explore and alter negative effects of adversity and trauma on current functioning.

Improve personal health and well-being.

Understand potential implications for social relationships. For parents, this may focus on the need to prevent the intergenerational transmission of adversity and trauma.