The Yiddish Theatre Time Machine

Earlier this year, the DYTP had its biennial workshop at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. To start, as an ice breaker, we went around the table sharing what Yiddish theatrical performance we wished we could have attended. Here is some of what we came up with. Where would you want to go?

The Creepy and the Spooky: Svengali on the Yiddish Stage

Zachary Baker

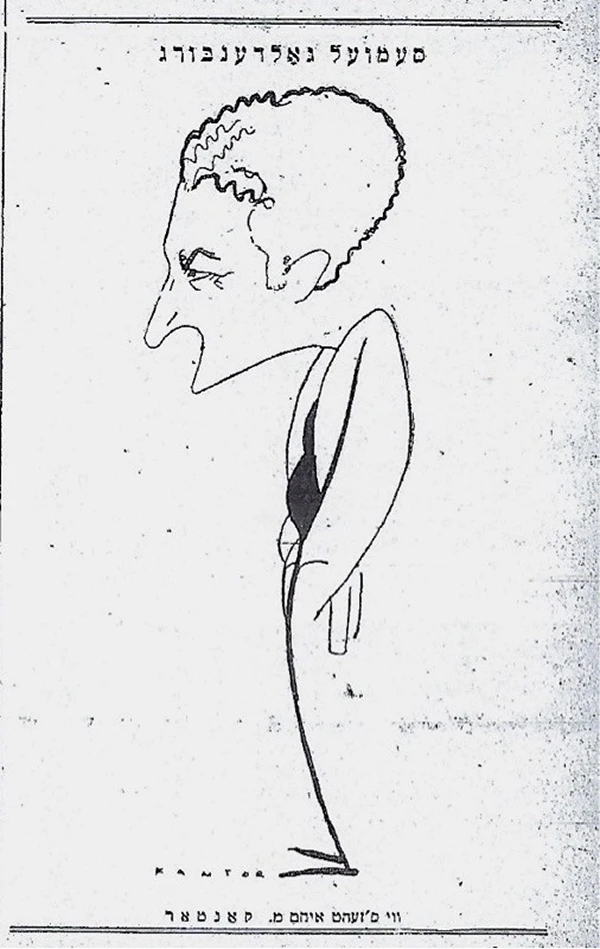

It would have to be a play with Samuel Goldenberg in it, given my current research project. Theatre critics admired Goldenberg’s talents but frequently derided his heavy reliance on the so-called shund repertory. The “serious” dramas that Goldenberg put on were generally translations of works by European literary authors such as Strindberg, Tolstoy, and Artsybashev. However, he also had a soft spot for less conventional plays. Among his signature roles were the androgynous Morris Green in Yo a man, nit a man [Man, Not Man], and Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde.

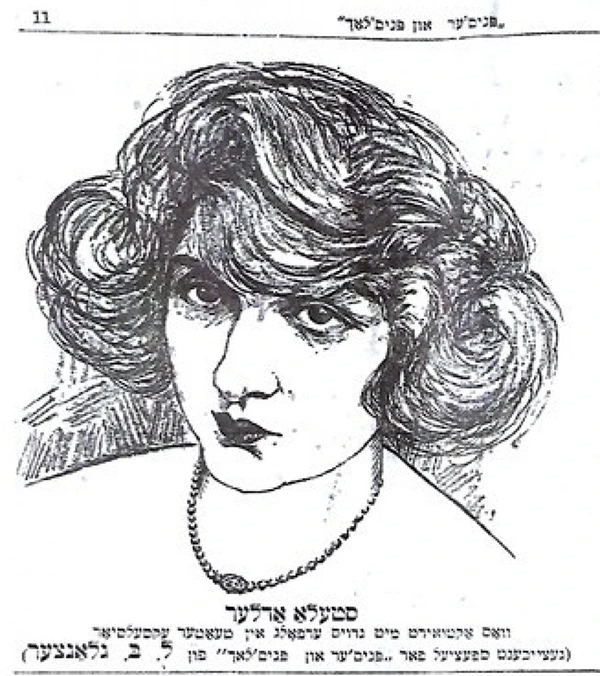

We sometimes overlook the international repertory, in assessing the legacy of the Yiddish theatre. The performance that I would like most to have seen is the Buenos Aires production of the play Trilby (adapted by Mark Schweid from the novel by George DuMaurier), with Samuel Goldenberg in the role of the sinister Svengali, opposite Stella Adler as Svengali’s victim, Trilby. (Musical accompaniment was provided by the Argentine composer Jacobo Ficher.) The local critics considered it to be one of Goldenberg’s most effective productions during his 1930 tour. Like An-sky’s Dybbuk, Trilby was a spooky play that offered Yiddish actors an opportunity to deliver a dramatic punch.

Laying the Foundation for Modern Yiddish Comedy

Joel Berkowitz

Sometimes I get a little greedy, so it’s asking a lot to offer me a time machine and then limit me to visiting just one production from the storied past of the Yiddish stage. What I would really like is a global, multi-century tour, stopping at such times and places as a Purim play in medieval Frankfurt, Avrom Goldfaden’s legendary 1876 appearance on the stage of a Romanian beer garden, the premier of The Dybbuk in Warsaw in 1920, a Soviet Yiddish confection like GOSET’s Constructivist reworking of Goldfaden’s The Sorceress in 1922 … I could go on.

But I’ll venture slightly off the beaten path, to what was likely a reading rather than a full production. The time: the mid-1790s. The place: a well-appointed drawing room (or so I imagine) in Berlin. The occasion: a reading of arguably the first modern Yiddish play—Aaron Halle Wolfssohn’s Laykhtzin un fremelay (Silliness and Sanctimony).1 What draws me to this time and place is the fact that the Wolfssohn and a handful of other maskilim, or proponents of the Jewish Enlightenment (haskalah), laid the foundation of modern Yiddish drama decades before any sustained professional Yiddish theatrical activity existed. So who took part in such a reading? What were their performances like? How did they deal with—and react to—the complex mixture of languages (German/Yiddish/Hebrew-Aramaic) and registers the playwright so carefully wove through the play? Was there an audience beyond the readers? If so, who were they, and what did they think of the play? And did Wolfssohn hand out an early draft that changed considerably in response to audience feedback, or did he wait for his work to be published in 1796 before putting it on its feet—or at least on its seat?

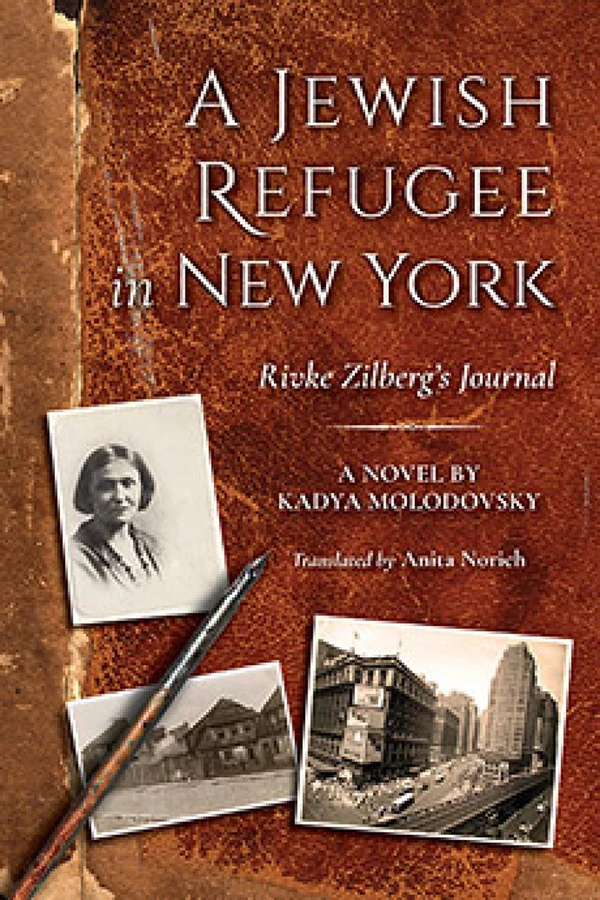

A Jewish Refugee on Broadway

Sonia Gollance

The production I’d like to see was from the 1950s, but first I have a prologue from the 1940s. In May 1941, World War II raged, the Nazi leadership had decided to annihilate European Jewry, and the United States was months away from joining the war. In New York, Yiddish writer Kadia Molodowsky published her first installment of a novel in the Morgn-zhurnal (Morning Journal). This novel, Fun Lublin biz Nyu-york: togbukh fun Rivke Zilberg (From Lublin to New York: Diary of Rivke Zilberg) was published in book form in 1942. Just a few weeks ago, I was delighted to receive my copy of Anita Norich’s new translation of Molodowsky’s novel, A Jewish Refugee in New York: Rivke Zilberg’s Journal, a title which reflects the original title of the serialized version. Written in the form of a journal, the novel engagingly recounts the experience of Rivke Zilberg, a twenty-one-year-old Jewish woman who has fled Nazi-ravaged Lublin to live in New York with her aunt. It covers a ten-month period between 1939 and 1940, during which Rivke anguishes over the fate of her surviving family, tries to make a new life for herself in America, and expresses her dismay over her peers’ blithe disregard for the catastrophic news from Europe. I first read the original several years ago, and it is one of the texts I analyze at length in my book manuscript. I also highly recommend Norich’s translation, which I am assigning to students in one of my classes.

Over a decade after she wrote her novel, Molodowsky returned to Rivke Zilberg’s story with a dramatic adaptation called A hoyz af Grend Strit (A House on Grand Street). Produced by Benjamin Rothman and directed by Yonas Turkow, the three-act play premiered on October 9, 1953–and on Broadway, no less, at the President Theatre on West Forty-Ninth Street. The production was part of an effort to establish a permanent Yiddish acting company on Broadway. The New York Times acknowledged that Molodowsky “has been a leading Yiddish poet for more than thirty years” and added that she “should be encouraged to write more [plays] and with more humorous spots […] She has a natural flair for comedy.”2 Although Variety complimented the acting and cast, it complained that the play was “static and talky” and unlikely to reverse the decline in the popularity of Yiddish theatre productions.3 In stark contrast to contemporary Second Ave. plays, the review continued, Molodowsky used “real, deep Yiddish Yiddish as compared to the popular move toward English Yiddish.” This style “may attract some of the oldsters” but second generation Americans “will find it tough to take.” What was it like to attend a play in Yiddish in the early 1950s that discussed the Holocaust? Who attended it and why? I’d like to imagine that Molodowsky had hordes of giddy fans lining up and clutching well-worn copies of her poetry and prose works, but how much did the audience pay attention to the author and her literary reputation? To her social criticism? I’m confident Norich’s translation will help raise awareness of this fascinating work, even though you need to visit the archives to check out the dramatic version. I, on the other hand, will just set the Time Machine to 1953.

A Forgotten Flop

Barbara Henry

We know so much more about the good Yiddish dramas than we do about the bad ones. Flops disappeared from marquees and memory, leaving behind only savage reviews, if that. Some of that mystery attends the very reduced run of Jacob Gordin’s portentous symbolist drama Oyf di berg (In the Mountains), which opened (and closed) in the spring of 1907. No one remembers exactly when. Oyf di berg is set in the Catskills, where vacationing city Jews are behaving badly and provoking the ire of the “Spirit of the Mountains.” The Catskill Mountains, that is. It is an actual speaking part. As is that of a character named “Feedbag” (Torbe). That’s Meylekh (King) Feedbag to you. What was the audience’s reaction to this leadenly tendentious play? Did the crowd behave like unruly Yiddish theatre audiences of old, hurling rotting produce and insults? Or were they cowed into polite, embarrassed silence, slipping out of the theatre as discretely as possible? We will never know. The play was never performed again, and even though the text has survived, no one has seen fit to stage it since. I would like to have seen Yiddish theatre when a playwright could experiment with difficult new styles; when the fate of the art did not hang on a play’s being a landmark production, a runaway hit, an international phenomenon. When Yiddish plays could just fail, and rise again.

A Real-Life Exorcism

Faith Jones

My great-aunt in New York was once exorcised, probably under the influence of The Dybbuk’s first American run in 1921. She was a young teen and began saying the things you most certainly are not supposed to say: that the family was abusive, that she was in danger. These speech acts led her mother, a Westernized Jew with no prior expression of superstitious beliefs to decide my great-aunt was possessed. They sought out an old rabbi, a recent immigrant who would be willing to perform the unbearably old-fashioned ritual, and she was rid of her demon. This event left her terrified and ashamed, and it performed the desired effect of silencing her. She only told my mother about her exorcism late in life, when everyone else involved was dead. In the intervening years, I do not believe she had been happy even once. She was generally unpleasant, not surprisingly, and I never liked her much, but I have sympathy. I would love to see that first New York Dybbuk. It is all about the deadliness of silencing women: in my great-aunt’s sad case, the play predicts the very thing it gave rise to. And if the message my great-aunt’s mother took from it was all wrong—that it was acceptable to use ritual to deflect women’s legitimate anger—it is still extraordinary that she was willing to take advice from a play in the Yiddish theatre.

So, I would like to see this production, the 1921 American Dybbuk, which had such a profound and tragic effect on my poor, unlikeable great-aunt.

Brothel Drama in Buenos Aires

C. Tova Markenson

I would time travel to an early twentieth-century production of Peretz Hirschbein’s Miriam in Buenos Aires (1908/1909). This production fascinates Yiddish theatre historians for surprising reasons; rather than focusing on the performance’s star actress, stage legend Fanny Wadia-Epstein, historians fixate on the audience’s response. Allegedly, act four (which takes place in a brothel) inspired spectators to cry out in protest against the Argentine Jewish community’s notorious involvement in sex trafficking. According to theatre chroniclers from the era, these words of protest escalated into physical altercations between audience members over the Yiddish theatre’s relationship to the commercial sex trade. I would be eager to gather additional perspectives on this history through schmoozing with fellow theatregoers, comparing my own observations about the audience’s response against the historical record, and interviewing Fanny Wadia-Epstein.

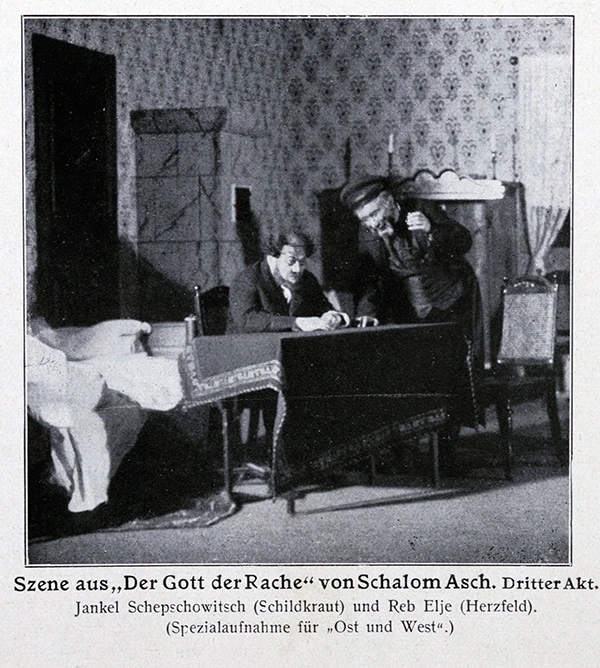

Meine Damen und Herren – Sholem Asch!

David Mazower

I would set my time machine to Tuesday, March 19, 1907. Finland has just become the first country to elect women to parliament, the electric washing machine is about to be unveiled, and Florenz Ziegfeld is assembling his first Broadway Follies show. Meanwhile, in a sensational breakthrough for Yiddish drama, it’s showtime at the über-prestigious Deutsches Theater in Berlin. The house lights are about to dim—it’s the opening night of Der Gott der Rache, the world premiere (in German translation) of Der got fun nekome (The God of Vengeance) by my great-grandfather, Sholem Asch. (If you don’t know the play, here are some keywords: brothel, prostitutes, pimp, Poland, Jews, virgin daughter, lesbian kiss, God, Torah, scribe).

Asch had suffered two crushing setbacks in his efforts to get the play staged: his mentor Peretz had advised him to destroy it, and the star actor-manager Jacob Adler had rejected it to his face (“You want me to perform this play in front of Jewish women? Never!”)

Undaunted, the twenty-six year old Asch had found an introduction to director Max Reinhardt, travelled to Berlin, and read his play in Yiddish to Reinhardt and some close associates. The renowned German director championed the play at once, as did his dramaturg, Efraim Frisch, a former rabbinical student.

The buzz on opening night must have been incredible. I imagine Asch pacing nervously on the biggest night of his career. I’d love to ask Reinhardt what convinced him to take a punt on a little-known Polish-Yiddish dramatist. And more than anything, I’d love to eavesdrop on the audience as they see Rudolf Schildkraut (famous for his Shylock, King Lear, etc.) create the role of the Jewish brothel-owner whose dream of a fresh start for his daughter comes crashing down around him.

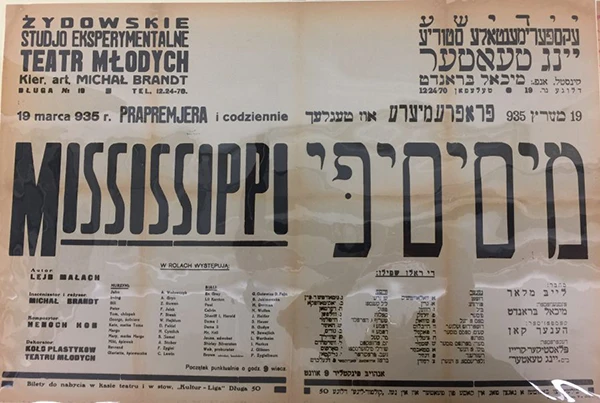

Mississippi in Warsaw

Alyssa Quint

I would want to go back and see the 1935 production of Leyb Malakh’s Mississippi, which was commissioned and staged by Michał Weichert in Warsaw. It went on to play different venues throughout Poland and was staged over 100 times.

Mississippi was a play based on the Scottsboro Boys. The Scottsboro Boys were nine African American teenagers, ages thirteen to twenty, falsely accused of raping two white women on a train in Scottsboro, Alabama in 1931. Mississippi was written in 1933.

The play begins, for instance, in a moving freight car where the seven African American young men and boys (Malakh reduced the number of boys from nine to seven) get to know each other as they traveled between Chatanooga and Memphis, revealing their backstories to the audience: it is 1931, and they jump on and off the train looking for work. Tensions rise as two white women are snuck into the same boxcar by the train’s conductor, and, a few stops later, two white men enter who get into a fist fight with one of the African American boys who throws them off the slow-moving train. When the train reaches its final stop, an angry lynch-mob is surrounding the box-car and the sheriff reveals that the white men had called the station accusing the boys inside of raping the women. The sheriff can only barely restrain the mob as it cries: “Pull them out! Lynch the devils!”

The play features brief vignettes that were performed almost simultaneously on multiple stages among audience members. In one scene, for instance, members of the racist Lily White Movement lavish gifts and sympathy on the female accusers; one of the boys in prison recalls the ugly racist chant of the Klu-Klux Klan as he was forced to watch as they set a man on fire; a priest visiting the boys in prison presides over mass, all in Yiddish. Malakh’s script is also embedded with original songs by the composer Henekh Kon, perhaps the most important and prolific musical talent of the interwar Yiddish stage. Kon composed songs in the style of the African American musical tradition including a gospel song and African American spirituals that reference the enslavement of African people. A cabaret singer in a Harlem night club sings a Yiddish-language jazz song.

Malakh did not turn the Scottsboro trials into a courtroom drama; in bits of dialogue, the play clarifies the irreversible nature of the boys’ tragic situation. If we are free, one of them says to the others, for instance, we will be lynched or we will always fear being lynched. Now that they have been accused, they (alongside the audience) come to the realization that they are safer in jail. Another scene sheds light on the social reverberations of this tragedy: a woman calls over an African American boy to shine her shoes on the streets of New York. He can’t, he replies, as he doesn’t want to be accused of rape. Yet another illuminates the cruelty of the accusers. Mississippi is an unflinching look at racism of the Jim Crow Era.

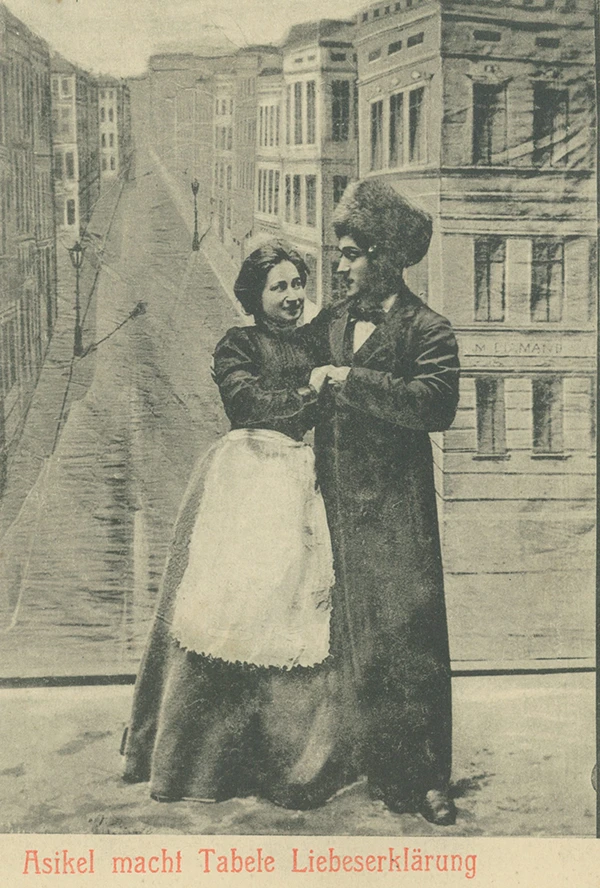

Broder Singers Live!

Amanda (Miriam-Khaye) Seigel

I would love to see a performance of the Broder Singers, the first secular Yiddish performers. Jacob Mestel (1884-1958) recalled seeing them in Zloczew as a child, around 1893. Two women and three clean-shaven men (“like priests”) opened with an a capella song. Khone Shtrudler sang a humorous piece—perhaps with some of his famously improvised, sometimes risqué rhymes. Fayvl and Saltshe Vayzenfraynd (parents of Paul Muni), sang Berl Broder’s comic duet, Der shuster mitn shnayder with Saltshe in male drag as the tailor. Then, two “Hasidim,” “Shmerke un Berke,” emerged: “one sat on the other’s lap and while the one in front was telling of miracles performed by his rebbe, the one behind was gesticulating (blowing the nose of the one in front, caressing his beard, and scratching his throat)… so that it seemed like they were one person.” A few years later, as recalled by M. Myodavnik, a different Broder Singers performance of King Ahasuerus in Bendin was marred by unintentional slapstick: the horse carrying Mordecai repeatedly threw him off, and thrifty theater-goers who were watching the play through a hole in the roof (to avoid buying tickets) fell down onto the stage during the performance.

Paris, 1945

Nick Underwood

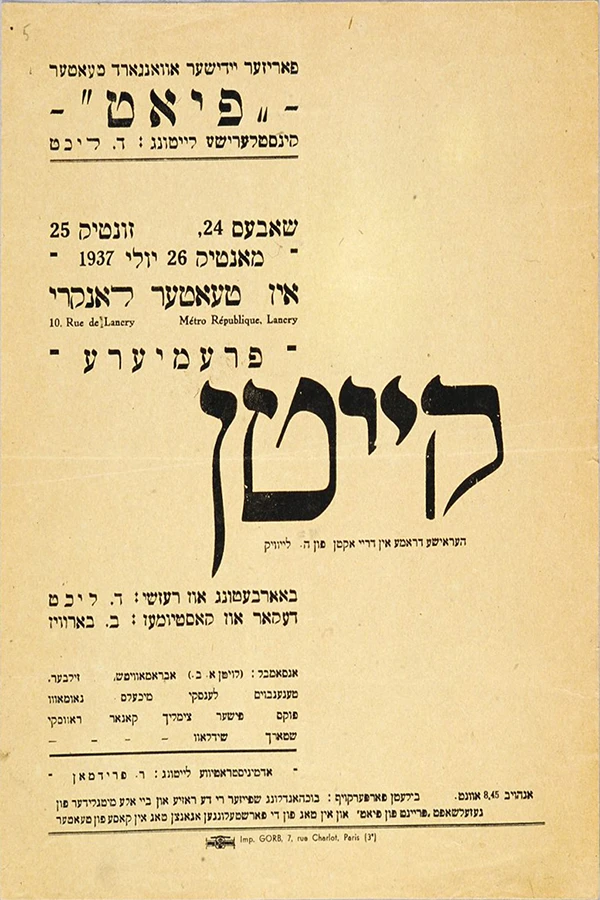

If I could hop into the phone booth, I would set the date and time for 8pm on July 11, 1945 so that I could try to get a seat at Salle Pleyel to see the Parizer yidisher avangard teater (PYAT) make their postwar comeback appearance in Paris. PYAT, as they were known, was 1930s Paris’s primary contribution to Yiddish theatre, and, as soon as they could amass a troupe, they staged their triumphant and defiant return to the Parisian stage to celebrate their tenth anniversary.

That evening, the PYAT members who were in Paris staged three short pieces: a “montage” of H. Leivick’s Di oreme melukhe (The Impoverished State), which Jacob Rotboym of Vilna Troupe fame directed and which PYAT premiered before the war in January 1939; Der sod (The Orchard) by R. Sander, which is described as “a one act drama from the time of the occupation adapted for the stage by A. Fesler [most likely Oscar Fessler]”; and Mazel Tov, described as “a people’s play [folks-shpil] by Sholem Aleichem, adapted for the stage by M[oishe] Kinsman,” who was an actor director with the troupe in the 1930s and survived the war in hiding in France.4

According to the playbill:

PYAT’s ten-year anniversary is a holy day for Yiddish art theatre. For ten consecutive years there was a group of Jewish workers and intellectuals in France that, through strong and talented actors, transmitted important stories; without money, without funding, they produced lovely plays and created a good Jewish theatregoing public.

With this ten-year anniversary program, PYAT has produced an impressive program. They will spiritually encourage and lift our brothers and sisters and glorify the bright memory of our murdered and fallen fighters.

Ten years of PYAT – Today a modest amount of extremely great works of wonderful material, inspired by the noble ideals of a great revolutionary movement.

I would have loved to have been there.

Article Author(s)

Zachary Baker

Zachary Baker was the Reinhard Family Curator Emeritus of Judaica and Hebraica Collections in the Stanford University Libraries.

Joel Berkowitz

Joel is professor of English and director of the Sam and Helen Stahl Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Sonia Gollance

Sonia Gollance is an associate professor in Yiddish at University College London.

Barbara Henry

Barbara Henry is associate professor of Slavic Languages & Literatures at University of Washington.

Faith Jones

Faith Jones is a librarian, translator, and researcher in Vancouver, Canada. Her work focuses on gender in Yiddish culture. She is currently working on a book-length translation of stories by Soviet author Shira Gorshman.

C. Tova Markenson

Dr. C. Tova Markenson is a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Research on Antisemitism at Technische Universität Berlin.

David Mazower

David Mazower is the Bibliographer and Editorial Director at the Yiddish Book Center and the co-editor with Aaron Lansky of the Center's English-language magazine Pakn Treger.

Alyssa Quint

Alyssa Quint is Leo Charney Visiting Fellow at the Center for Israel Studies at Yeshiva University.

Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel

Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel, is a Yiddish singer, songwriter, actor and researcher in Yiddish culture.