Why Does Muni Weisenfreund Play “Shund”?

BY ALEF ALEF [Ephraim Auerbach]

Translated by Zachary M. Baker

Translator’s note: This interview was published in the short-lived New York Yiddish daily newspaper Di tsayt (Die Zeit = The Times), October 29, 1921. That autumn, Muni Weisenfreund was performing at Joseph Edelstein’s Second Avenue Theatre, following two seasons with the Yiddish Art Theatre, where the young actor had his New York Yiddish debut. There, under Maurice Schwartz’s direction, Weisenfreund was assigned minor roles in what critics referred to as “the better Yiddish repertory,” i.e., plays considered to be of higher literary merit than the “shund” operettas and melodramas that were standard fare at the other Yiddish theatres. Weisenfreund’s breakout role at the Yiddish Art Theatre came in October 1920, when he played the Russian student Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov, in Sholem Aleichem’s play “Hard to Be a Jew” (Shver tsu zayn a yid). In his review of the play, Abraham Cahan, the longtime editor of the Yiddish Forward, wrote, “Two things remain deeply etched in the theatre-goer’s memory: the play itself and Weisenfreund. It would be difficult to imagine the play without this young artist…. It’s a shame that the [late] author could not see this production of his masterpiece, with Weisenfreund as Ivanov.”1 During his years on the New York Yiddish theatre scene, Weisenfreund moved back and forth between the Yiddish Art Theatre and more commercial venues like the Second Avenue Theatre. As this interview attests, his preference was to perform in the more literary plays, but contingent factors did not always make this possible. Weisenfreund eventually made the transition from the Yiddish to the American stage – and from there, to Hollywood, where as Paul Muni he became a major star and was nominated for several Academy Awards. He won the Oscar for Best Actor in 1936, for his performance in “The Story of Louis Pasteur.”

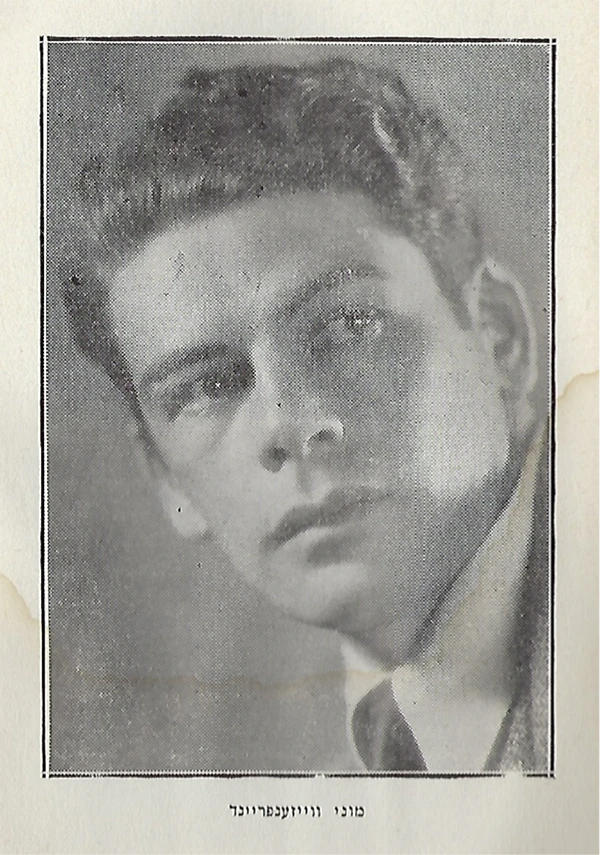

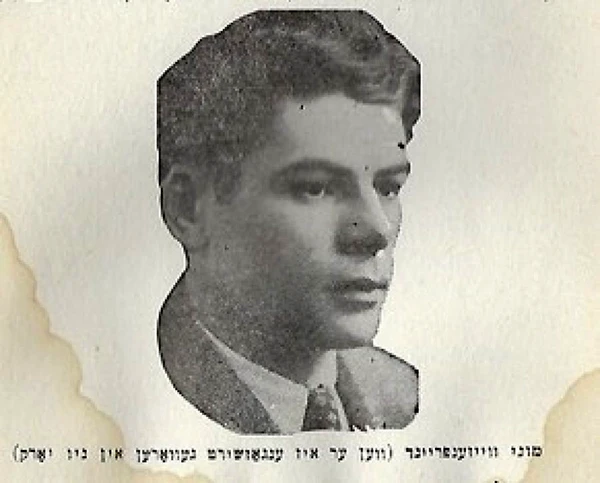

The career of the young actor Muni Weisenfreund is noteworthy, practically legendary. Just two years ago he was completely in the shadows; he was an unknown, even to his actor colleagues. And now he occupies a respectable position on the Yiddish stage and, more significantly, his emergence has come about exclusively through the better Yiddish repertory.

Two winters ago, Maurice Schwartz hired him for his Irving Place Theatre, and his first role was Zazuli the village scribe in Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye the Dairyman. A small, trivial role, Weisenfreund was on stage for no more than a few minutes, and yet he managed to create an original character type. Right then and there, the young actor—whose name was completely unfamiliar to the critics and the public—attracted everyone’s attention, even though all of the other actors’ performances were outstanding.

With each new role, Muni Weisenfreund has matured as an actor—and exclusively in serious roles; he is a character actor possessing immense talents. Last year, Muni Weisenfreund achieved his greatest degree of favor among sophisticated theatre-goers with his performance in Sholem Aleichem’s Hard to Be a Jew, as the Russian student Ivanov—who as a prank becomes a Jew.2 Ivanov became the central figure in the play and Muni shaped the role out of his own imagination, making it a completely original creation.

I did not conduct an interview with Muni Weisenfreund, strictly speaking. Even though I had all of my writing tools poised for action, my pencil and paper sat untouched on the table because it is hard to take notes when a person speaks to you with such sincerity. Just imagine how foolish it would seem if, while your friend pours out his heart, you constantly interrupt him with, “Wait, I need to jot this down!” You can’t describe the human heart in all its fullness (as opposed to conveying solitary utterances) through the kinds of brief jottings that an interviewer ordinarily takes down.

Why has Muni Weisenfreund gone over to shund? Certainly not for the money—and emphatically not because he finds the shund plays appealing. The tone of his voice, when we spoke, testified to the fact that he is devoted to the better Yiddish repertory and is prepared to serve it, irrespective of any sacrifices that this might entail for him. He feels guilty to be sitting before me like a sinner who pleads for understanding and, to be sure, forgiveness. It was only an unfortunate contingency that diverted him from the happy path that he had embarked upon at the beginning of his career.

The unhappy circumstance belongs to a sequence of theatrical muddles in which Weisenfreund himself is the least culpable party. But he reassured me that no future such happenstances will be able to influence the trajectory of his acting career. Henceforth, regardless of the conditions, he will remain faithful to the better Yiddish repertory. I believed him because he is the personification of sincerity. He opened his heart to me: “It’s very bad when an actor who wishes to perform in a serious theatre has a limited terrain in which to do so. We have only the one Yiddish Art Theatre, and the actor who is determined to join its ranks must bend and accept all manner of compromises.”

Now, Weisenfreund hasn’t the least pretensions toward stardom. He is modest, as only an honest artist can be. He wants only one thing: to have the possibility to be creative – to devote his talent to the pure dramatic arts. I believed him when, in the course of our conversation, he said with his characteristic sincerity, “I’m not chasing after any major roles; I don’t particularly want to play the main characters. Give me the smallest role, where I appear on stage for just a few minutes, but I want to play a human being, someone with a vibrant soul. Take Peretz’s Golden Chain (Di goldene keyt), where I played the role of the flax merchant. I was on stage for a grand total of five minutes and I was satisfied; my artistic ambitions were largely fulfilled in that role. And although I played such a marginal character, the critics acknowledged me, and the public noticed me. I can reassure you, I’m not chasing after money or my picture on the posters. For me, the main thing is to perform, to create a human type on the stage.”

Last season, Weisenfreund performed with Maurice Schwartz, who was still partners with Max Wilner at the Irving Place Theatre. Schwartz taught him that in a good play, one that is put on by an art theatre, the length of a role needs to be disregarded; rather, each actor plays the role to which he or she is most suited. And for that, Weisenfreund is grateful to Schwartz. He doesn’t know whether Schwartz still fully accepts that premise, but he himself definitely does. And when Weisenfreund once again has the opportunity to play at an art theatre he will convince those who doubt his sincerity.

At the Irving Place Theatre, the frictions between Wilner and Schwartz had begun, and the latter declared that he was not going to remain in New York. Schwartz said he had an opportunity to perform his plays in the provinces and was going to take advantage of it.

Weisenfreund believed him, and because he felt that in any event the Irving Place Theatre was not going to stick with the better repertory (several times, Wilner told him and his fellow actors that he was going to put on operettas and melodramas) he permitted himself to be persuaded to be hired by Joseph Edelstein and perform in his theatre. However, he left the door ajar; were Schwartz to call upon him, he would be free to come and perform the better dramas with him.

When Schwartz got wind of the fact that Weisenfreund had already been engaged by the Second Avenue Theatre, he let it be known that he had leased the Garden Theatre and wanted to claim Weisenfreund. And the latter told him, “I want to perform with you and will accept twenty-five dollars a week less, but you need to speak with Edelstein and tell him that he should release me. He will definitely do so if you discuss it with him.”

So, Schwartz went to Edelstein, but he went on in such a way that Edelstein opted not to free up Weisenfreund from his contract. The conversation between Schwartz and Edelstein proceeded more or less as follows:

Schwartz: Mr. Edelstein, will you release Weisenfreund to me?

Edelstein: Do you really need him so badly?

Schwartz: Well, you know, in an ensemble he’s not such a bad little actor.

Edelstein: In that case, I won’t release him to you because to me Weisenfreund is not a “little actor.” I took him for the main roles and will hold onto him.

Schwartz couldn’t offer any further arguments to counter that point, and so he departed. Greatly annoyed, Weisenfreund remained with Edelstein. He performed in “The Russian Princess,” albeit under strong protest – and even though he managed to accomplish something in the role. To this very day he remains extremely dissatisfied with himself in “Hello, Shmendrik,” and was absolutely incapable of accomplishing anything with it, so in the end the management decided to let him off the hook. He is pleased with that and hopes that in future he won’t have to play any silly roles: “This is the last season that I will perform in these types of plays, even if I have to sacrifice much of what I’ve achieved. I feel guilty, even though I’m not guilty.”

Weisenfreund related a lot of interesting details to me concerning his career as a performer. Here, I will convey just one incident that is characteristic of the young actor.

When Schwartz began to apportion the roles for his production of Sholem Aleichem’s Hard to Be a Jew, after a lot of give-and-take Weisenfreund was assigned the role of the Russian student Ivanov. However, the actor took fright because he felt that he wasn’t suited for the part, since he is merely a character actor and not a romantic lead type.

Weisenfreund exerted every means to get out of the role, but Schwartz wouldn’t budge; with his experienced directorial eye he sensed that Weisenfreund would make something of it. So, the actor approached Sholem Aleichem’s son-in-law, I. D. Berkowitz, asking him to prevail upon Schwartz to take away the role from him. The day before the premiere, he pleaded with Berkowitz, “Have pity on me; this role is not for me; take it away…”

Yet, in the end Weisenfreund elevated the role to the very highest artistic plane.

Article Author(s)