Parent Child Interaction Therapy

Across home, day care, school, mental health, and social service settings, many young children present with externalizing problems such as aggression, defiance, hyperactivity, and inattention. Caregivers, teachers, and even treatment providers often struggle to manage and mitigate these behaviors.

Research shows that children exposed to adverse childhood experiences such as abuse and neglect are at a high risk of emotional and behavioral difficulties. In fact, up to 80% of children who are placed in foster care exhibit such problems.1 However, children in foster care seldom receive evidence-based mental health services,2 and effective interventions for young foster children are particularly scarce.3

Many of the most effective mental health interventions for young children center on parent training that includes live parent coaching and interactive parent-child activities.4 Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is one of the most well-validated parent training models. Drawing on attachment and social learning principles, PCIT combines play and child behavior therapies into a cohesive, structured clinical model. The immediate goals of the intervention are to help caregivers reduce parent stress, increase parent satisfaction, and strengthen behavior management skills. The ultimate goal of PCIT is to reduce child externalizing behaviors.

“Children in foster care seldom receive evidence-based mental health services, and effective interventions for young foster children are particularly scarce.”

PCIT has two phases: Child-Directed Interaction (CDI) and Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI). CDI strengthens the caregiver-child relationship by teaching parents how to reinforce wanted child behaviors and selectively ignore unwanted behaviors. PDI trains parents in positive discipline techniques, thereby improving child compliance and emotion regulation.

Evidence for PCIT

Research compiled over three decades has shown that PCIT is associated with significant and enduring impacts on externalizing problems among children ages 2-7 years.5 Emerging evidence suggests that PCIT may reduce internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression as well.6,7 In addition, PCIT has been shown to enhance parenting attitudes and skills along with parent-child interactions while reducing caregiver stress and child abuse potential.8 Studies have replicated these results with child welfare service recipients, including children in foster care.9,10

Adapting PCIT for Children in Foster Care

Despite its proven efficacy, PCIT often does not reach children in the child welfare system. To increase its availability and accessibility, Drs. Joshua Mersky and Dimitri Topitzes of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) adapted PCIT so that it can be delivered routinely within a foster care context. Drs. Mersky and Topitzes modified PCIT from a dyadic treatment averaging 12-14 weekly clinic sessions to a group-based training model consisting of 2 to 3 full-day workshop sessions. During each day-long workshop, PCIT clinicians facilitate parent skill development through instruction, modeling, role-play, and live coaching. The majority of the day’s schedule is devoted to coaching, which is an essential active ingredient of PCIT. In addition, clinicians provide PCIT phone consultation to each parent for several weeks following the first face-to-face training session. These brief phone consults are designed to enhance fidelity to the model, increase treatment dosage, and help parents apply their skills in the home environment.

This adaptation of PCIT has at least four advantages. First, whereas foster parents typically receive unproven lecture-based trainings, the PCIT model incorporates well-validated experiential and coaching strategies that promote positive parenting. Second, a group-based approach to PCIT reduces participation burden and stigma for foster parents while providing them with social learning opportunities. Third, the model follows the conventional format of foster parent training, which is typically delivered in group settings, thereby increasing the likelihood of agency uptake and sustainability. Fourth, the group-based format is designed to contain costs, again increasing the probability that resource-limited child welfare agencies will integrate it into their usual services.

Results from a Randomized Trial

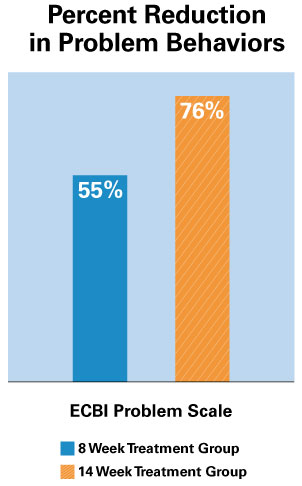

In 2014, Drs. Mersky and Topitzes completed a randomized trial of their adapted PCIT model with 129 foster families in Milwaukee. Participants were assigned to one of three study conditions: a) a wait-list control group; b) a brief intervention group receiving 2 days of PCIT training and 8 weeks of telephone consultation; and c) an extended intervention group receiving 3 days of PCIT training and 14 weeks of telephone consultation. Results revealed that the brief and extended PCIT interventions were associated with a significant decrease in parenting stress and a significant increase in positive parenting practices. In addition, children in both intervention groups exhibited significant reductions in externalizing and internalizing problems compared to the control group.11,12

Both PCIT groups improved significantly compared to services as usual.

Translating Research to Practice

Drs. Mersky and Topitzes are committed to research that increases access to innovative and effective services, especially children and families with complex needs. Reflecting this commitment, they partnered with Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin (CHW) to integrate PCIT into the child welfare system. As a leading provider of community-based services statewide, CHW is dedicated to translating research into practices and policies that promote child and family well-being. In addition to providing PCIT to foster families, the CHW Well-Being department is working with Drs. Mersky and Topitzes on implementing PCIT with biological caregivers whose children have been placed, or are at risk of being placed, in out-of-home care.

Spotlight on Project Connect

In the spirit of translating research to practice, CHW has adopted the PCIT group-based model through Project Connect. With consultation from Drs. Mersky and Topitzes, the Well-Being department has served over 40 foster families since the program was launched in the fall of 2015. Preliminary data from follow-up assessments indicate that child behavior problems generally decline following participation in Project Connect.

The sustainability and fidelity of these services are made possible, in large measure, by virtue of the strong partnership between CHW and UWM. For example, all clinicians in the Well-Being department were trained by Dr. Cheryl McNeil, an internationally renowned PCIT expert. UWM sponsored Dr. McNeil’s training events. In addition, as a Level I PCIT trainer, Dr. Toptizes provides clinical consultation through a local PCIT learning community in which all Project Connect clinicians actively participate. Dr. Topitzes also trains new CHW clinicians in the PCIT model and is preparing other PCIT clinicians at CHW to assume these supervisory and training responsibilities in the future.

References

1Keil, V., & Price, J.M. (2006). Externalizing behavior disorders in child welfare settings: Definition, prevalence, and implications for assessment and treatment. Child Youth Services Review, 28, 761-779.

2Horwitz, S. M., Hurlburt, M. S., Heneghan, A., Zhang, J., Rolls-Reutz, J., Fisher, E., . . . Stein, R. E. (2012). Mental health problems in young children investigated by US child welfare agencies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 572–581.

3Burns, B. J., Phillips, S. D., Wagner, H. R., Barth, R. P., Kolko, D. J., Campbell, Y., & Landsverk, J. (2004). Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 960–970.

4Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 567–589.

5Thomas, R., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2012). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: An evidence-based treatment for child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment, 17, 253–266.

6Brendel, K. E., & Maynard, B. R. (2014). Child–Parent Interventions for Childhood Anxiety Disorders A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 24(3), 287-295.

7Luby, J., Lenze, S., & Tillman, R. (2012). A novel early intervention for preschool depression: Findings from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 313–322.

8Thomas, R., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2012). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: An evidence-based treatment for child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment, 17, 253–266.

9Chaffin, M., Silovsky, J. F., Funderburk, B., Valle, L. A., Brestan, E. V., Balachova, T., . . . Bonner, B. L. (2004). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with physically abusive parents: Efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 500–510.

10Timmer, S. G., Urquiza, A. J., & Zebell, N. (2006). Challenging foster caregiver–maltreated child relationships: The effectiveness of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 1–19.

11Mersky, J. P., Topitzes, J., Janczewski, C. E., & McNeil, C. B. (2015). Enhancing foster parent training with Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 6(4), 591-616.

12Mersky, J. P., Topitzes, J., Grant-Savela, S. D., Brondino, M. J., & McNeil, C. B. (2016). Adapting Parent–Child Interaction Therapy to foster care: Outcomes from a randomized trial. Research on Social Work Practice 26(2), 157-167.

Hallmarks of PCIT

- Diverse learning modalities, including teaching, modeling, role-play, and coaching

- Live coaching — an essential, active ingredient

- Assessment at each session to track progress

- Individualized treatment plan based on assessment results

- Brief duration (12-14 weeks) and low cost (approximately $1,000 per client)