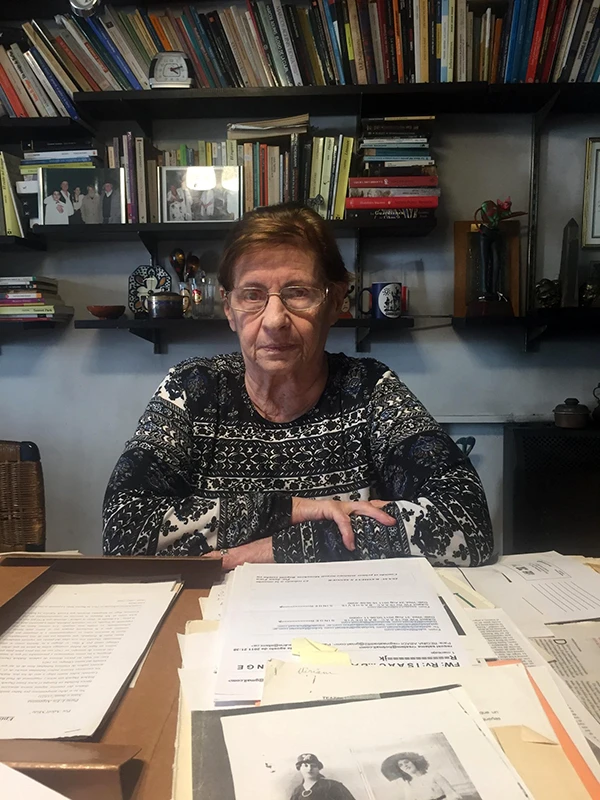

Rosa Rapoport and Teatro IFT in Buenos Aires

Rosa Rapoport grew up alongside Der yidisher folks teater (Jewish People’s Theatre, also known as Teatro IFT), the first independent Yiddish theatre in Buenos Aires. In this excerpt from Rosa’s oral history, she shares her memories performing on stage at Teatro IFT, and the theatre’s eventual transition from Yiddish to a Spanish-language repertoire.

DYTP member C. Tova Markenson, a doctoral candidate at Northwestern University conducting research for her dissertation on Yiddish theatre in Latin America, recently interviewed Rosa about these experiences. In this excerpt, Rosa shares her memories from the 1950s. Tova conducted the interview in Spanish and translated it into English.

We were saddened to learn that Rosa Rapoport passed away on March 12, 2018, before she was able to see the final version of this interview. Today, April 11, 2018, is Rosa’s shloyshim, the 30 day anniversary of her passing. We hope that the memories of her life that this interview captures serve as blessings for all who knew and loved her.

Rosa Rapoport: My name is Rosa Rapoport. I’m the daughter of a woman who was an actress in Teatro IFT.

CTM: What was your mother’s name?

RR: Eva Vaserman. She was also one of the founders. I was always known as Rosa Vaserman when I acted in the theatre. I was born in Buenos Aires and I’m not so young anymore, I’m eighty-one years old. I participated in Teatro IFT for many years, for thirty years. I was an actress for Teatro IFT starting when I was very young, because my mother was in the theatre. After that I worked for just a few years outside of the Teatro IFT, but after that I abandoned my theatre career and I got a degree in history.

I am a teacher of social history. I work principally with older adults. I teach history classes, and it is incredibly lovely this kind of work, it’s just incredible, because the people who come are history. At one point or another I got interested in doing research on the history of Jewish theatre, in part because I was part of the Jewish theatre. Since I was a witness to it, I don’t just tell stories about it, I tell what I saw, and what I know, above all about the actors, the quality of the actors that there was, and the kind of actors that there were.

CTM: How was it that you learned to act?

RR: I went to the IFT with my mom, who went there a lot and knew a lot, and the IFT had a theatre school. When they organized the theatre school, I went to the theatre school. I was fourteen years old. It was a long time ago, so there is a lot that I don’t remember.

I do remember that we studied various subjects, there were many more cultural subjects than artistic. We studied the Yiddish language and Yiddish literature, some philosophy, calisthenics, voice lessons, and there were acting classes. Not in Stanislavski’s method, Stanislavski had not yet arrived on these shores.

This group met in the theatre school, and after that we became part of the ensemble of Teatro IFT, and after that we were the directors of the Teatro IFT. It was a pretty large group. One of the people I met there later became my husband, Manuel Iedvabni.

CTM: What kinds of performances did you put on in the theatre?

RR: First we participated in the performances of the IFT as extras in mass scenes. Because in previous eras, when there was more money to make theatre, performances had “mass scenes.” Today they do the same with projections and the like. These were our first experiences on stage. This was the best experience for our theatre education, because it permitted the youth to come into contact with experienced actors, and with the mystery that surrounded the IFT and its stage.

After that, each one of us took on small roles, and later ones of greater importance. Not all of the people in this group were actors—many were directors, others were designers, others were musicians—but we always participated in the works of the IFT. Eventually all of us at some point—for circumstances relating to the organization and of life—we all left to make our artistic life elsewhere.

I’ve done some research on the IFT and on theatre in general. What I want to tell you about is that there were two strands of theatre that almost did not cross. Or they very rarely crossed, because one was theatre in the Yiddish language, whose objective was commercial theatre or professional theatre.

On the other hand, the IFT was always an independent theatre with its own objectives. Even though its objective was to be a professional theatre of paid actors, still its structure and its ideology was an independent ideology.

The IFT had a repertoire not only of long works, but also of shorter works, because smaller groups of actors traveled throughout Argentina, including the provinces, the agricultural colonies where there were Jewish colonies, performing theatre. My mom worked in these various itinerant groups. And it was extraordinary work, marvelous, because it was bringing theatre to places that were in the middle of nowhere, it was a really beautiful thing.

CTM: Can you say more about the IFT’s transition from performing in Yiddish to performing in Spanish?

RR: Look, the IFT used to be a Yiddish-speaking theatre. It started in 1932, and in the year 1940 or 1945 the Jewish community had more or less between 500,000 and 600,000 people. It was a community that was large, a community with many layers, growing in its economic aspects but with a strong Jewish working class that spoke Yiddish, and separate from that which was educated. Humble people from European countries with a lot of cultural anxieties. It was people like these who were the founders of the IFT, the initial ensemble that was so, so important, and I had the privilege of seeing it. In the 1950s and 1960s people started leaving the IFT, for a variety of reasons, and after that the majority of them stopped acting, some of them performed a little bit in the professional Yiddish theatres, but for a very short time.

The IFT had a political and cultural legacy that was very, very strong and well developed up until the 1950s. At this point, there was already a second and a third generation that didn’t speak Yiddish anymore. They understood Yiddish, but they no longer spoke Yiddish. They considered themselves Jews, and they considered themselves part of the community, but theatre in Yiddish did not appeal to them. However they were interested—and this continues up until today—in going to plays about Jewish themes, but in Spanish.

This was an incredibly difficult moment, with much internal debate as you can imagine, and with great pain for many people, above all the founders of the theatre, the creators of the theatre, but reality intervened.

The first play that they performed in Spanish was The Diary of Anne Frank in the year 1957. It was not only a phenomenal success but also a work of incredible emotion. Because it was the The Diary of Anne Frank, because the discovery of The Diary of Anne Frank was all around the world a moment of incredible emotion, and because it was in Spanish, and because the entire Jewish community—young people, older people—everyone went to see it.

Almost at exactly the same time, Joseph Buloff performed it in Yiddish in Buenos Aires. And the person who played the role of Anne Frank in that production, Ilita Eisenberg, was an actress that came from the IFT. She left the IFT and started working in the professional theatre. This was a very powerful and important moment in the development of the Teatro IFT, and for the community. To be able to see such a beautiful work.

CTM: Did the Jewish community go to see both performances? Both in Spanish and in Yiddish?

RR: I don’t know. I think that those who no longer wanted to see Yiddish theatre didn’t go, but everyone went to the IFT. Because it was in Spanish, of course. Politics is very much mixed in to the history of these two types of theatre.

Here there are many political debates that are very fierce. They aren’t debates, they’re political ruptures. Some of the institutions of the Jewish community made a kherem to the IFT. Do you know what a kherem is? Excommunicated. The IFT was a theatre of the left. More or less, the IFT maintained relationships with the rest of the community. In reality, the kherem did not work. It doesn’t exist anymore, but the division continues.

For this reason the debut of The Diary of Anne Frank was so strong, and it was so important that the entire community went, because the communal institutions had prohibited going to the IFT, but everyone went to The Diary of Anne Frank.

The world moves in such a strange way.

Article Author(s)