The World of Sara Levy

IN SEPTEMBER 2014, I co-organized, with Dr. Rebecca Cypess, a musicologist and musician, a multi-disciplinary symposium at Rutgers University, “Sara Levy’s World: Music, Gender, and Judaism in Enlightenment Berlin,” which focused on the role of aesthetics—particularly music—in the lives of late eighteenth-century Prussian Jews. Staging two readings (in both Hebrew and Yiddish) of a scene from Aaron Halle Wolffsohn’s hilarious and biting satirical play Laykhtzin und fremelay (Silliness and Sanctimony, 1790). The play pits aesthetics and Jewish tradition squarely against one another, with Jewish women the leading culprits in a headlong rush into excessive and ruinous modernization through music. With it, we invited our audiences directly into the salon culture that the symposium explored.1

Wolffsohn (1756-1835), a maskil, was a member of the first generation of Prussian Jews to attempt to live as modern Europeans. He arrived in Berlin, the capital of both the Prussian Aufklärung and the Haskalah, in 1785. A gifted author in three languages, Wolffsohn soon became part of the circle around the renowned philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, and began to write for the Hebrew Haskalah journal, Ha-me’asef (The Gatherer), becoming its sole editor in 1794-1797. Dedicated to the early Haskalah’s moderate pathway of modernization, the journal encouraged Ashkenazic Jewry to shed their “obscurantist” piety and to pursue reform in the spirit of “reasonable” religion, without succumbing to the blandishments of the pseudo-Enlightenment. Yet Wolfssohn found himself in a state of despair toward the century’s end. The Jewish bourgeoisie appeared to be abandoning the world of their ancestors in their efforts to become modern Germans — almost as quickly as they discarded the Yiddish vernacular for High German. He pointed his satire directly at them.

The play, inspired by Molière’s Tartuffe, unfolds in the home of Reb Henokh, a Court Jew and recent returnee to devout religious practice, who has hired a certain Reb Yoysefkhe from Poland to tutor his son, Shmuel, in traditional Jewish subjects. The Polish-Jewish tutor, however, is not what he appears to be. With designs on Reb Henokh’s spoiled daughter, Yetkhen, whom he tries to woo—all the while chasing the household maid and being a regular client at a working-class brothel—Reb Yoysefkhe is a hypocritical charlatan. Yetkhen herself is likewise flawed. She is beautiful, intellectually and musically gifted, yet superficial. The rest of the cast of characters do not fare much better from Wolfssohn’s pen: only uncle Markus, the prototypical maskil, sage, calm, and reasonable, is exemplary.

In Act 2, scene 4, Reb Yoysefkhe interrupts Yetkhen when she is playing a keyboard instrument, likely a fortepiano, to declare his marital intentions — which her father has previously approved. The scene underscores Reb Yoysefkhe’s hypocrisy as he attempts to sit as closely as he can to Yetkhen while she is playing, and he asks her to sing, clearly contravening the halakhic demands of modest behavior between unmarried men and women. Wolffsohn does not hesitate to eroticize the scene when in response to the tutor’s moves, Yetkhen warns him to back off, lest her powder soil his clothes. He cheerily responds, “Don’t worry, you can get me all powdery if you like,” and later boasts that he knows “what to do with a woman.” When Yetkhen understands that Reb Yoysefkhe is her intended, she rebuffs him soundly, calling him “a drunken Polish swine.” Enraged, he strikes her instrument, and Yetkhen cries out, in a Judeo-German that illustrates her acculturation, “mein schönes Klavier ist ganz kaput” (“My beautiful piano is completely destroyed”), closing the scene.2

Wolffsohn focused on Yetkhen’s engagement with music because its individual study and performance, its patronage through financial support of composers, as well as the commissioning of pieces, their singing, and the hosting of private and semi-public salons formed an indispensable part of the lives of the Berlin Court Jews in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Music was an essential component of Bildung, the broad ideal of individual moral improvement and humanistic cultivation, which would foster a more capacious civic sphere that was a hallmark of late eighteenth-century enlightened Europeans. Both ideologically motivated maskilim and the acculturating members of the social elite considered aesthetics crucial to their negotiations with European culture.

As Wolfssohn’s play shows, their negotiations were gendered, both in the different ways in which Jewish men and women could—and did—partake in European culture, and in the symbolic value attached to their participation, and how it was interpreted. In the eyes of the maskilim, traditional Jewish education was an obstacle to Bildung. Its curriculum focused too heavily on the Talmud, and it depended upon Yiddish, which they considered a shameful zhargon or bastardized dialect of German, as the oral conduit for sacred Hebrew scripture. Its goals were to form talmidei hakhamim (male Torah scholars), not members of the Gebildetebürgertum. Daughters posed a different set of problems. In traditional homes, girls in Ashkenazic Jewish society learned religious essentials mimetically through their domestic relationships with their mothers, aunts, cousins, and sisters. When maskilim waged a full-throated attack on the limits of a talmudic-centered education for boys, they also sought to include Jewish daughters in their modern pedagogical efforts. Yet when the elite Court Jewish families supplemented their daughters’ education, they generally did so in order to rear them to be cultivated bourgeois housewives. Jewish daughters were schooled not only in the “gentile” arts of writing, speaking, and reading in German and French, but in dancing and singing; in studying and commissioning musical work; and in enjoying and performing music. Keyboard lessons were a required part of their education.

Our book focused on the world of Sara Levy (1761-1854), the fifth daughter of the prominent Court Jewish family, the Itzigs, who made their home in Berlin in the second half of the eighteenth century. Daniel Itzig, Sara’s father and the principal supplier of the Prussian mint, was able to create a lifestyle commensurate with elite gentiles of his period. The Itzigs adopted the mores, values, and social practices of the surrounding culture. They built an extraordinary home, collected art, became patrons of music, and insisted that their children become proficient at the keyboard. Daniel Itzig hired Johann Philipp Kirnberger, a student of and advocate for the famed Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach, for Hanna and Bella, his two eldest daughters. Sara’s younger sister Fanny, later a famous Viennese salonnière in her own right, was an instrumentalist who helped establish the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, and later created the music hall that became home to the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. She and her husband Nathan Arnstein gave Mozart domicile in their home in 1781. Sara Levy studied with Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, son of J. S. Bach, and became an accomplished keyboardist. She commissioned progressive and noteworthy compositions from both Friedemann and his brother Carl Philipp Emanuel, and she owned a massive collection of music manuscripts and printed editions of music from her own day and from the previous generation. She became a patron of both the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin, a bourgeois choral society to which she donated music, including instrumental pieces, solo works, chamber music, symphonies, and keyboard concertos, many by the Bach family. The collection is today one of the most important archival repositories of the Bach tradition. She also supported a Jewish orphanage in Berlin, and was a well-known salon hostess.3

While other members of her family became Protestant Christians, Sara Levy remained faithful to her origins. Unusually, for her circle, Sara Levy was able to combine her participation in and dedication to German and European culture with an uninterrupted commitment to Jewish affairs in a way so many of her contemporaries, including many of her friends, were unable to achieve. For Levy, deep engagement with music—even with a tradition dominated by Christian motifs—did not threaten her Jewishness.

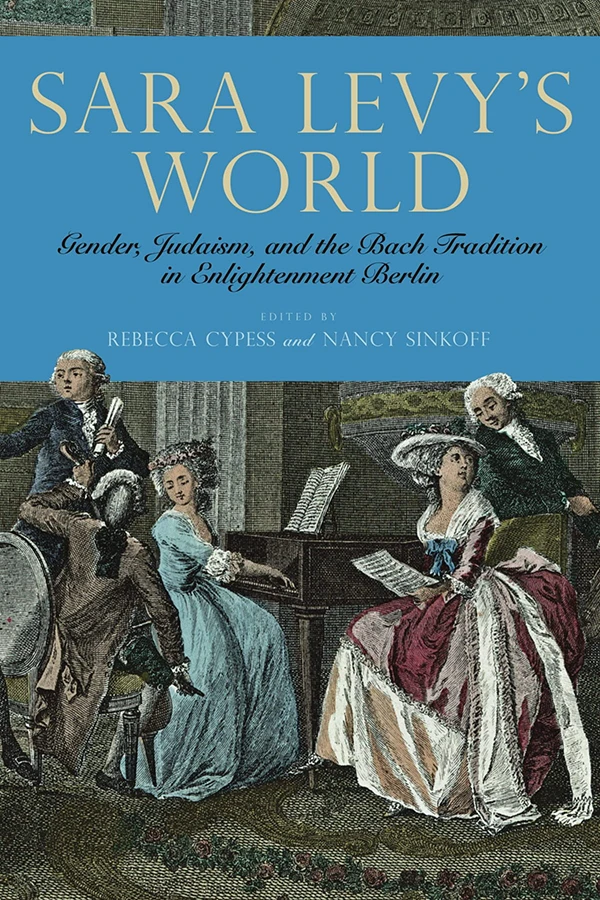

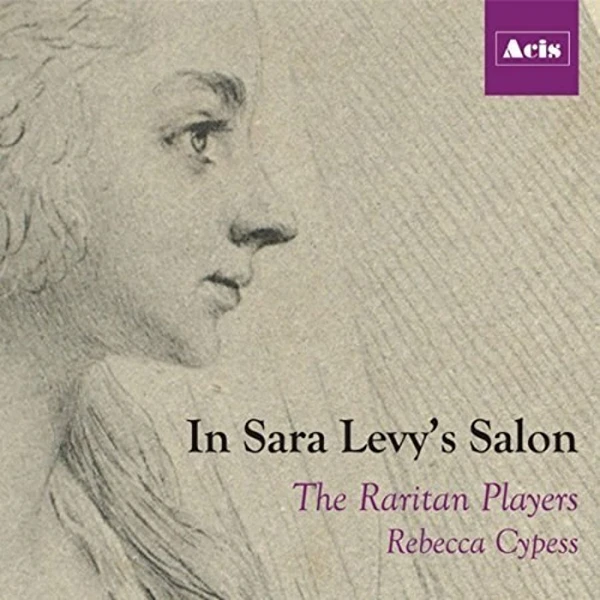

Our symposium engaged the philosophical, theological, aesthetic, theatrical, political, social, and sonic influences on Levy’s life. It generated several recital-lectures, a CD produced by Rebecca Cypess of music from the Sing-Akademie’s archive, and a book, Sara Levy’s World: Gender, Judaism, and the Bach Tradition in Enlightenment Berlin. Both the symposium and the book examined Levy’s life through their own subjectivity and not through the lens of a maskilic parody. Although Wolffsohn’s stunning play invited his contemporaries and later generations to understand the anxieties of maskilim living in late eighteenth-century Prussia, it did not give women like Sara Levy their due. Preoccupied as he was with the radical pace of modernization among many of Levy’s contemporaries, Wolffsohn could not appreciate the singular role Levy and her family played in German musical history. Nor could he fully understand that she shared, with him, a worldview that was both Jewish and European. Superficial she was not.

Notes

- On the play, see Joel Berkowitz and Jeremy Dauber, eds. and trans., Landmark Yiddish Plays: A Critical Anthology (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006), 10–18 and Shmuel Feiner, The Origins of Jewish Secularization in Eighteenth-Century Europe, trans. Chaya Naor (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 219–220. On Halle Wolffsohn, see Jutta Strauss, “Aaron Halle-Wolfson: ein Leben in drei Sprachen, Musik und Ästhetik im Berlin Moses Mendelssohns,” in Musik und Ästhetik in Berlin Moses Mendelssohns, Anselm Gerhard, ed. (Tübingen: Max Neimeyer Verlag, 1999), 57–76.

- Aaron Halle-Wolfssohn, “Leichtsinn und Frömmelei: Ein Familien Gemälde in Drei Aufzügen,” in Lustpiele Zur Unterhaltung Beim Purim-Feste (Breslau, 1796), 33–111; Berkowitz and Dauber, Landmark Yiddish Plays, 97.

- On Jewish women in late eighteenth-century Berlin, see Deborah Hertz, Jewish High Society in Old Regime Berlin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988); Deborah Hertz, How Jews Became Germans: The History of Converstion and Assimilation in Berlin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007); Natalie Naimark-Goldberg, Jewish Women in Enlightenment Berlin (London: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2012); Steven M. Lowenstein, The Berlin Jewish Community. On Sara Levy, see Peter Wollny, “Sara Levy and the Making of Musical Taste in Berlin,” Musical Quarterly 77, no. 4 (1993): 651–688 and Christophe Wolff, “A Bach Cult in Late-Eighteenth Century Berlin: Sara Levy’s Musical Salon,” Bulletin of the American Academy 58, no. 3 (2005): 26–39.

Article Author(s)