Yiddish Theatre in Buenos Aires Between the Two World Wars

Since 1901, Buenos Aires has grown to be one of the most important cities for Yiddish theatre in South America. Indeed, during the first half of the twentieth century, Yiddish theatre was one of the most representative cultural practices of Argentine Jews. Some of the reasons for this are the number of Yiddish speakers, the influence that the critics held, and the public interest in the productions. For many, the theatre offered a space not only for the staging of Yiddish drama, but also for a particular type of non-religious community meeting. It was in that year, 1901, that Bernardo Waissman, the first professional actor to come to and stay in Argentina, produced Goldfaden’s “El Tartamudo” (Tsvey Kuni-Leml / The Two Kuni-Lemls) at the Teatro Doria in Buenos Aires.

Yiddish theatre in Buenos Aires was just beginning to take shape when World War I broke out, forcing many actors to return to Europe. This ushered in a period of decline. That being said, even as World War I raged, Samuel Goldenberg’s companies at the Teatro Olimpo and Samuel Blum and Carlos Guttentag’s Compañía de Operetas y Comedias (company of operettas and comedies) at the Teatro Battaglia were still able to produce two performances a week. Argentine Yiddish theatre would not rebound until 1918, but after the war, its growth would continue through the 1950s. World War II also influenced many theatre artists to settle in Argentina. What began as a Yiddish theatrical appendage in the Southern Cone, simply replicating that of other Yiddish theatre locales, would eventually take on its own unique characteristics.

Over the course of fifty years, Yiddish theatre in Buenos Aires would grow to gain relevance outside the Argentine Jewish community as well as internationally. Ultimately, Buenos Aires would become the most important place for Yiddish theatre in South America. Luminaries such as Maurice Schwartz, Ben Ami, and Molly Picon, among others, arrived regularly and were supported by local Porteño talent. The number of theatres dedicated to these works increased, and works of varied themes and styles were produced in both Yiddish and Spanish. By the end of the 1960s, Yiddish theatre’s prominence in Argentina was beginning to wane. But there is now a renewed interest in Yiddish language and culture, prompting new research on Yiddish-language artistic productions, specifically of music, theatre and literature.

We could point to factors such as the number of Yiddish speakers, critics’ influence, and a willing theatregoing public for the growth of Yiddish theatre in Buenos Aires during the first half of the twentieth century. The truth is, however, that the theatres and halls offered a space not only for the staging of works, but also for a particular type of non-religious community meeting. It constituted a social and symbolic field that accompanied and partly sheltered the processes of social, economic, cultural transformation and linguistic acquisition of the immigrants as they were blending their Eastern European roots with the customs of the new home.

Among the characteristics of Argentine Yiddish theatre, I want to mention three:

1. The influence of Tzvi Migdal, the prostitution and trafficking organization, and the struggles that the intelligentsia and politicians had in expelling them. Tzvi Migdal had a strong influence on the tenor of the theatres’ repertoires. The close relationship it had with prostitution, at least in its initial stage, has been studied by such scholars as Victor Mirelman and Nora Glickman.

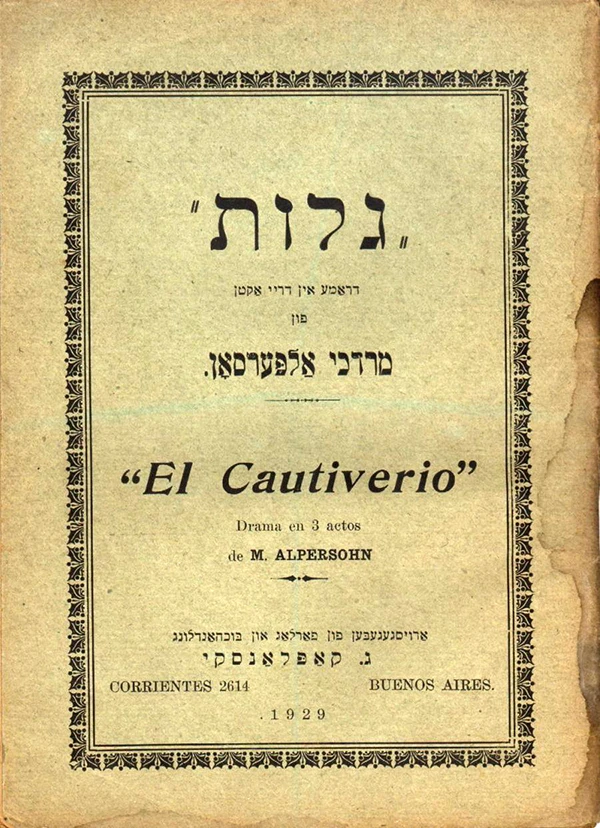

2. It took on characteristics of Criollismo, including works of Argentine authors that reflected the life in the agricultural colonies installed in the interior of the country with the support of the Jewish Colonization Association.

3. The coexistence of the “star system” (a system that granted permanent visits to “great” international figures) and the independent theatre, which had a significant impact on the non-Jewish national scene.

Thus Yiddish theatre in Buenos Aires would develop its own specific qualities. In the early 1930s, Argentina was considered one of the four major Yiddish theatre centers in the world, alongside the Soviet Union, Poland, and the United States.

This theatrical movement has been recorded in numerous testimonies. In general, the testimonies shed light on the divisions between shund theatre and art theatre, independent vs. commercial theatre, and whether or not the productions ought to be produced in Yiddish or Spanish. These commentaries also include extensive discussions of what genres and styles were taken from European and North American Yiddish theatre, and what was influenced by local genres, such as Criollismo. I will conclude by sharing fragments of three of them.

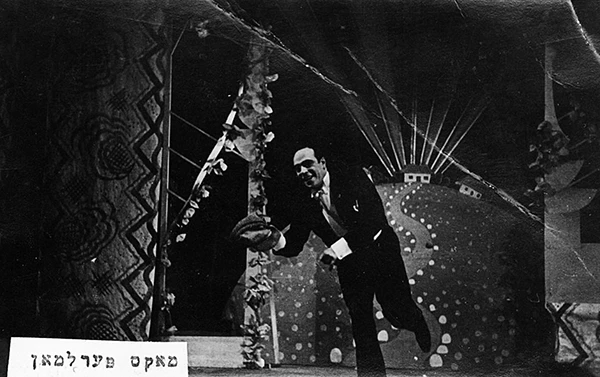

In 2001, the actor, teacher, and director Max Berliner recalled in an interview, “We arrived [in Argentina] in 1922, carrying the weight of the pogroms. Why continue suffering in Europe? We saved ourselves! My father told me to pursue theatre. I began with a poetry teacher, in Yiddish. Although there were no schools, there were seven Yiddish theatres […]

“We went to each premiere. It was a party. We dressed, we bathed. We saw the vaudeville actress Jennie Goldstein, Moyshe Oysher, and, years later, Ben Ami. The theatre was filled with prostitutes, women of the night. The theatre lived by them, they fell in love, they threw flowers, they gave away jewels. It was a mixture of real and fictional prostitution. I remember a brunette… a real beauty, who always sat in the third row. Once, at the beginning of a play featuring Jennie Goldstein, she fainted. The piece was stopped, then, after public assistance was called in, the play resumed. It really affected her.

“Then, the intellectuals and the trade unionists campaigned to demand that the impresarios bar prostitutes from entering; newspapers even stopped covering the performances. There was one activist, [Samuel] Rollansky, who was editor of Diario Israelita and director of the IWO [the Argentine branch of YIVO]. He led a campaign, posting notices that read, ‘Tmeim [pimps] are forbidden from entering.’ In 1940, at the Ombú Theater, a poster that read ‘The impure are forbidden to enter’ was posted.

“There were foreign actors who started to present works that cast immigrants in lead roles… Cooperatives were formed to rent rooms to the actors for the season. For example, they would bring in actors like Ben Ami. When ‘Jud Suß’ was produced, Samuel Goldenberg took one room, Maurice Schwartz another.”1

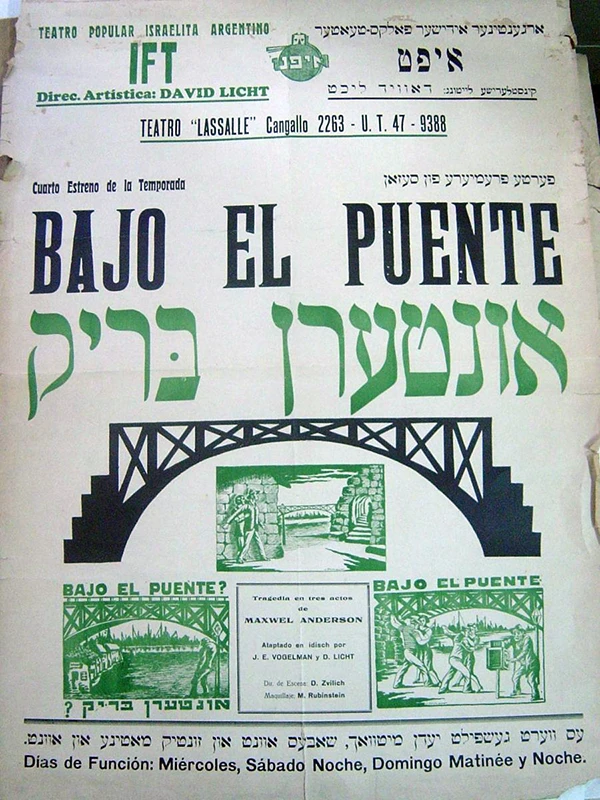

In 2006, Samuel Achum recalled in an interview, “I arrived in 1930 with absolutely nothing. I was eighteen. There was a community dining room for immigrants, and it was there that I met people from Europe. In 1932, we formed the Idishe dramatisher studio. We staged our first play a year later. The director was named Flapen. He was a hairdresser. The group grew and then we called it IFT, the Idisher folks teater, Jewish People’s Theater.”2

In an interview from 2001 with Gerardo Mazur, theatre director and Secretary of Culture for the Argentine Hebrew Society, he recalled “I went to the Yiddish theatre with my father, so I knew the seasons that brought Jacob Ben Ami and Maurice Schwartz [to Buenos Aires] and attended many of the famous IFT’s performances […] For me, Yiddish theatre in the 1930s and 40s was our community’s most important cultural display. Although I was a little boy, my father took me to many (almost 40) theatre performances during the 1930s because so many great artists visited here, from the Soleil and other theatres to the group of Jewish actors who formed the IFT, which featured David Licht [formerly of the Vilna Troupe and PYAT in Paris] as director. It was a center of impressive Jewish expression.”3

Bibliography

Nora Glickman, La trata de blancas. Estudio crítico. Buenos Aires: Editorial Pardés, 1984.

Víctor A. Mirelman, La comunidad judía contra el delito.Megamot, Revista Judía de Ciencias Sociales, 2. Buenos Aires: Milá, 1987.

Translated from Spanish by Nick Underwood.

Notes

- Interview with Berliner conducted by the author, 2001.

- Interview conducted by Lucas Fiszman, 2006.

- Interview with Gerardo Mazur conducted by the author, 2001.