Interview: Sabina Brukner on the Folksbiene’s Yiddish Women Playwrights Festival

In April 2021, the National Yiddish Theater Folksbiene launched its groundbreaking Yiddish Women Playwrights Festival with an online reading of Chava Rosenfarb’s drama of the Vilna Ghetto, Der foygl fun geto (Bird of the Ghetto, one of the very first plays included in the Digital Yiddish Theatre Project’s Plotting Yiddish Drama database). Although the Folksbiene performed shows by Eleanor Reissa, Miriam Hoffman, and Sylvia Regan in the 1990s, those were the only productions of Yiddish-language plays by women in its 106-year history. This reading was the first Yiddish-language performance of Der foygl fun geto, and this festival is almost certainly the first festival of Yiddish women playwrights by a major Yiddish theatre company, thus representing a major step in raising awareness of dramatic works by women who wrote in Yiddish.

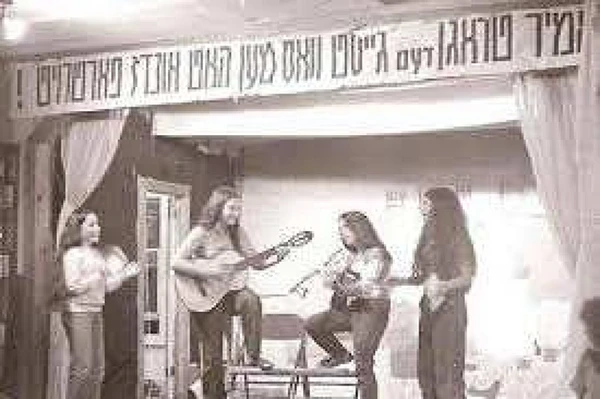

The festival is the brainchild of Sabina Brukner, the Folksbiene’s literary manager. Born to Holocaust survivor parents from Poland (her mother was best friends with Rosenfarb’s younger sister Henya growing up, and attended the same school as Rosenfarb, the Vladimir Medem Shule in Łódź), Brukner came to the United States when she was two, spoke Yiddish at home, and attended the Bundist Yiddishist Camp Hemshekh for eleven summers––Folksbiene Artistic Director Zalmen Mlotek was the camp’s Musical Director. Brukner has continued to be involved in Yiddish cultural activities throughout her life, such as Yugntruf and attending Yidish-Vokh, and was behind the effort to bring Rosenfarb to KlezKamp as an honored guest in 2004. She joined the Folksbiene in December 2017, shortly before their acclaimed production of Fidler afn dakh.

In this interview, Plotting Yiddish Drama Managing Editor Sonia Gollance speaks with Brukner about the festival and raising awareness of Yiddish women playwrights.

Sonia Gollance: How did you get started with the Folksbiene? What is it that you do as literary manager for a theatre company?

Sabina Brukner: I was originally hired mostly to read scripts. They had a backlog of submissions to the theatre. Very few in Yiddish, but a lot on Yiddish, immigrant, and Holocaust themes in English. Very soon after I got there we began preparations for Fiddler on the Roof in Yiddish, and that became the main thing I worked on for the first year and a half I was there: transliterating the script from Yiddish and back translating it so the actors knew what their lines actually meant, working as script supervisor and as a Yiddish coach. But in between, I was still reading scripts and thinking ahead, and one of the jobs I was given was to develop a good history of the Folksbiene. We had had our hundredth anniversary, and we still didn’t really have a good accounting of the Folksbiene’s history. We had the book that was put out for the Folksbiene’s fortieth or fiftieth anniversary; it was all in Yiddish, I went through it all, and I was able to piece together which were the first plays that we’d done. Eventually I made a spreadsheet of every play, what year, the director, the playwright, anything I could find out about the play. The first play that the Folksbiene did turned out to be “An Enemy of the People” by Ibsen, translated into Yiddish, the Folksfaynd. One thing I noticed was that you see women’s names among the directors in the early part of the Folksbiene’s history, but the only plays we’ve ever done that were written by women were two plays and one review in 1998, ‘99, and at first I didn’t even notice them. We’ve done very few plays by women. First of all, I thought to myself: why? Why are there so many directors, but not playwrights? I started to wonder, were there women playwrights at all?

SG: How did you come to curate the Yiddish women playwrights festival?

SB: First of all, I looked at the Digital Yiddish Theatre Project website and I found your project, Plotting Yiddish Drama, and I found one play by a woman there [SG: Der foygl fun geto, the first synopsis of a play by a woman included in PYD; there are now more]. I went to the National Yiddish Book Center’s Spielberg Digital Library, searched for dramas, got the list, and looked for women’s names. I was just doing it all on my own, as a side part to this Folksbiene history. Then I presented it to my supervisors and they thought it was a good idea, but this was pre-COVID and we didn’t know how we were going to do it, how we were going to have readings, and how we were going to pay for it. But they liked the idea of having a festival of some sort. I suggested that we do it over the course of a weekend or a week and just have a company of actors do all four readings, in addition maybe we could have an academic seminar and invite people to come and present papers about Yiddish women’s literature. That was one way, or spread it out over the course of a season or two, which is how we’re going to end up doing it, because of COVID.

I downloaded and transliterated all the plays, and began translating. I’m not a writer. And my Yiddish is good, but not great. It takes me a long time to translate. I have native Yiddish supplemented by four intensive programs, but they were in the ‘80s, the early ‘80s. My Yiddish reading is much better than it was before I started the project.

Der foygl fun geto was severely cut. The settings can be two or three paragraphs long, it’s very novelistic as a play. If you download it from the Yiddish Book Center, it’s an amazing read. It’s as if you’re reading a novel. I’m not so sure Chava imagined that this would ever be staged. When I first submitted it in my proposal to the higher ups, I said, if we were to do this as written, it would have to go over a period of maybe two or three nights. It’s worth taking a look at, but what we present was a cut, it was a severe cut that Goldie [Morgentaler, Rosenfarb’s daughter] did with Chava’s approval. It was cut when Chava was still alive. I had a meeting with Goldie when she was in New York and was hoping she would give her blessing to doing this, and she gave us carte blanche in that she couldn’t have been more helpful; anything that we wanted to do, she was game for it, which made this whole process much easier. This morning she forwarded me all of the emails that she got from her list of friends, and I can tell that it just means so much to her to have her mother’s work seen by so many people. My mother left Łódź four days before they made the ghetto. Her story could have easily been Chava’s story, or worse. As a kid of Holocaust survivors, it means a lot to me as well.

SG: What are some of the considerations that you took into account in designing the digital reading, did you have much involvement in that?

SB: Our process in the Folksbiene, and it has been for at least since Zalmen became the Artistic Director, is that we never do plays without doing the reading before an audience first. We don’t just get a script and say we’re going to do a full production of it, we didn’t even do that with The Sorceress, which was Goldfaden. I wasn’t involved that much in the actual production. What’s interesting was that we could use actors from all over the world if we wanted to. And we had actors in different places. All the scenes were done by Zoom, all the directing was done by Zoom. But the difference with doing it on Zoom is that our audience can be so much bigger. We had thousands of people see this production. Even if we sold out the theatre for the readings, we would have had to fill the theatre full four times to get 1,200 people to see it. This way, over the course of four days, we got thousands of views and we raised money for Self-Help. I think Director Suzanne Toren and Motl Didner (our Assistant Artistic Director who is also in the play) did a really good job dramatizing the play on Zoom, so I was really pleased with that. I would love to see that play really be done as a mainstage production but that’s above my pay grade. We’re kind of booked for a couple of years because stuff that we were planning to do over the last year and a half hasn’t been done yet, so we have plenty of time to decide.

SG: What are you hoping that audiences took away from Der foygl fun geto?

SB: Number one, that Chava Rosenfarb is a really great writer and she should be read more and people should look her up and read the translations her daughter Goldie did of her works (and Chava was involved in the translations herself). Also, to see the quality of Yiddish playwriting, that it’s not all melodrama, but this was a serious play about a serious moral dilemma that this author lived, not in Vilna, but in Łódź. It was her imagining of what was happening in Vilna based on her experience in the Łódź Ghetto. I want to show that there are women playwrights as well as poets. All of the Yiddish classes I ever took that had women writers just taught poetry. And I want, in the broader sense, to show that the breadth of Yiddish literature is deeper than we thought. I want to show that the Folksbiene can do Yiddish works that aren’t Fiddler on the Roof. Working on the Fiddler production was one of the highlights of my life, but I want to take the Fiddler audience that said, “oh, I can read subtitles during this show,” and say “okay, I can go and watch a serious drama and get something out of it as well.” I want to expand the audience for Yiddish dramatic literature, because we have done a number of lighter works that were audience-friendly. And as a feminist who grew up with, and was a beneficiary of, the women’s movement, I want to bring that into our organization.

SG: What are you most looking forward to in the upcoming readings in the festival? Are there particular plays or themes that you’re especially excited to see staged?

SB: Well, I love Kadya Molodowsky and I can recite “Di dame mitn hintl” (The Lady with the Dog) from memory from when I went to Yiddish summer camp. In fact, she came to my camp in my first year, when I was seven, and I remember, we were all preparing for Kadya Molodowsky and it was a big deal. I had no idea who she was, of course, but we learned all these songs and for some reason I know this long children’s poem, so I’m looking forward to Ale fenster tsu der zun (All Windows to the Sun), which is a children’s play largely in verse. Then Miriam Karpilove’s In di shturem teg (In Stormy Days) speaks to me because I grew up in a Bundist family and the play is a Bundist play, it has a lot of Bundist songs in it. It revolves around the political tensions in 1905. I’m personally very excited about that, as I still consider myself a Bundist. Marie Lerner’s Di agune (The Chained Wife) is interesting because, as far as I understand, it was the first produced Yiddish play ever by a woman, in the 1880s. For historical reasons I’m excited about that. I’m enthusiastic about all of the plays that are on the list so far, and I’ll be looking to expand it, I see no reason this festival can’t just go on and on and we stage whichever plays are the best.

SG: That sounds fantastic. What have you learned about Yiddish women playwrights in the course of creating this festival, and what do you hope other people will take away from it?

SB: Well, first, that there are Yiddish women playwrights. Two, that they’re as good or better than male playwrights. I would match the ones I’ve read against the vast majority of the male- written plays that I’ve seen or read. If the women’s angle brings some people into reading or learning about Yiddish literature because they’re interested in women’s studies or feminist studies or gender, that’s also a plus.

I’m working for a theatre that’s 106 years old, it was started by workers (Workmen’s Circle branch 555 [the organization now called Worker’s Circle]), we’re the oldest continuously-producing Yiddish theatre in the world, and maybe one of the oldest producing theatres in the United States (there’s a little bit of competition on that). We were started in 1915 and we’re still here. I want the Folksbiene to remain a Yiddish theatre, I want to continue that as long as possible. I don’t think anyone would have thought that in 2021 Yiddish theatre would still be put on in New York at a high professional level. And we weren’t a professional theatre for the good part of our history. Workers would come in after a day at the sweatshops and do whatever had to be done, and now we have professional actors and professional directors and set designers and we’ve won Off Broadway awards, not just for Fiddler. When I was a kid, and they took us to the Folksbiene, I wouldn’t have imagined that 40, 50 years later it would still be in existence, because the “Yiddish is dying” trope was around then, in the early 70s, and “there’s not going to be anyone to speak Yiddish” and “isn’t it cute that you speak Yiddish and sing a Yiddish song,” and now I look at Zisl Slepovitch’s daughter [Dinah] when she’s singing and I feel the same way they felt when they saw us singing Yiddish songs. Yiddish is my Jewish identity. To me, being a Jew, is really the Bundist motto, being politically aware, not needing Israel as the center of my Jewish identity, and not being religious. It’s this cultural richness that ties back to the thousand years of Yiddish speakers. That makes me Jewish. I think it’s kind of amazing that those of us who can are doing everything we can to let other people know about it and to keep it alive. I always say it’s like the Godfather II, “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!” I always end up back in the Yiddish world somehow.

Article Author(s)