10 Things You Need to Know About God of Vengeance

Sholem Asch’s Got fun nekome (God of Vengeance) has one of the most remarkable histories of any modern drama. A Twitter summary of its production history would read something like this: “admired, translated, parodied, panned, banned, prosecuted, withdrawn, forgotten, revived, celebrated.” The current staging by New Yiddish Rep gives New York audiences a rare chance to hear the play in Asch’s original Yiddish. Here is an overview of the play’s rich, complex, and often tempestuous production history.

1. The Author

My great-grandfather Sholem Asch was twenty-six and a rising star of Yiddish literature’s new wave when he wrote Got fun nekome in the summer of 1906. The former yeshiva student had absorbed the latest trends in Polish, German, and Russian modernism and was now a cosmopolitan European writer. In five years, he had published dozens of short stories in Hebrew and Yiddish, and an acclaimed lyrical novella A shtetl (A Small Town). His first full-length drama, Tsurikgekumen (The Return) – later retitled Mitn shtrom (With the Current) – was produced in 1905 in Polish translation in major theatres in Cracow and Warsaw. A second play, Meshiekhs tsaytn – a kholem fun mayn folk (In the Messianic Era – A Dream of My People) was staged in Russian by Vera Komissarzhevskaya’s famous St Petersburg theatre in 1906. Asch dramatized the dreams and dilemmas of his people, bringing them to an international audience. For many Europeans, he was also the first Yiddish writer to reveal small-town Jewish life in Poland in all its variety – capturing its intense spirituality and romanticism as well as its wretchedness and poverty.

2. The Plot

Yankl Tshaptshovitsh and his wife Soreh run a brothel in the basement of their home in a typical Polish Jewish town. It’s given them a good income. But the taint of the whorehouse has thwarted their dream of finding a respectable match for their teenage daughter Rivkele. Finally, Yankl’s money has talked and the matchmaker has found a pious young groom. Yankl commissions a Torah scroll and puts it in his daughter’s room to watch over her. It’s time to close the brothel down. But will God forgive his sins and allow his daughter to live a decent life? The answer soon becomes clear as we see Rivkele sneaking downstairs into the arms of one of the prostitutes, unleashing a chain of events that brings Yankl’s dream crashing down. Sex, prostitution, lesbianism, and the desecration of a Torah scroll grabbed the headlines. But Got fun nekome is also about social and religious hypocrisy, man’s relationship with God, and parents’ dreams for their children. Plus some universally familiar types – a rebellious teenager, a domineering father, and a practical, resourceful mother.

3. The Premiere

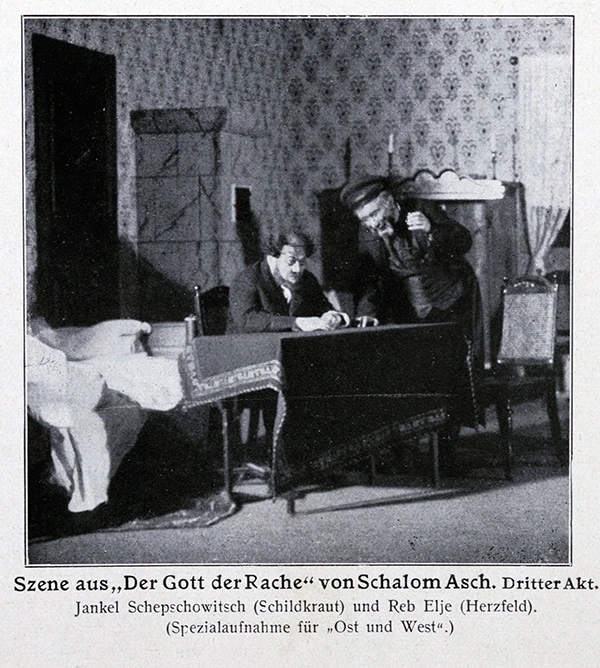

The early buzz around Got fun nekome was less about whores than herrs – Herr Reinhardt and Herr Schildkraut. The enthusiasm of these two German theatre titans for Asch’s play secured its sensational Berlin premiere at the Deutsches Theater in 1907. Director Max Reinhardt’s temple of theatrical modernism was probably the most highly-regarded theatre in Europe. Asch had seen Reinhardt’s staging of The Merchant of Venice in 1906 and had been “transported into a fairy-land” by the production and Rudolf Schildkraut’s portrayal of Shylock. Vacationing in Switzerland in the summer of 1906, Asch wrote Got fun nekome with Schildkraut in mind to play Yankl. The German-language premiere, Gott der Rache, ran in repertory from March 19th to September 8th, 1907. The director was Reinhardt’s dramaturg, Ephraim Frisch, a fluent Yiddish speaker from Stryj in Austrian Galicia who had once trained as a rabbi. Playing in repertory alongside Got fun nekome were Goethe’s The Siblings (Die Geschwister), Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and Gogol’s The Government Inspector (Revizor).

4. Early Success

Got fun nekome was the first Yiddish play to be translated and staged throughout Europe. From Berlin, Asch went straight to St. Petersburg for the Russian-language premiere. Over the next few years Asch’s “brothel play” was also translated into Polish, Hebrew, English, Italian, French, Dutch, Czech, Swedish, and Norwegian. In 1912, the Moscow branch of the cinema firm Pathé Frères released a silent film of Got fun nekome with Russian titles. According to film historian Jay Hoberman, it featured two Yiddish actors, Israel Arko and Misha Fishzon, at the head of a mainly non-Jewish cast. The film is now presumed lost. But Got fun nekomefound its greatest success on the Yiddish stage. The towering dramatic actor Dovid Kessler headed the cast of the New York Yiddish premiere, and the play was also hugely popular among the amateur Yiddish dramatic groups that flourished worldwide in the early twentieth century.

5. The Parody

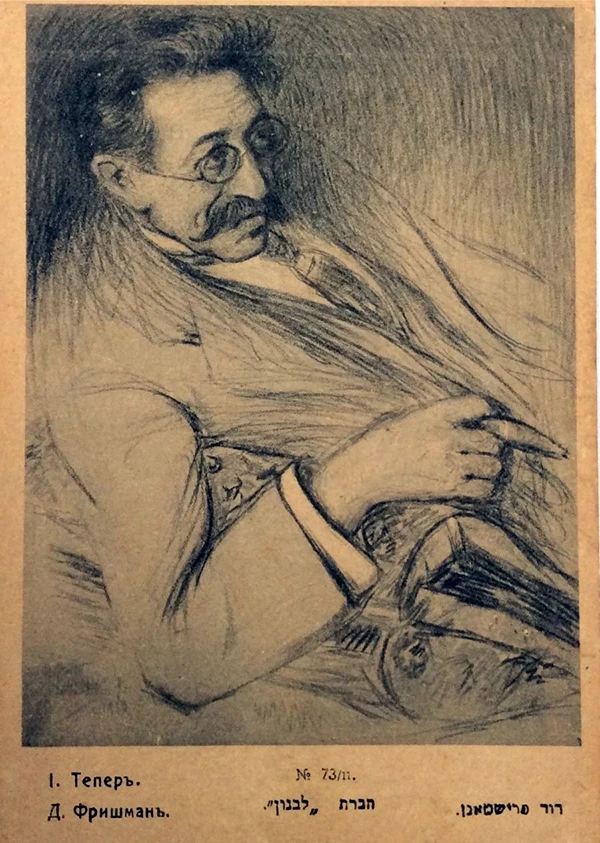

Warsaw’s Jewish writers were a rivalrous bunch and they reacted to Asch’s runaway success with about as much enthusiasm as Joseph’s biblical brothers for his fancy coat. Dovid Frishman, a renowned Hebrew and Yiddish writer, decided it was time to have some fun at the young Asch’s expense. Putting aside loftier projects, he penned a parody called God of Mercy. In Frishman’s satire, Yankl and Soreh are the parents of a dreamy, Torah-obsessed son called Ruvendl. Despairing at his lack of interest in girls, they hire an attractive young nanny to seduce him, but this only terrifies Ruvendl further and he escapes to his friends in the study-house. In place of Asch’s lesbian scene, Frishman gives us a homoerotic pastiche. “We’ll sleep in one bed every night,” Ruvendl’s yeshiva study partner entreats him. “Your father will never come near us…..will you run away with me to a faraway yeshiva?” The parody appeared in a Warsaw Yiddish theatre journal in 1908. More recently, Binyomin Weiner translated excerpts from it for Pakn treger, the magazine of the Yiddish Book Center .(It’s in the Winter 1996 issue.)

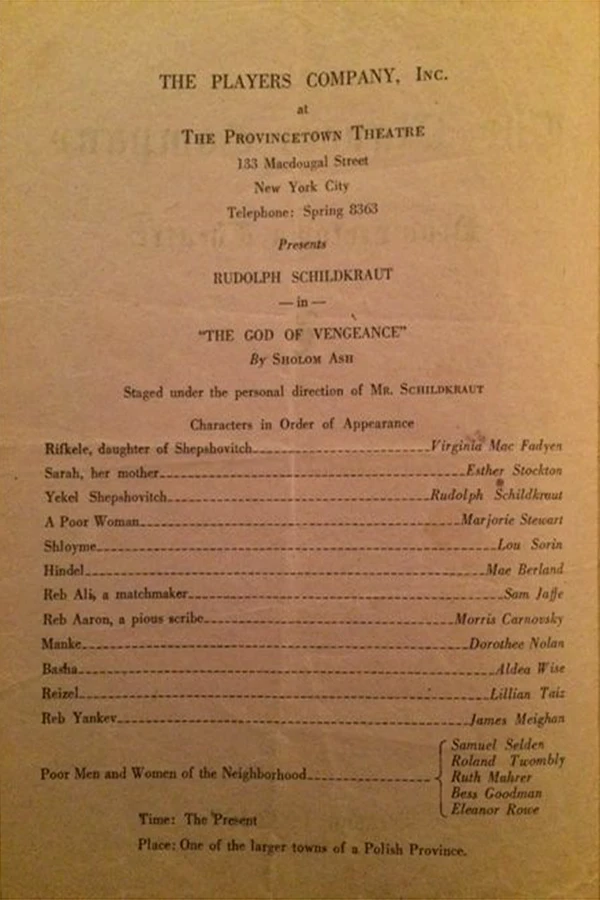

6. The Obscenity Trial

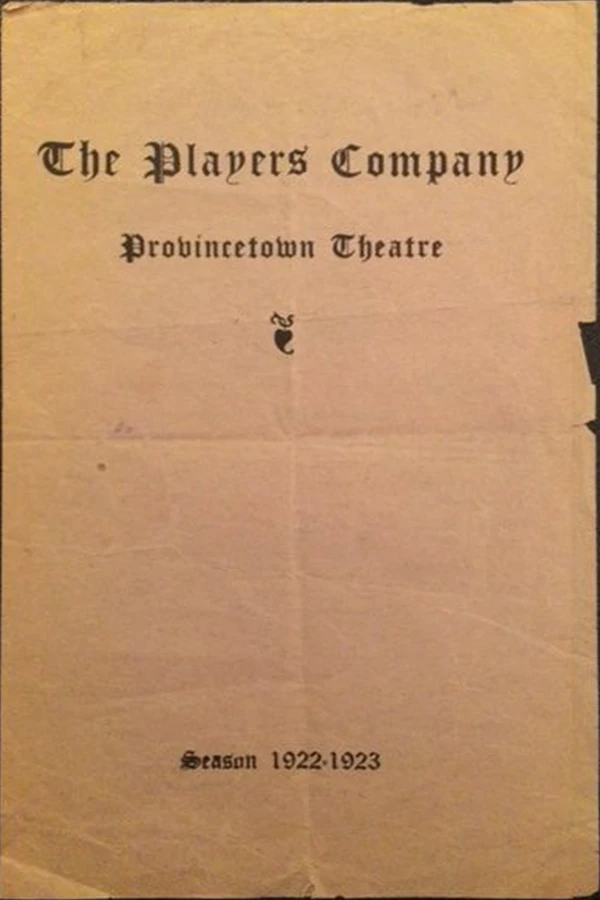

Got fun nekome on Broadway should have been Asch’s moment of triumph. Instead it turned into something of a nightmare. The English-language production opened in December 1922 at the Provincetown Theatre, moving first to the Greenwich Village Theatre and then, in February 1923, to the Apollo Theatre on 42nd Street. Schildkraut starred and directed with a stellar cast including Morris Carnovsky, Sam Jaffe, and Lillian Taiz. Urged on by influential members of the Jewish establishment, producer (and noted civil rights attorney) Harry Weinberger and the cast were arrested on March 6th and charged with “unlawfully advertising, giving, presenting, and participating in an obscene, indecent, immoral, and impure drama or play.” They pleaded not guilty. Debates about the play raged in the press, with Constantin Stanislavsky, Eugene O’Neill, Frank Crane, and Jewish Daily Forward editor Abraham Cahan all coming to Asch’s defense. The ACLU refused Weinberger’s request to help finance the appeal, but he won anyway, overturning the verdict after a two-year battle.

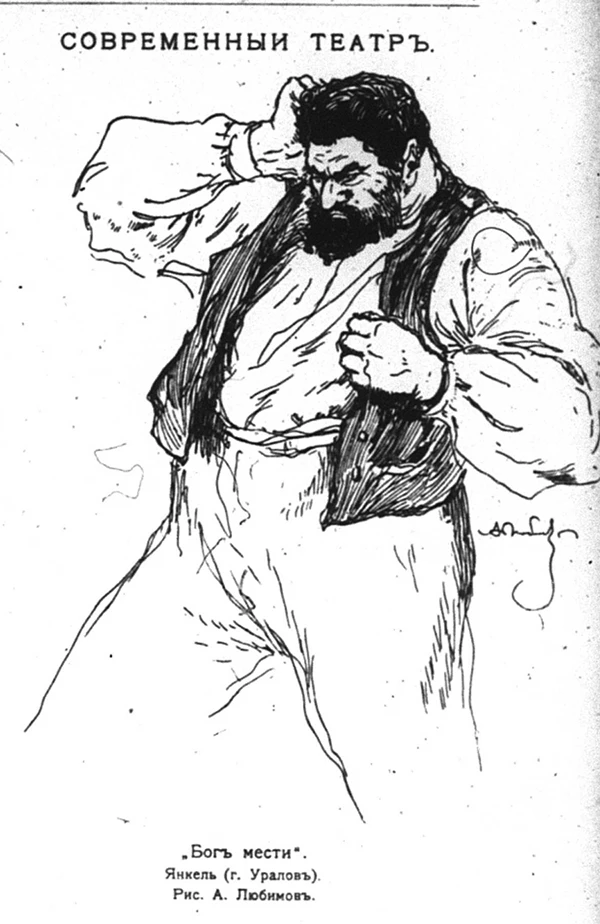

7. Actors

Asch was an enthusiastic amateur actor in his younger years, and with Got fun nekome he created some of the most intensely theatrical roles in the Yiddish repertoire. At some point in their careers, almost all the biggest Yiddish theatre stars played one or more of the main parts – Yankl the brothel-owner, Soreh his wife, their teenage daughter Rivkele and Manke the prostitute. Rudolf Schildkraut not only created the part of the father at the German-language premiere, but went on to play it in Yiddish and English over the next two decades. The acclaimed and admired Soviet actor Shloyme Mikhoels played Yankl in Moscow, as did Maurice Schwartz in America and on tour. Mark Meyerson, an actor’s actor, long ago forgotten, was renowned for his performances of Yankl in Warsaw in the 1910s. Luba Kadison and Stella Adler shared the stage as Rivkele and Manke in Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theatre production while, for the legendary Vilna Troupe, actresses Leah Noemi and Sonia Alomis played Soreh and Manke respectively. Finally, Joseph Buloff’s 1930 performance as Reb Eli the go-between was said by the New York Times critic to “make the audience gape and wriggle with a delighted astonishment that approaches ecstasy.”

8. Censorship

Got fun nekome kept the censors busy on many occasions, often with farcical results. In 1923 the celebrated Vilna Troupe came to London and a typical cat-and-mouse game ensued. The single-sheet English synopsis of “Vengeance” submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, which issued permissions for all professional theatrical performances nationwide, made no mention of a brothel. Yankl was now “the keeper of a low cabaret” with “cabaret girls” in the basement. The censor passed the play, with a strong warning about “the cabaret scene.” The Sunday Express sent a reporter along to the Pavilion Theatre, Whitechapel, and worked up a fine lather of outrage, thundering, “nothing like it has ever been staged in England.” The Lord Chamberlain shrugged (“What else could we do? No one here understands Yiddish”), and took the play off after five performances. God of Vengeance was banned one final time in London in 1946 on the advice of the Deputy Chief Rabbi, who described it as “offensive … sordid … and repulsive.” Asch himself withdrew his play that same year. Hearing of a production in rehearsal in Mexico City, he warned the company against proceeding, saying “the situation described in the play is dated and no longer exists.”

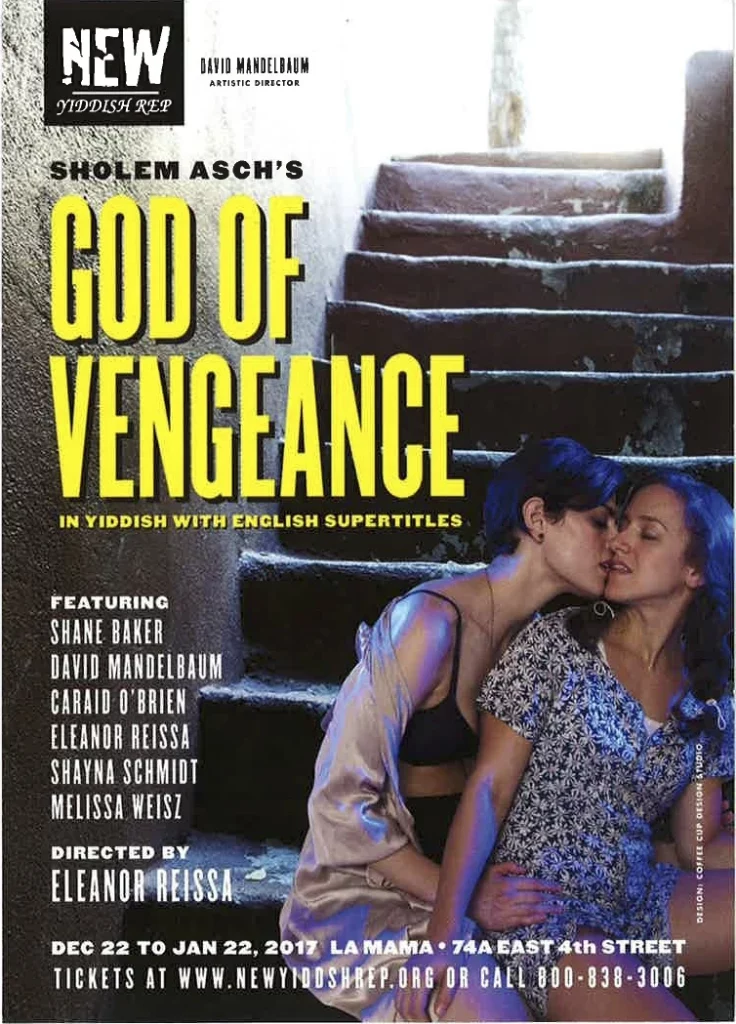

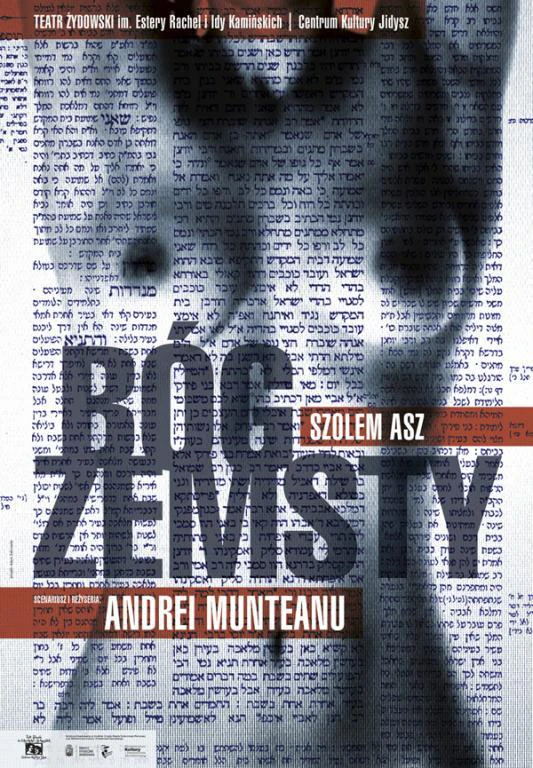

9. Revivals

In recent years, Got fun nekome – along with An-sky’s Der dibuk (The Dybbuk) – has become one of the most frequently revived plays of the modern Yiddish theatre. Among notable productions I have seen, New Yiddish Rep’s recent sell-out staging proves there is still an audience eager to hear Yiddish theatre classics in the original mame-loshn. (Even aManhattan snow blizzard couldn’t keep people away on the afternoon I went). The 1999 Todo Con Nada company’s staging, using Caraid O’Brien’s new translation, was a triumph and a revelation. The action unfolded on the go-go platform at Show World, a just-closed strip joint in a seedy labyrinth of a building in Times Square. The low-ceilinged, mirrored room made the perfect setting for Asch’s uncompromising interrogation of the motives behind the deals we make with ourselves and others. More recently, Romanian Yiddish theatre director Andrei Munteanu brought his pared-down, grotesque vision of the play to the Jewish Theatre in Warsaw. The angular wooden set resembled a scaffold as much as a house, and Munteanu’s production delivered a series of noir-like twists. Yankl’s simkhe [celebration] attracted a thieves’ parade of back-alley low life, led by a one-eyed mafia godmother in a wheelchair. And, as the play opened, the dead body of one of the girls was ritually washed, before being unceremoniously stashed under the family dining table when visitors are heard approaching the house.

10. Reworkings

Powerful dramas are like good jazz tunes – they invite creative riffs and artistic tributes. Over the last twenty years or so, Got fun nekome has been updated, revised, adapted, and reworked almost as many times as it’s been staged in the original. Pulitzer Prize winners Donald Margulies and Paula Vogel have both engaged with the play, in very different ways. Margulies’s adaptation (first seen in Seattle in 2000) sets the play on the Lower East Side in 1923, featuring a father who came to the US as a “scrawny orphan with nothing.” Paula Vogel’s Indecent uses fragments of Asch’s original in a much broader exploration of authorship, the power of theatre in general, and the lost world of Yiddish theatre in particular. In yet another recent adaptation, British writer Atar Hadari’s Merciful Father is set in postwar Manchester in a world where phone sex offers a more modern business model than prostitution. Explaining his inspiration, Hadari says, “I was living at the time in North Manchester, the biggest ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Europe, and passed a newsagent window one day where I saw a card advertising for phone sex workers. The notion of a phone sex business in the midst of this very upright neighborhood stayed with me.”

(My thanks to Barbara Henry, David Mandelbaum and Zachary Baker; to Karl Sand, archivist at the Deutsches Teater, and Tracey Felder, librarian at the Leo Baeck Institute; to my cousin Naomi Warner, and to my grandmother Ruth Shaffer who lovingly preserved what remained of her father’s pre-war archive)

Article Author(s)