Matchmaker, Matchmaker, Act on the Stage

Aa far as matchmakers are concerned, love is like poison. Or so claims Khaykelson, a character in a one act play by Avrom Reisen. And Khaykelson might know. Not simply because he is a poet––he is also courting a matchmaker’s daughter. And so, in Dem shadkhns tokhter (The Matchmaker’s Daughter), Reisen poses a question that appears throughout Yiddish drama: What do matchmakers want and how much trouble does it cause young lovers?

Matchmakers played an important role in Yiddish culture. Just ask Molly Picon, the renowned actress who is probably most famous for one of the last roles she performed: Yente the Matchmaker in the musical Fiddler on the Roof, which was based on Sholem Aleichem’s short stories. Matchmakers appear in Yiddish literature, folksongs, and film. In fact, Edgar G. Ulmer’s 1940 film Amerikaner Shadkhn (American Matchmaker) even includes a scene where matchmakers go on strike to protest a wealthy bachelor who decides to arrange matches pro bono. Not surprisingly, matchmakers were a popular character type in the Yiddish theatre. While Naomi Seidman has recently traced the shifting literary portrayal of marriage brokers from nineteenth century memoirs to the twentieth century fiction of Bernard Malamud, there hasn’t been a comparable study of matchmakers in the Yiddish dramatic repertoire. Fortunately, Plotting Yiddish Drama is bringing you the tools to help make that happen.

In a social milieu where arranged marriages were expected and parents sought out connections for their children with similarly-minded families living both close by and far away, someone needed to oversee introductions and negotiations over dowries and provisions for the young couple. While families sometimes proposed matches, such as in Jacob Gordin’s Di shkhite (The Slaughter), these sort of plans could have terrible unforeseen consequences, as can be seen in S. An-sky’s Der dibuk (The Dybbuk). It could be helpful for someone like Mrs. Grossberg, in Sholem Asch’s Um winter (In Winter), to remind people how to behave so that they would be able to get a new couple to the khupe (marriage canopy) successfully. Matchmakers thus performed a crucial job in traditional Jewish communities. Not that this position got them much respect, at least not in popular culture. As one Yiddish folksong says: “You can laugh at the matchmaker / who brings together a wall with a wall.” Matchmakers are frequently represented as buffoonish, comic characters who stutter, mislead, and suffer all kinds of indignities in order to get their shadkhones gelt (payment for making a match). The protagonist of Dovid Pinski’s Yankl der shmid (Yankl the Blacksmith) thinks nothing of physically shoving around Khaye Peshe, the matchmaker he commissioned to broker his engagement. At best, fictional matchmakers are often comic relief. At worst, they remind audiences of the most degenerate “values” parents prioritize over their children’s happiness, since many Yiddish plays show the triumph of love matches over arranged marriages.

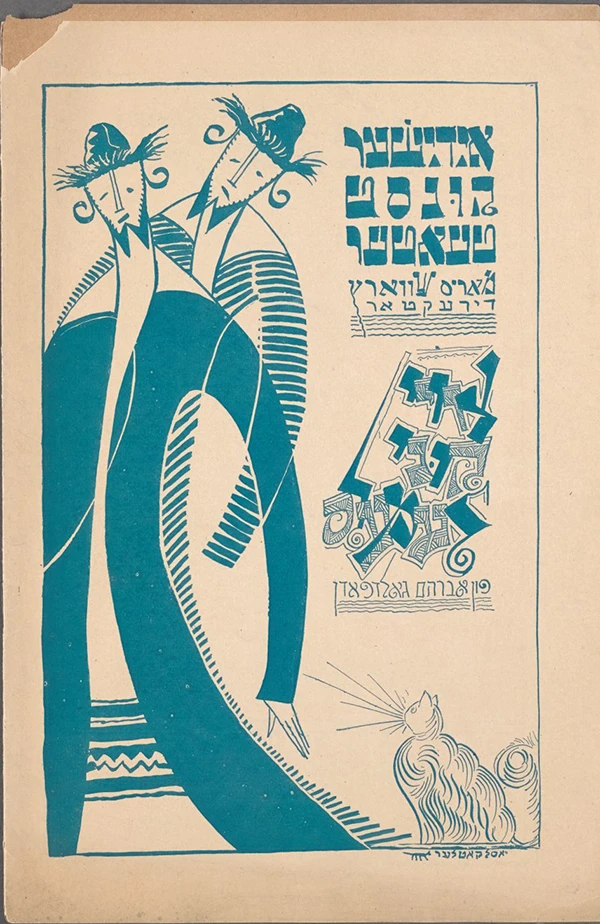

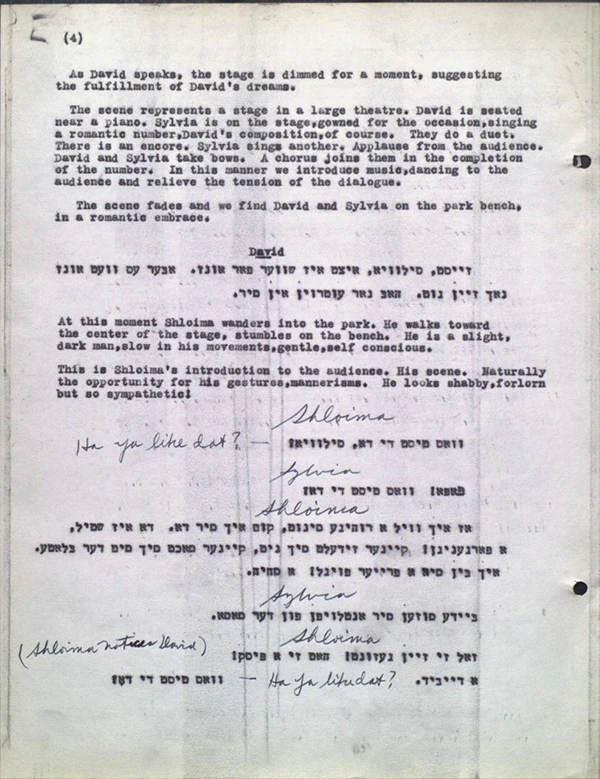

It is telling that even though matchmakers feature in so many Yiddish dramas, they are rarely the protagonists. When I searched through the Lawrence Marwick Collection of Copyrighted Yiddish Plays at the Library of Congress, there were only a few scattered examples of dramas with shadkhn (matchmaker) in the title, such as Belle Markowitz’s 1936 musical comedy Shloima der shadkhn (Shloima the Matchmaker). Markowitz’s play is an entertaining period piece set against the backdrop of the Great Depression. While young people dream of love and careers in show business, Shloima and his wife Rifka go into matchmaking to try to earn a living. Yet instead of banding together, the two frequently work at cross purposes: Shloima considers his profession to be an art and tries to understand the needs of his clients, while Rifka doggedly tries to make as many matches as possible, even if it means proposing candidates for marriage without properly vetting them. Shloima der shadkhn stands out as a play about matchmakers that was set in New York, rather than Eastern Europe. It is also one of the relatively few plays in the Marwick Collection that was written by a woman. Nonetheless, Markowitz does not challenge the negative yidene stereotype of the nagging Jewish matron. Markowitz’s portrayals of both Shloima and Rifka underscore the cultural resonance of male and female matchmaker types. Shloima der shadkhen is also representative insofar as we know very little about the playwright’s life, her play’s development, or any performance history, which is fairly typical for plays that did not have high literary ambitions.

While Markovitz’s life remains (at least for now) a mystery, our current group of plays about matchmakers includes works by some of the best-known Yiddish dramatists. Predictably, this batch includes a selection of Avrom Goldfaden plays. From Kalmen Matchmaker in Di tsvey Kuni-Leml (The Two Kuni-Lemls) to Yudke Fayfer in Di mume Sosye (Aunt Sosye) to Shakhne in Shmendrik, Goldfaden’s matchmakers exemplify the character type that Yiddish playwrights pushed back against as they dramatized the trials and successes of romantic love. And—thinking back to Yente—it would be almost unthinkable to talk about Yiddish matchmakers without including a work by Sholem Aleichem. He is, of course, the writer who dreamed up the matchmaker Menachem Mendl, a man whose head is stuck so far up in the clouds that he accidentally arranges a match for two brides. Sholem Aleichem’s play Der get (The Divorce) is a one act comedy, where Sholem Matchmaker shows up to suggest new matches before the divorce has even been arranged. Matchmakers were comic gold, as far as Sholem Aleichem was concerned.

Yet even a traditionally-minded matchmaker who was dependent on shadkhones gelt for survival might not always be portrayed as bumbling, comical, or mercenary (and not always all of these qualities at the same time). Matchmakers could be convinced of the value of romantic love, especially if a daughter’s happiness was at stake. Note the Matchmaker in Dem shadkhens tokhter learns to appreciate his daughter’s love match. And in an ironic twist, he convinces Khaykelson the poet to consider an arranged marriage. We hope you’ll also come to appreciate the importance of matchmakers––at least as they appear on the Yiddish stage!

Article Author(s)