Sholem Asch: God of Vengeance is Not an Immoral Play

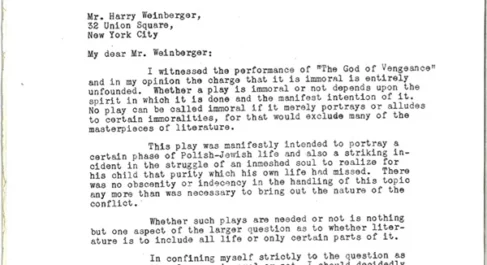

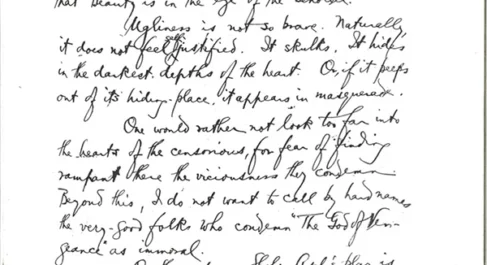

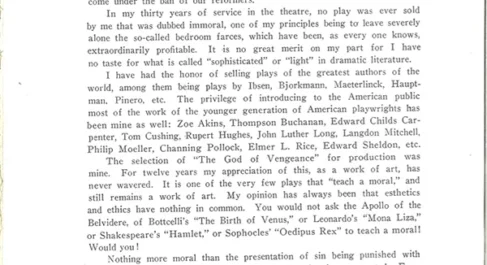

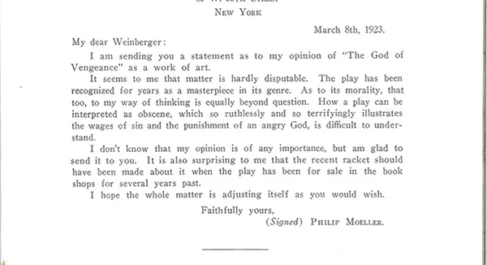

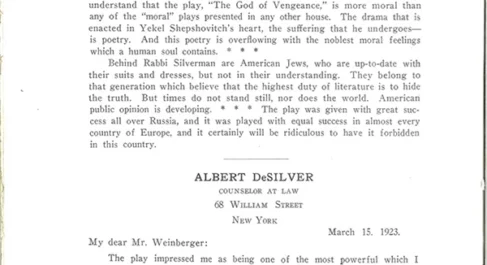

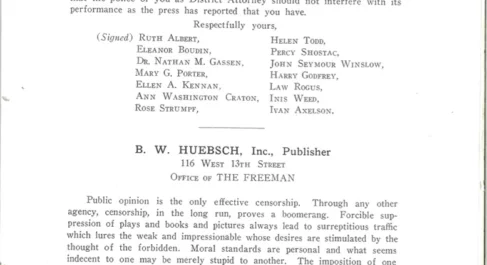

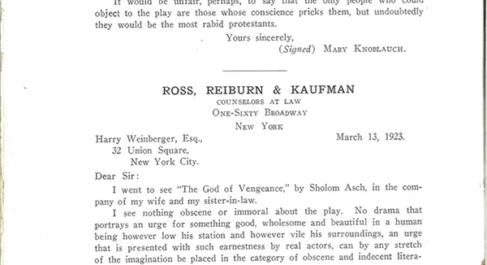

In February 1923, Sholem Asch’s classic Yiddish drama Got fun nekome (God of Vengeance) made its first appearance on Broadway. The English-language production starred the famous German-Jewish actor Rudolf Schildkraut as the brothel owner with a troubled conscience. Within days, a moral crusade against the play began to gather pace. In March 1923, the entire cast and producer Harry Weinberger were indicted and appeared in court, pleading not guilty to the charge of staging an “obscene and impure drama.” As the case continued, Weinberger published a 20-page pamphlet in defense of the play. It contained messages of support from a host of prominent figures as well as members of the public. Constantin Stanislavsky wrote that “God of Vengeance was presented throughout Russia during the days of the Czar and there was no protest against it.” Eugene O’Neill branded censorship “the last cowardly resort of the boob and the bigot.” The final statement was by Sholem Asch himself — an open letter defending his play. The Digital Yiddish Theatre Project is pleased to make this pamphlet available digitally for the first time and to reproduce Asch’s own statement in full.

Open Letter by Sholom Asch

Because of the wrong interpretation of my play, The God of Vengeance, now running at the Apollo Theatre, I wish to make the following statement:

I wrote this play when I was twenty-one years of age. I was not concerned whether I wrote a moral or immoral play. What I wanted to write was an artistic play and a true one. In the seventeen years it has been before the public, this is the first time I have had to defend it.

When the play was first produced, the critics in Germany, Russia, and other countries, said that it was too artistically moral. They said that for a man like “Yekel Shepshovitch,” keeper of a brothel, to idealize his daughter, to accept no compromise with her respectability, and for girls like Basha and Raizel, filles de joie, to dream about their dead mother, their home, and to revel in the spring rain, was unnatural. About two years ago I was approached by New York producers for permission to present the play in English. I refused, since I did not believe the American public was either sufficiently interested or adequately instructed to accept The God of Vengeance.

I don’t know whether I can explain the real feeling I wanted to put into this play. It is difficult for an author to comment on his own work. As to the scenes between Manka and Rifkele, on every European stage, especially the Russian, they were the most poetic of all, and the critics of those countries appreciated this poetic view. This love between the two girls is not only an erotic one. It is the unconscious mother love of which they are deprived. The action portrays the love of the woman-mother, who is Manka, for the woman-child, who is Rifkele, rather than the sensuous, inverted love of one woman for another. In this particular scene, I also wanted to bring out the innocent, longing for sin, and the sinful, dreaming of purity. Manka, overweighed with sin, loves the clean soul of Rifkele, and Rifkele, the innocent young girl, longs to stay near the door of such a woman as Manka, and listen within.

As to the comment that the play is a reflection on the Jewish race, I want to say that I resent the statement that The God of Vengeance is a play against the Jews. No Jew until now has considered it harmful to the Jew. It is included in the repertoire of every Jewish stage in the world and has been presented more frequently than any other play. The God of Vengeance is not a typical “Jewish play.” A “Jewish play” is a play where Jews are specially characterized for the benefit of the Gentiles. I am not such a “Jewish” writer. I write, and incidentally my types are Jewish for of all peoples they are the ones I know best. The God of Vengeance is not a milieu play – it is a play with an idea. Call “Yekel” John, and instead of the Holy Scroll place in his hand the crucifix, and the play will be then as much Christian, as it is now Jewish. The fact that it has been played in countries where there are few Jews, Italy for instance, and that there the Gentiles understood it for what it is, proves that it is not local in character, but universal. The most marked Jewish reaction in the play is the longing of “Yekel Shepshovitch” for a cleaner and purer life. This is characteristically Jewish. I don’t believe a man of any other race placed in “Yekel’s” position would have acted as he did in the tragedy that has befallen his daughter.

Jews do not need to clear themselves before any one. They are as good and as bad as any race. I see no reason why a Jewish writer should not bring out the bad or good traits. I think that the apologetic writer, who tries to place Jews in a false, even though white light, does them more harm than good in the eyes of the Gentiles. I have written so many Jewish characters who are good and noble, that I can not now, when writing of a “bad” one, make an exception and say that he is a Gentile.

Sholom Asch.

Read more about Sholem Asch and Got fun nekome here, here, and here.

Note: The portion of this post that reproduces the text of the original pamphlet follows that text in all respects, including spellings and transliterations that may depart from accepted practice elsewhere.

Article Author(s)