“A Piquant Curiosity”: The Gender-Bending Drama Yo a man, nit a man

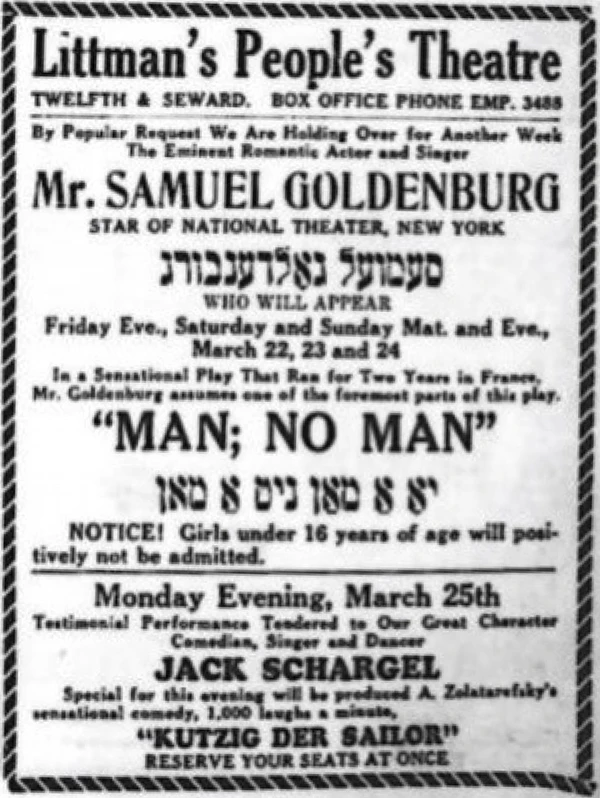

DURING THE 1920S, New York City supported as many as a dozen Yiddish theatres, but—with the exception of Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theatre—they were all entertainment venues; art was at best icing on the cake. Most of their productions were what the critics scorned as interchangeable makheraykes– contrivances penned by such productive (and now forgotten) authors as Harry Kalmanowitz and William Siegel. The Yiddish actor Samuel Goldenberg put it this way: “As for the plays that you can see during a single evening in six theatres in New York—you don’t have to sit through the entire piece. Wherever you go, all you need to do is just to stick around for half an act and you have the whole thing.”1 In a word: shund.

Goldenberg claimed that the shortage of original Yiddish literary plays compelled him to rely predominantly on melodramas for his bread-and-butter. He took a considerable amount of flak for this.2 At commercial venues such as New York’s National Theatre, where he sometimes served as the star and director during the 1920s, the “better” plays (usually translations of modern European dramas) were loss-leaders offered at midweek performances, when box-office receipts were in any case much lower than on the weekends.

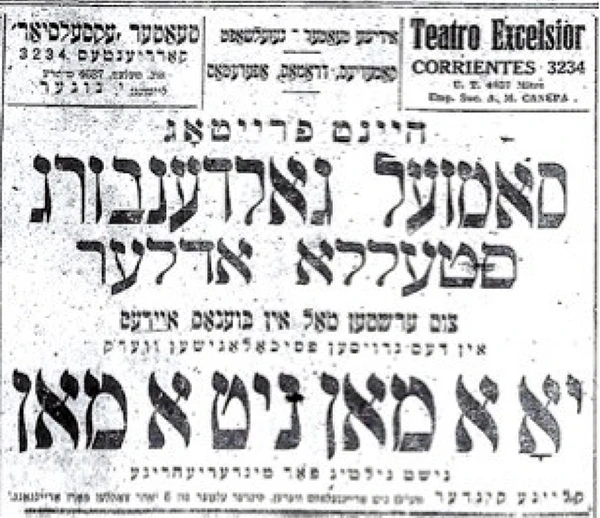

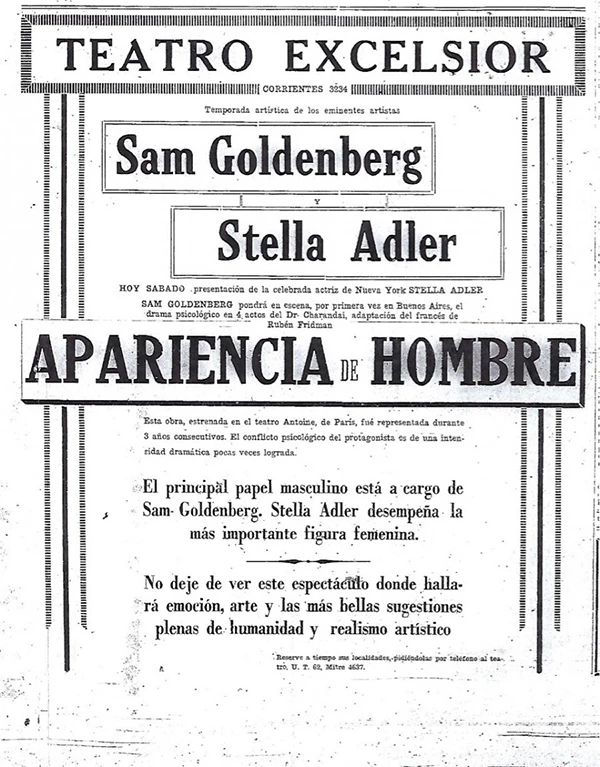

Goldenberg’s European repertory included such signature roles as Fedor Protasov in Leo Tolstoy’s The Living Corpse, Sanin in the eponymous play by Mikhail Artsybashev, and Captain Adolf in August Strindberg’s The Father. He also loved to play the rather creepy roles of Svengali, in Trilby (based on the novel by George Du Maurier), and Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde (adapted from the novella by Robert Louis Stevenson). But one of his most astonishing characters was Morris Green, in the gender-bending play Yo a man, nit a man (Yes a Man, Not a Man), attributed to an unidentified European author and freely adapted into Yiddish by the actor, director, and translator Rubin Fridman. The play was first produced at New York’s National Theatre in the fall of 1927, with Goldenberg in the role of Morris.3

Explorations of LGBTQ themes in Yiddish drama and cinema tend to be quests for the “lesbian and gay subtext,” as the web announcement for the musician and film scholar Eve Sicular’s lecture program The Celluloid Closet of Yiddish Film puts it: “From musical comedies Yidl mitn fidl (Yiddle with His Fiddle) and Amerikaner shadkhn (American Matchmaker) to classic dramas Der dibuk (The Dybbuk) and Der vilner shtot-khazn (The Vilnius City Cantor), queerness reached the screen in various guises, emerging as an alternate take on themes of conflicted identity, passing, and same-sex attachments.”

In Yo a man, nit a man, Morris Green’s predicament concerning his sexuality is what the play is all about. In it, this man who is “not a man” is referred to as a “eunuch” or a tumtum, a term that harks back to the Talmud. According to Rabbi Alfred Cohen, “A tumtum has been defined as a person with no specific male or female genitalia, a condition which is exceedingly rare.” In addition, he observes that together with a rabbinic borrowing from Greek, androgunos (“hermaphrodite—meaning one who has male as well as female characteristics”), tumtum is “often employed to describe a far more common occurrence, a person born with ambiguous genital signs.”4

If there is a need to read between the lines of Yo a man, nit a man, it is to ponder whether the playwright (or its Yiddish translator) truly intended Morris to be a tumtum in the “clinical” sense for, after all, Morris’s genitalia are never on public display to the theatre audience.5 Rather, the playwright may have had something more equivocal in mind: a character whose sexual identity could be subject to a range of interpretations on the part of Yiddish-speaking theatergoers: asexual, androgynous, impotent, castrato, “invert” (following contemporaneous understandings of homosexuality), and/or closeted gay (a later coinage). What is unambiguous about Morris, though, is that, while craving bourgeois conventionality, he is simply incapable of sexual attraction to women, something that he has been aware of since earliest childhood.

Yo a man, nit a man is in four acts6:

- Act 1 proceeds within the family circle, while Morris is still young. His brother Jack and sister Jennie sense that there is something “different” about Morris. He confides his secret—that he is undeveloped, sexually—to his father, Adolf, and his uncle, Wolf, but they are clueless and unsympathetic. Morris’s mother, Lisa, is upset by the overt manifestations of Morris’s anguish. He confesses to her that he wishes to commit suicide, but he doesn’t carry out his intentions. The act’s final scene finds the two brothers in their shared bedroom; in feverish tones Morris tells Jack about his desire for romance and his (purported) attraction to women. The act closes with Jack in deep slumber while the restless Morris weeps quietly.

- In Act 2, Morris channels his frustrations through the pursuit of money, hoping that success in this sphere might gain him the respect that he craves. He expels his uncle from the family business and indeed turns out to be a very capable businessman. Act 2 includes a squirm-worthy scene that is intended as comic relief, when Morris is introduced to the flirtatious Minna. He wards her off by claiming that he already has a girlfriend. Uncle Wolf eavesdrops on their encounter and then informs everyone that his nephew is—and is not—a man. Minna reacts by exclaiming, “Eunuch! Tumtum!” In despair, Morris again contemplates suicide, but instead decides to take another stab at bourgeois respectability. He proposes marriage to his attractive young stenographer, Beatrice, who greatly admires him for his business acumen. He has already told her about his “defect,” but she nevertheless consents to marry him.

- Act 3 portrays the couple’s married life. Morris and Beatrice attend soirées where she is besieged by men who are aware of Morris’s inability (or unwillingness) to consummate the marriage. This reinforces his feelings of shame, embarrassment, and jealousy. Morris’s vivid imagination amplifies the gossip that surrounds him. Beatrice attempts to comfort him with her caresses, but he is inconsolable. She remains faithful but is unhappy at Morris’s distress.

- The dénouement comes in the fourth and final act. Morris longs for a child of his own; maybe this will be his salvation, enabling him to begin life anew. Morris informs Beatrice that he will go away for a while and encourages her, meanwhile, to choose a sexual partner and give him a child, so as to quell the cynical mockery that surrounds him. Beatrice reluctantly acts upon Morris’s wishes, while remaining inwardly faithful to him. When he returns from his extended absence, he is nevertheless incapable of mastering his true feelings; instead, he considers the child to be tangible evidence of his personal tragedy. Finally, when Morris learns that his brother Jack (who all along was attracted to Beatrice) is the child’s biological father, he breaks down completely and finally does find his “salvation” by shooting himself.

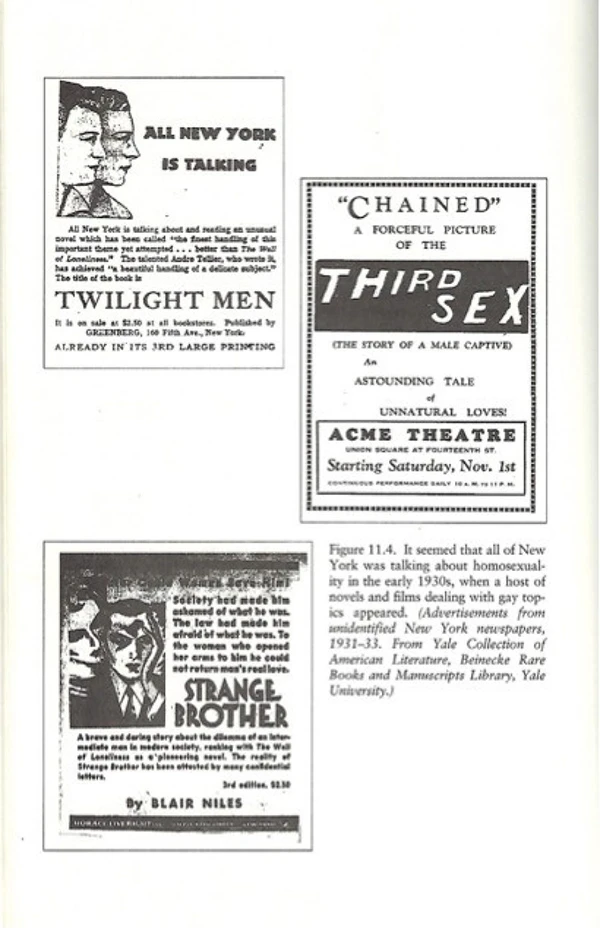

In key respects the synopsis of this play, which oscillates between drama and melodrama, is consistent with the plots of Jazz Age novels involving male protagonists who are openly identified as homosexuals. As an advertisement for one such work, Strange Brother, reads: “Society had made him ashamed of what he was. The law had made him afraid of what he was. To the woman who opened her arms to him he could not return man’s real love… A brave and daring story about the dilemma of an intermediate man in modern society.” The gay protagonists of such novels, the historian George Chauncey points out, often found their escape through suicide.7

As to the authorship of Yo a man, nit a man, it was “supposedly an ‘adaptation’ of a French author, a doctor of psychiatry and pathology,” wrote Leo Kesner in the Yidishes tageblat. Other reviews of the 1927 production indicate that Rubin Fridman was the only author who was actually named in the printed program.8 However, by the time that Goldenberg brought the play to Buenos Aires, in 1930, authorship of the French original was attributed to a mysterious Doctor Charandai—who may or may not have actually existed—and the claim was made that the French version of Yo a man, nit a man had run for three seasons at the Théâtre Antoine, in Paris—an assertion that has not yet been borne out.9

Although the true identity (or existence) of “Doctor Charandai” remains elusive, Zalmen Zylbercweig’s Leksikon fun yidishn teater does include a biographical entry for the play’s Yiddish adapter, Rubin Fridman (1885-1943). Zylbercweig writes that Fridman led a peripatetic life, beginning his theatrical career as an actor in his native city, Łódź. Prior to World War I, Fridman lived in London for six years, where he performed alongside the great actor Morris Moscovitch. In 1915, he was in Argentina—also with Moscovitch—where he undoubtedly crossed paths with Goldenberg, who led a rival troupe in Buenos Aires from 1914 to 1916. Fridman returned to Russia in 1917 and from there he moved back to Łódź and then England again (1920). At some point during the 1920s, he relocated to Belgium, where in 1929 he directed a production of An-sky’s Der dibuk. When World War II broke out, he was living in Paris; in 1943, he was murdered by the Nazis.10

Fridman translated a number of frequently performed European plays into Yiddish (though he was not always credited as the translator), including Yo a man, nit a man—which, Zylbercweig states, was a vehicle for Goldenberg. It seems plausible that Fridman proposed the play to Goldenberg, who then commissioned its Yiddish adaptation. Following its New York premiere in October 1927, Goldenberg took it on the road, performing it in many of the cities where he toured.11 Because Fridman evidently was residing in Belgium during the second half of the 1920s, the Argentine Yiddish critic Yankev Botoshanski conjectured that the original play might actually have been written in Flemish, rather than French (as claimed). In addition, Botoshanski asserted that many of the original play’s details concerning social milieu, secondary characters, and lifestyle had been stripped away by the Yiddish translator “and the play floats in the air.” In effect, it had been transformed into a star vehicle for whoever was performing the role of Morris (almost always Goldenberg), with all of the other characters—with the partial exception of Beatrice—being consigned to the shadows.

How was Yo a man, nit a man received by its audiences and by the critics? The consensus of critiques that I have seen can be summed up as follows12:

- Yo a man, nit a man straddles the boundary between drama and melodrama, without entirely falling victim to the latter tendency. It is a “piquant curiosity,” as Botoshanski put it.

- Samuel Goldenberg performed the role of Morris Green with considerable sensitivity, turning the potential mockery of the audience into sympathy for the protagonist’s personal tragedy. In Rozhanski’s words, Goldenberg was a “superb painter of the human psyche.”

Hillel Rogoff, writing in the Forward, reviewed the play about a month after its New York premiere in the autumn of 1927.13 He considered it a difficult work to pull off, given the “average” theatergoer’s “cynicism” toward people possessing Morris Green’s sexual characteristics. The actor’s challenge was to conquer the audience’s instincts toward mockery, elicit their empathy with the protagonist, and pardon his attempts to conceal his “defect.” Goldenberg succeeded in that, and “we think that this is one of the best roles that he has created,” Rogoff concluded. His fellow New York Yiddish critics concurred with this assessment, although Nathaniel Buchwald, writing in the (communist) Freiheit, scathingly dismissed the play itself, comparing it to a Coney Island “freak show.” (Other New York critics were far more generous.)

The playwright Leib Malach, in a dispatch that he sent from New York to the Argentine Yiddish daily Di prese in June 1930, dismissed Yo a man, nit a man for being a “problem play” that seemed calculated to “titillate…the broad tastes of the ‘Moishes’” in Goldenberg’s audiences.14 But, thanks to Goldenberg’s consummate dramatic skills, “strangely enough, just as with Balaam, instead of cursing, he blessed.15 Instead of the theatre—or Goldenberg himself—ruining the play, Goldenberg the actor fused it together, filled in all of the gaps, evened out and smoothed over all of the wrinkles…And Goldenberg performs the role of the tumtum with so much restraint and tact, that from the very first scene he compels the spectator to cease laughing at him as a handicapped person. Rather, one goes along with him, one empathizes, and one experiences the profound insult with which nature has humiliated him.”

In Malach’s view, very few artists could have been so effective in the role of Morris Green: “There is absolutely no doubt that were an actor other than Goldenberg to perform this play and this role, it would result in a banal, vulgar, and obscene piece.”

Goldenberg’s physical incarnation of Morris Green attracted the attentions of some observers. B. Y. Goldstein, in the (anarchist) Fraye arbeter shtime, commented on the character’s yellowish skin hue. “Goldenberg’s makeup is precisely that of a tumtum,” Yankev Botoshanski would write. “We occasionally encounter such [individuals] in the street and they distress us.” This formulation is suggestive of a point that the literary scholar Warren Hoffman has made, concerning “the epistemology of sexuality” among Yiddish-speaking Jews in the early decades of the twentieth century. “What do we know or can we know about sexuality at any given moment in history?” he asks. “While the Yiddish speaker could turn to Leviticus 18:22 for a prohibition condemning same-sex acts between men, this was not a model that spoke to the modern case of homosexual identity. How does one talk about gender and sexual identities referenced within a text for which terms do not exist?” Hoffman argues against superimposing present-day understandings about sexuality, on a “conceptual system that was not available in Yiddish” nearly a century ago.16 What was Botoshanski trying to get at?

Morris’s appearance and characterization elicited some clinically based objections on the part of a medical doctor, Paulina Rabinovitz, in an article that ran in the Buenos Aires Yiddish daily Di idishe tsaytung.17 Dr. Rabinovitz, who had attended a performance of Yo a man, nit a man at the Teatro Excelsior, wrote that from the play’s dialogue she inferred that Morris Green was a “eunuch” from birth—she also employed the Hebrew term saris (in this context, a castrato).18 She then launched into a discursus about hormones, glands, and sexual differentiation—as these were understood according to the medical science of 1930.19 Dr. Rabinovitz contended that the human male suffering from a congenital absence of testes (anorchia) exhibits physical and psychological characteristics entirely at variance with those of Morris Green, as portrayed by Goldenberg: His voice remains high, his eyes are sad, his body is bloated with fat, and his psychological development is stunted. There is no way that such an individual could possess the drive and determination that Morris Green manifested in his business career, she claimed; the physical “degeneration” of such a type is inextricably bound up with a “profound mental backwardness and absence of intellectual development.” This could all have been avoided had Goldenberg, “a talented actor,” tweaked the script so as to make Morris Green a man whose “defect” was caused by an accident or a neuro-psychological illness later in life.

The conflation, within these contemporaneous discussions of Yo a man, nit a man, of such terms as “eunuch,” tumtum, and saris, serves as a reminder of the fluid understandings, within Yiddish-speaking communities of that era, of non-normative sexual characteristics. Tumtum may have functioned in people’s minds as an umbrella term that “highlights gender instability in a way that eunuch does not and signals a different, arguably more nonspecific gender category altogether,” Warren Hoffman writes.(20) Viewed in this light, one suspects, therefore, that there was an intentional ambiguity in the playwright’s characterization of Morris’s “secret.” Thus, some of Botoshanski’s readers may have construed his offhand reference to the tumtum Morris as applying to the stereotypically effeminate gay males who (even in the 1920s) were a visible presence in certain districts of large European and American cities. Such individuals were often characterized as belonging to a “third sex”—men who were not quite men.

How familiar would these “not quite men” have been to Yiddish actors in New York City and their audiences? In Manhattan, George Chauncey notes, East Fourteenth Street between Third Avenue and Union Square—scarcely a stone’s throw from the Second Avenue Yiddish theatre district—“was one of the preeminent centers of working-class gay life and of homosexual street activity in the city from the 1890s into the 1920s.”21 He mentions a bathhouse on St. Marks Place that was frequented by heterosexual Jewish men by day and gay men at night. The Bowery, where a number of Yiddish theatres were located, was another district frequented by gay males at the beginning of the twentieth century. Thus, Morris Green may well have struck the “Moishes” as a variant of the “street types” with which they had a passing familiarity. For Samuel Goldenberg, a versatile actor specializing in unconventional roles, Morris posed an unusual and even enticing dramatic challenge.

“Degeneration”—a term that appeared in some articles about Yo a man, nit a man—was, among other things, a code word that medical practitioners (and the public at large) commonly applied to homosexual practices and homosexuality in general. Dr. Rabinovitz’s analysis of Morris’s physical attributes drew upon her understanding of the physiological ramifications of the congenital absence of the male sexual apparatus. (She was writing at a moment when homosexuality was increasingly being viewed through a scientific or clinical lens.) However, by labeling him as a “degenerate” type she also consigned him to a much larger and more visible sexual minority, the male “fairy.” It is likely within the context of the social stigma of homosexuality as a form of degeneration that Dr. Rabinovitz was suggesting that Morris’s “defect” be recast as the product of external factors, rather than inborn.

Indeed, one week beforeYo a man, nit a man was produced at the Teatro Excelsior, just such a character had been portrayed by Maurice Schwartz at a different theatre in Buenos Aires: Hinkemann, in the antiwar play by Ernst Toller that bears that same name.22 Botoshanski, in the Buenos Aires Di prese, contrasted the two plays in their reviews of Yo a man, nit a man. Hinkemann was a German military veteran whose genitals had been maimed during the Great War; his personal struggles were hitched to a larger cause, making Hinkemann a play with “an idea.” Whereas in contrast, wrote Botoshanski, Yo a man, nit a man—however daring its subject matter might seem—was at best a “milieu drama,” one deformed individual’s wail against his bitter fate. A month earlier, Leib Malach had made a similar point in the same newspaper: “Ernst Toller attempted to treat the question of a sexual handicap and its effect on the relationship between man and woman. Ernst Toller linked it to the World War, to degeneration and class, to protest against the [established] order and social injustice. The unknown author [of Yo a man, nit a man] portrayed the ‘misfortune’ within the domestic ambience of minor individuals and minor events. Consequently, the tragedy of the asexual [protagonist] is broader and more visible. Small details bring out the dramatic figure in the sharpest hues.”

Buchwald, in the New York Freiheit, was blunt: “Hinkemann is not a freak.”

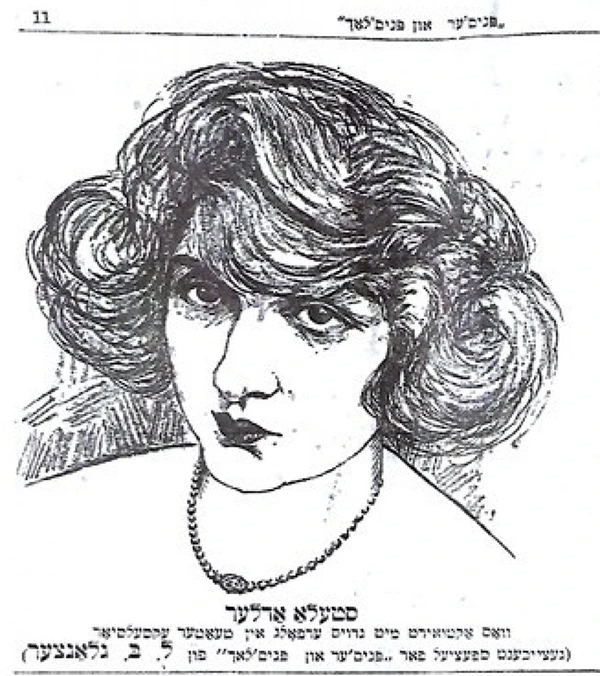

In the end and by his own choice, Morris Green’s fate hinged on his relationship with Beatrice, his wife. While Samuel Goldenberg was a constant as Morris whenever he put on the play, the role of Beatrice would have been performed by different actresses over the years. For the Buenos Aires performances of Yo a man, nit a man in 1930, Beatrice was played by none other than Stella Adler.23 Indeed, the this was her debut role before the Yiddish theatergoing public of Argentina.

Although Beatrice is a somewhat one-dimensional character, Adler—thanks to the “imprint of her pedigree” as a member of a fabled dynasty of Yiddish actors—attracted the particular attentions of the Argentine critics. They were especially struck with her imposing physical presence. “She is a tall (keyneyenehore, tall!), slender, and gracious blonde,” wrote Botoshanski. “Such figures are not to be found on our stage.” These impressions were echoed by Rozhanski, in the rival daily Di idishe tsaytung, and by the anonymous critic in the Spanish-language weekly Mundo israelita—each of whom also stressed Adler’s “elegance.” As for her acting, the Argentine critics were in agreement that she was a major talent, though they also criticized the occasionally shrill tone of her delivery. Here and elsewhere, Rozhanski drew readers’ attentions to the English intonations in her Yiddish. Botoshanski considered Beatrice to be a thankless role, but he singled out Adler for praise in the scene in Act 3 where she silently caresses her despairing husband.

By the time that Goldenberg brought Yo a man, nit a man to Warsaw, in 1934, its moment had evidently passed. Nakhmen Mayzel, writing in Literarishe bleter, offered a scathing assessment of the repertory that Goldenberg was performing in Poland: “So, now he is producing an adaptation of a French comedy, Yo a man, nit a man, and once again we see before us a great actor, with great dramatic possibilities, but this is not what we need and can demand from an actor with such a worldwide reputation as Goldenberg. We go to the theatre and want to see a play that will completely interest and stimulate us—and here we have old, second-rate melodramatic material. All of the shining moments that Samuel Goldenberg provides in these… plays aroused a longing for the Goldenberg who performed great roles in great plays.”24

Even the most demanding of the earlier critics had at least credited Goldenberg with boldness and courage in mounting a drama about this character who was struggling so painfully with the gossip and mockery surrounding his ambiguous sexuality. A psychological “problem play” set in a bourgeois family milieu simply did not speak to the concerns of Mayzel, a leading figure of the Polish Yiddish intelligentsia of the mid-1930s.

Yiddish theatergoers were certainly accustomed to seeing treatments of familial and social dysfunction. Marital betrayal, intergenerational conflict, prostitution, and outright criminality were fair game for playwrights both high (Sholem Asch, in God of Vengeance) and low (Isidore Zolatarefsky, in The White Slave).25 However, a drama centering on the protagonist’s psychological struggles with his complex sexual identity was “something new” on the Yiddish stage, in the words of the Tageblat’s critic, Leo Kesner. “You could even say: It hadn’t been done here before,” he added.26 That is what made Yo a man, nit a man so daring that the theatre managers in cities as far flung as New York, Detroit, and Buenos Aires restricted admission to adults.

What motivated Samuel Goldenberg to add this unusual play to his repertory? Part of the explanation may reside in the growing visibility of gays and lesbians on the urban scene, including in clubs and speakeasies that were frequented by gay and straight customers alike. “In the Prohibition years of 1920-33, [gay males] acquired unprecedented prominence throughout [New York] city, occupying a central place in its culture,” George Chauncey writes, “[t]hey became the subject of newspaper headlines, Broadway dramas, films, and novels.”27 It is possible that Goldenberg was aware of the gay-themed plays that were being produced on some Broadway stages during the mid-1920s. In a bid to capture the Zeitgeist, he may have desired to bring something in this vein to Second Avenue audiences. Vi es kristlt zikh, azoy yidlt zikh, as the expression goes.

Why, then, did Yo a man, nit a man nevertheless take a somewhat oblique approach to its protagonist’s inner conflicts over his sexuality? Why wasn’t Morris Green presented more forthrightly as a gay male, albeit one who concealed his sexual identity? On the one hand, Warren Hoffman asserts, “the Yiddish community” of the 1920s and 1930s was “one that did not rigorously engage with homosexual identity.”28 By this reading, the closeted gay male would have been an alien type to the Yiddish theatergoer, whereas a tumtum—however that term might be defined—would have represented a somewhat familiar concept. As Leo Kesner put it, “This is not a treyf dish—just a little strange and awkward.”29

Apart from that, by the time that Yo a man, nit a man had its New York premiere in October 1927, there was an enhanced degree of risk in producing a play with an unambiguously gay protagonist. Eight months earlier, on the evening of February 9, 1927, there were simultaneous police raids on the Broadway theatres where three gay- and lesbian-themed plays were being performed. And then, a couple of months after the police raids took place, George Chauncey notes, the New York “state legislature amended the public obscenity code to include a ban on any play ‘depicting or dealing with the subject of sex degeneracy, or sex perversion.’”30 Overtly gay characters would no longer be permitted on mainstream theatre stages. Goldenberg would certainly have known about the Broadway plays’ suppression, which made the front pages of both the English- and Yiddish-language dailies.31 Indeed, in his review of Yo a man, nit a man, Nathaniel Buchwald made an overt comparison with the themes of one of the suppressed Broadway plays, The Captive: “The interest is the same: there, lesbian love, a masculine woman with her ‘problems’; here, a tumtum, a man who is no man—with his ‘drama.’”32

Morris’s physiological challenges dovetailed with another common theme of its era. In medical literature and popular culture alike, the 1920s was the decade of “monkey glands” as a nostrum for treating impotence in males. They became a widespread motif, encountered in short stories, Broadway revues, household artifacts, and even a cocktail. There was even a one-act Yiddish play, dating from 1925, containing the lyrics to a song titled “Monkey Glands.”33 All the same, discussions of Yo a man, nit a man universally focused on a much more serious condition: Morris as tumtum, eunuch, or saris.(34)

In sum, Fridman and Goldenberg would presumably have considered it safer to couch Morris Green’s sexual dilemma as the byproduct of a congenital condition—one that served, in turn, as a stand-in for what many in the audience could have understood in a different light.35 In other words, in order to avoid prosecution, one speculates that Fridman and Goldenberg may have recast an effeminate French homosexual as a Jewish tumtum.36 Whatever the case, the Yiddish production of Yo a man, nit a man represented an earnest attempt to address its public’s anxieties about sexual representation through the lens of the popular culture of its era. Yet, in the end, this “piquant curiosity” remained an outlier—perhaps the only frequently performed Yiddish play to focus so explicitly on a character’s struggles over his complicated sexual identity.

Notes

- “Samuel Goldinburg iz nekhten gekumen keyn Buenos Ayres,” Di Idishe tsaytung (Buenos Aires), June 11, 1930.

- Goldenberg was not alone in this respect; for example, during seasons when the highly respected dramatic actress Celia Adler was not part of the cast at the Yiddish Art Theatre, she too performed in tear-jerkers at the commercial theatres.

- I first learned of this play while scrolling through microfilms of the Argentine Jewish press, as part of a research project centering on Samuel Goldenberg and the 1930 Yiddish theatre season in Buenos Aires.

- Rabbi Alfred Cohen,”Tumtum and Andrygynous,” Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society 38 (Fall 1999), 62, accessed June 17, 2019, http://www.daat.ac.il/daat/english/journal/cohen-1.htm. One Hebrew-English dictionary defines tumtum as a “person with hidden or undeveloped genitals, whose sex it is difficult to determine.” See Reuben Sivan, Edward A. Levenston, compilers, The Megiddo Modern Dictionary: Hebrew-English (Tel Aviv: Megiddo Publishing, 1965), 293.

- The congenital lack of testicles in a male is also known as anorchia. See “Congenital Absence of the Testes,” Contact: For Families with Disabled Children, accessed May 21, 2019, https://contact.org.uk/medical-information/conditions/c/congenital-absence-of-the-testes/?page=6&f=C.

- I have not located a script for Yo man, nit a man; so, I am relying primarily on the detailed plot summaries that were included in reviews of the July 1930 production in Buenos Aires. See Shmuel Rozhanski (Samuel Rollansky), “’Yo a man, nisht a man,’ oyfgefihrt durkh Samuel Goldenburg, tsum debut fun Stela Adler in teater ‘Ekselsyor’,” in Di idishe tsaytung, July 13, 1930; and Yankev Botoshanski (Jacobo Botoshansky), “S. Goldinburg un Stela Adler in a kuryoz pikanter pyese,” in Di prese, July 13, 1930. “Spoiler alert” seems to have been an alien concept to the Argentine Yiddish theatre critics.

- Blair Niles, Strange Brother (New York: Horace Liveright, 1931). The ad is reproduced in George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 326. Regarding gay-themed novels of the early 1930s, Chauncey writes: “Most ended with the death or suicide of the gay protagonist, but only a few made this end seem inevitable…” See Chauncey, Gay New York, 324. The trajectory of the play’s protagonist (minus his suicidal end) also bears comparison to that of David Levinsky, in Abraham Cahan’s 1917 novel The Rise of David Levinsky—the protagonist channels his sex drive by pursuing business success, yet is dogged by social pressures to marry; ultimately, Levinsky remains a bachelor. The parallels between the plots of Yo a man, nit a man and The Rise of David Levinsky were pointed out to me by Warren Hoffman, whose book The Passing Game: Queering Jewish American Culture (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2009) includes a chapter devoted to a queer reading of Cahan’s novel.

- L[eo] Kesner, “Di mitenvokhige pyesen,” Yidishes tageblat (New York), November 25, 1927. See also the following reviews from the New York Yiddish press: N[athaniel] Buchwald, “Eyropeyer drame oyf second evenyu,” Frayhayt (Freiheit), October 20, 1927; B. Y. Goldstein, “Oyf der teater evenyu,” Fraye arbeter shtime (Freie Arbeiter Stimme), November 25, 1927.

- This claim was made in an advertisement by the Teatro Excelsior for Apariencia de hombre (the Spanish title that the theatre management used for Yo a man, nit a man), in the Spanish-language weekly Mundo israelita (Buenos Aires), July 12, 1930. Nick Underwood has gone through advertisements for some French newspapers, but these did not yield the proof that such a play was put on in France during the 1920s. The quest continues.

- “Fridman, Rubin (Meir Rubin),” in Zalmen Zylbercweig (compiler; assisted by Jacob Mestel), Leksikon fun yidishn teater (Lexicon of the Yiddish Theatre), vol. 3 (New York: Hebrew Actors Union, 1959), cols. 2378–2379.

- To date, I have come across reviews of and ads for Goldenberg’s productions of Yo a man, nit a man in New York City (1927), Detroit (1929, where its English title was advertised as Man, Not Man), Buenos Aires (1930), and Warsaw (1934). At New York’s National Theatre it was performed in the middle of the week, when ticket sales were generally lower. The chief attraction at that theatre during the 1927-1928 season was the Siegel-Olshanetzky operetta A Night in California, starring Aaron Lebedeff and Jacob Jacobs. Lebedeff later recorded the operetta’s hit song, “I Like She.”

- What follows largely draws upon treatments in the New York Yiddish press, from 1927, and the Argentine Jewish press in both Yiddish and Spanish, from 1930.

- Hillel Rogoff, “Samuel Goldinburg in a interesante shtarke role,” Forverts, November 18, 1927.

- Leib Malach, “Samuel Goldinburg,” Di prese, June 13, 1930. Indeed, in at least one performance of the 1927 New York production, Goldenberg actually broke character and shushed the audience during the first act, when some members of the public inappropriately broke out in laughter at moments that he intended to be serious. See Goldstein, “Oyf der teater evenyu,” and Kesner, “Di mitenvokhige pyesen.”

- The biblical episode of Balaam is recounted in the Torah portion Balak (Numbers, chapters 22–24).

- Hoffman, The Passing Game, 13–14, 21.

- Dr. Paulina Rabinovitz, “A por verter fun a doktor vegen Tshardans drame ‘Yo a man nisht a man,’ un artist S. Goldenburg’s oyffihrung,” in Di idishe tsaytung, July 20, 1930.

- Like Dr. Rabinovitz, B. Y. Goldberg, in his review for Fraye arbeter shtime (“Oyf der teater evenyu”), interchangeably employs the terms sarisand tumtum to describe Morris Green’s sexual identity. Introduction of saris adds yet another layer of ambiguity (or confusion) to our understanding of the character’s complicated predicament. Drawing upon Tractate Yevamot in the Babylonian Talmud, Alana Suskin writes that the rabbis may have recognized as many as seven gender categories: male, not-male (female), androgunos (“a person who has aspects of both male and female genitalia”), tumtum (“a person whose genitals are obscured, making their gender uncertain”), aylonit (“a female who fails to produce signs of female maturity by the age of twenty”), saris (“the general term for a male who does not produce signs of maturity by the age of twenty”)—which “can further be broken down into two: a saris khama is a male who is sterile because he was born that way, and a saris adam is a male who is sterile because he was castrated.” See Suskin, “Bet You Didn’t Know… What the Talmud Says about Gender Ambiguity,” Lilith (Spring 2002), accessed June 17, 2019, https://www.lilith.org/articles/bet-you-didnt-know-what-the-talmud-says-about-gender-ambiguity/.

- Dr. Rabinovitz invoked the following medical experts: Eugen Steinach (1861-1944), an Austrian physiologist and pioneer in endocrinology, who helped to identify testosterone through his experiments on guinea pigs; Serge Voronoff (1866-1951), a Russian-French surgeon whose experiments in grafting “monkey glands” (testicle tissue) on the testicles of men have since been largely discredited; and Charles-Édouard Brown-Séguard (1817-1894), a French-American physiologist and neurologist who—according to the Wikipedia article on him—was “a controversial and eccentric figure…known for self-reporting, at age seventy-two, ‘rejuvenated sexual prowess after subcutaneous injection of extracts of monkey testis.’”

- Hoffman, The Passing Game, 132.

- Chauncey, Gay New York, 190. During the 1920s, as Chauncey relates, Greenwich Village—a fifteen-minute walk from Second Avenue—developed as a middle-class mecca of gay-and lesbian-friendly clubs and speakeasies.

- Schwartz’s production of Hinkemann had its Buenos Aires premiere at the Teatro Nuevo on July 6, 1930.

- At the New York premiere, for example, Rosa Goldberg was Beatrice opposite Goldenberg’s Morris.

- N. M. [Nakhmen Mayzil], “Farn nayem teater-sezon: Semuel Goldinburg in Yo a man nisht a man,” Literarishe bleter, August 24, 1934. Mayzil’s disdainful review pairs Yo a man, nit a man with another of Goldenberg’s favorite vehicles, In a Romanian Tavern, which the actor had staged in Warsaw earlier that summer.

- Zolatarefsky’s 1910 potboiler served as the chosen vehicle for Stella Adler’s benefit performance at the Teatro Excelsior, shortly before her departure from Buenos Aires in early September 1930.

- Kesner, “Di mitenvokhige pyesen.”

- Chauncey, Gay New York, 301 & 341.

- Hoffman, The Passing Game, 71.

- Kesner, “Di mitenvokhige pyesen.” A search of the keyword tumtum(טומטום) in the Historical Jewish Press Project (JPress) database yields results in the Yiddish press where this term was used both literally and metaphorically.

- Chauncey, Gay New York, 313.

- See, for example, the following front-page newspaper articles, which appeared the morning after the police raids: “Police Raid Three Shows: Sex, Captive and Virgin Man; Hold Actors and Managers,” The New York Times, February 10, 1927; “Politsey arestirt aktyorn un menedzhers fun dray Brodveyer shous,” Forward, February 10, 1927. These plays and other gay-themed entertainments are discussed by George Chauncey in Chapter 11 (“’Pansies on Parade’: Prohibition and the Spectacle of the Pansy”) of Gay New York. Among the plays that he mentions are The Captive, by Édouard Bourdet (a three-act melodrama dealing with lesbianism, produced in 1926 and suppressed in 1927), and Mae West’s play The Pleasure Man (produced in 1928), which ended with a drag ball.

- Buchwald, “Eyropeyer drame oyf second evenyu.”

- In this connection, the Wikipedia entry on the French surgeon Serge Voronoff notes the following: “’The Adventure of the Creeping Man’ 1923 is one of twelve Sherlock Holmes short stories (fifty-six total) by Arthur Conan Doyle in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes first published in Strand Magazine October 1921 – April 1927. In the story a professor injects himself with an extract of langur, with Jekyll-and-Hyde consequences.The song ‘Monkey-Doodle-Doo,’ written by Irving Berlin and featured in the Marx Brothers film The Coconuts, contains the line: ‘If you’re too old for dancing/Get yourself a monkey gland.’ Strange-looking ashtrays depicting monkeys protecting their private parts, with the phrase (translated from French) ‘No, Voronoff, you won’t get me!’ painted on them began showing up in Parisian homes. At about this same time, a new cocktail containing gin, orange juice, grenadine and absinthe was named The Monkey Gland.” The eight-page Yiddish play script, which was registered for U.S. copyright on October 19, 1925, is by Abraham Blum. It includes the lyrics for four songs; among them are “Monkey Glands” and “Molly Dolly,” a signature number for Molly Picon (the music for “Molly Dolly,” composed by Joseph Rumshinsky, is not included in Blum’s script). See Zachary M. Baker (with assistance by Bonnie Sohn), The Lawrence Marwick Collection of Copyrighted Yiddish Plays at the Library of Congress (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2004) 31, item 96, accessed June 13, 2019, https://www.loc.gov/rr/amed/marwick/marwickbibliography.pdf.

- However, I have not encountered references to Morris as androgunus.

- Indeed, for all we know, the treatment of this character in the French version of the play (if such existed) may actually have been closer to the ways in which novelists like Blair Niles depicted gay male protagonists in their books. (“Society had made him ashamed of what he was,” etc.)

- For lack of concrete evidence, such as access to scripts of both versions of the play, this remains, of course, rank conjecture on my part.

Article Author(s)