My Path to the Yiddish Theatre: David Edelstadt’s Revolutionary Recitation

Bella Bellarina was born in Warsaw on July 15, 1898, into the legendary Rubinlicht family, known for the intellectual and cultural accomplishments of its worldly children. Her father, Getzl Rubinlicht, was a real estate broker, while her mother, Tune attended a girls’ school. In 1916, she enrolled in the Warsaw School of Drama. There, Dovid Herman, future director of the famed Vilna Troupe, saw her perform and urged her to join several drama clubs in Warsaw. In 1918, she became a member of the Vilna Troupe and toured with them across Europe for several years. In 1924, the company arrived in New York, where Bellarina decided to remain, together with her husband and fellow actor Haim Schneyer Hamerow. Bellarina and Hamerow continued to tour for several more years with various Yiddish theatre companies throughout North and South America. Much of the Rubinlicht family remained in Warsaw and was killed in the war. Despite the decline of the Yiddish theatre in the postwar period, and despite never transitioning to the English-language stage, Bellarina continued to appear in benefit performances and other cultural functions. Haim Hamerow died on July 24, 1961, and Bella Bellarina on February 1, 1969. Bellarina’s autobiographical account, “My Path to the Yiddish Theatre: David Edelstadt’s Revolutionary Recitation” appeared in the Yiddish newspaper Fraye Arbeter Shtime1 and details her first childhood exposure both to theatre and politics through her beloved older brother Fishl and his revolutionary leanings.

This piece was translated from the original Yiddish by Sandra Chiritescu.

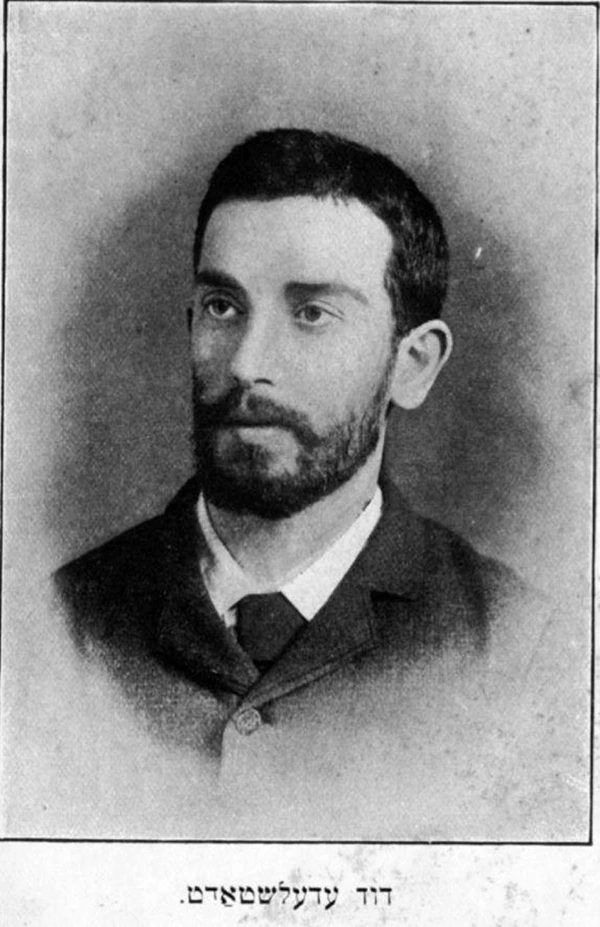

My first recitation in Yiddish was David Edelstadt’s “The Fall of the Bastille.” How did I, a Hasidic girl, a daughter of such pious and religious parents, encounter such a revolutionary poem? It is thanks to my older brother, Fishele, who was then a young boy of fourteen or fifteen in a long caftan. Later, he was known as the famous sculptor Felix Rubinlicht; he died a martyr, in the Sanctification of the Name.2 Fishele was my first teacher and my first director. He taught all of us children, a gaggle of—no evil eye!—altogether twelve siblings, to sing David Edelstadt’s3 “O! Good Friend When I Will Die!” and “O! Muse Don’t Wake Me with Your Magic Fingers! Don’t Wake the Strings of My Ill Heart!” and “You Fell Dead and Closed Your Eyes Forever.” We sang these songs with so much soulfulness. My childish heart would hurt especially when I heard the line: “The pale singer is sentenced to death, the poem about struggle and pain is over.” Why?

Through our open windows, the songs would burst forth into the courtyard and soon the other windows would open up, too. The neighbors would catch on to our songs and sing with us, at first a little timidly and not too assuredly, but soon more strongly and more loudly. The whole courtyard sang together! Saturday afternoon when everything was quiet at home, our father was away at the Gerer shtibl,4 and our mother would lie down for a nap. We children gathered in the kitchen, and Fishele read to us those “forbidden” books and lead us far astray into the worlds of struggle! Heroes, high ideals, love for people…

He secretly brought the books from his revolutionary circle, also journals and brochures from afar, all the way from the United States! For this purpose, we used to give Fishele our collected Hanukkah money and all the going-away gifts that our wealthy uncle Abraham R. from Kutno gave us so generously, a silver coin or even a bill worth twenty. It was worth it! We held our breath as we devoured books by Victor Hugo, Kropotkin, Tolstoy, and Gorkii—they were our close acquaintances, frequent guests in my father’s kitchen after the tsholnt and kugl.

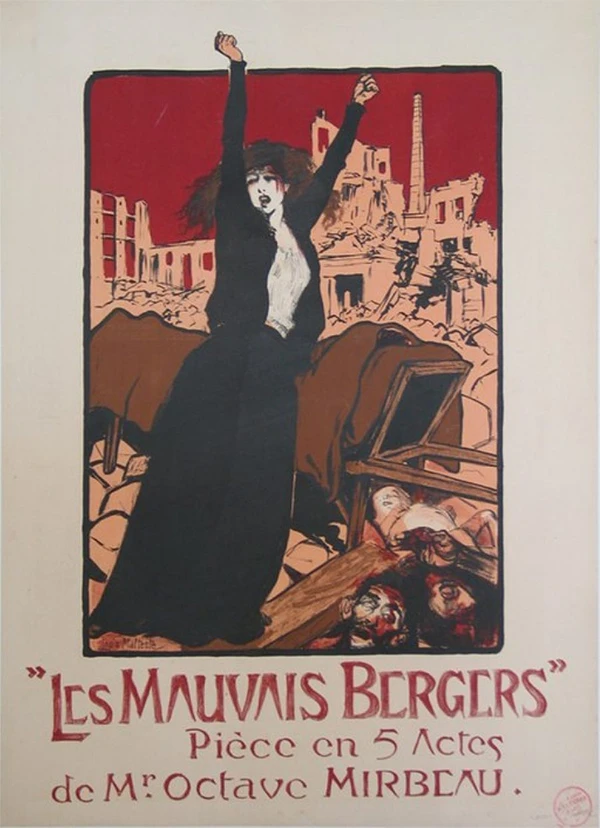

Fishl even confided in us a secret: that he had snuck into the Yiddish theatre for five kopecks to Kampaneets5 on Muranow Street. They were putting on a play about the French Revolution, John and Madeleine, by Mirbeau.6 I listened with wide-open eyes and a racing heart as he reenacted the last scene where the heroic Madeleine comes up against the barricades together with her lover John: “For freedom, down with the tyrants!” he finished with pathos, and ignited a revolutionary fire in our childish hearts.

I don’t know why he picked exactly me to recite David Edelstadt’s “The Fall of the Bastille.” Did he feel even back then that among all of us children I would be the only one to grow up an actress? Or maybe the opposite, because of this recitation I became an actress? I only know that I became very frightened. “No, I’m afraid I’ll forget” (but quietly in my heart I was proud). “You have nothing to be afraid of, I’ll prompt you. But you have to speak with all your heart and loudly so that everyone can hear.” We began “rehearsals” every evening, starting in the afternoon at 3 or 4 o’clock when it became a little quieter at home after the big hoo-ha. The racket subsided and the winter nights fell early. My director and I would sneak into the big dining room in the middle of the house, position ourselves and begin our “rehearsals.” “Do you hear the thunder, storm, and noise?” I would call to the world with so much childish fire in my heart that I didn’t see what was happening around me.

Every Thursday evening, Mindl the Fish Peddler would bring fish to our home for Shabbat. I can still see her before my eyes. My heart still aches for her and her tough luck, for how she toiled for a paltry piece of bread. On her shoulders, she used to carry two big buckets of water to bring the few live carps into the homes of the wealthier housewives. She was wrapped in an old shawl with a torn scarf on her disheveled hair and three to four skirts, one layered over the other. They were wet with pieces of ice; entire icicles were dragging along at the hems. She wore two big men’s slippers bound with some rags. I can still see her two frostbitten hands before my eyes, red and bloody with cracked skin.

The fish were always half-dead because there wasn’t enough water in those two buckets. My mother always complained that they were dead and that she wanted live carps for Shabbat. “Madame, the fish are alive! What are you talking about? They are wriggling, I only wish my children moved as much, God Almighty!” Mindl would swear. My mother nonetheless shook her head “No” and Mindl would resort to her last argument: “Madame! Buy something from me, I need to send the children to kheyder.” And that immediately had its effect. My mother paid, and we soon saved the fish by pouring a little liquor from my father’s carafe into their small, gaping and languishing mouths. It worked like magic. The fish began to wriggle, dance around, and jump like old drunkards. The mitzvah to have live fish on Shabbat was always fulfilled.

On that Thursday evening, I recited with such enthusiasm “you hear the thundering, the people are making a racket, they have realized their great power! Tyrants, you are lost! You must flee from your wealthy palaces! Hurrah! Down with Nikolai!” Suddenly, we heard Mindl yelling in the dark and clapping loudly with her hands. The two buckets fell down and water spilled all over the polished floor. The freed fish began to wriggle like “revolutionaries” with such force that I truly thought the Bastille was falling. “Madame! We are going to kill the Tsar!” My mother came running startled and pale, and oh well…she gave me a good talking to.

But I couldn’t take my eyes off of Mindl. Somehow, she had grown taller with gleaming eyes, her face glowed, and she had both her hands up in the air ready to go to the barricades, just like the heroine Madeleine. Yes, that was my first audience, the clapping of her bloody hands the biggest applause of my life. And I felt in my heart that my fate would connect me to all such poor, deprived, wronged people, to all the Mindls of the whole world. I will serve and help them until the song of my “Pale Singer” will come true: “Man is born for freedom, and for love; let freedom rule the world.”

Notes

- A version of this memoir appeared in the Yiddish daily Fraye Arbeter Shtime on July 31, 1953.This excerpt was taken from the manuscript copy of Bella Bellarina’s memoir that is located in an archive in her name, RG 574 at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

- Sanctification of the Name (or in Yiddish, kidush ha-shem) is the concept of dying for God and here refers to his murder during the Holocaust. Little survives of Felix Rubinlicht’s pre-war artistic output. However, he was the designer and sculptor of the imposing monument on the grave of the famous actress Esther Rokhl Kaminska, whose autobiographical writings are excerpted in this volume.

- David Edelstadt (1866–1892). In 1890, he became a regular contributor to and, a year later, editor of the newly founded anarchist weekly Fraye Arbeter Shtime.

- A shtibl is a small, Hasidic house of prayer. Ger (or Gerer when used as an adjective) was a particular dynasty of Hasidism whose leaders originated from the town of Gora Kalworia.

- A reference to Aba Kampaneets’ theatre troupe. See Zalmen Zilbercweig, Leksikon fun yidishn teater., vol. 6 (New York: Elisheva, 1931), 5415–32.

- Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917), Les Mauvais Bergers (Paris: Librairie Charpentier et Fasquelle, 1898).

Article Author(s)

Sandra Chiritescu

Sandra Chiritescu is a PhD candidate in Yiddish Studies at Columbia University and pedagogy and blog editor at In geveb: A Journal for Yiddish Studies.ll them who the author is ect.