Yiddish Opera at the Standard Theatre, London 1895

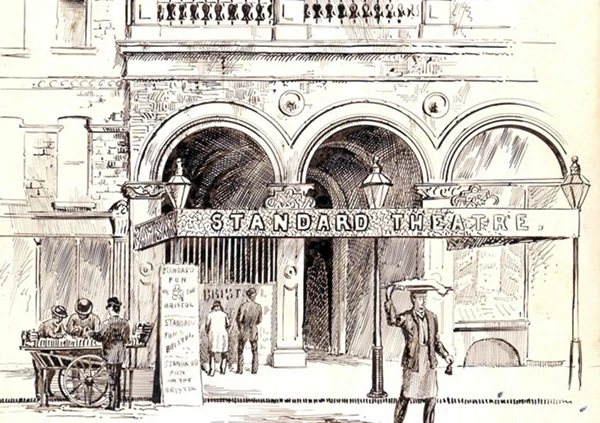

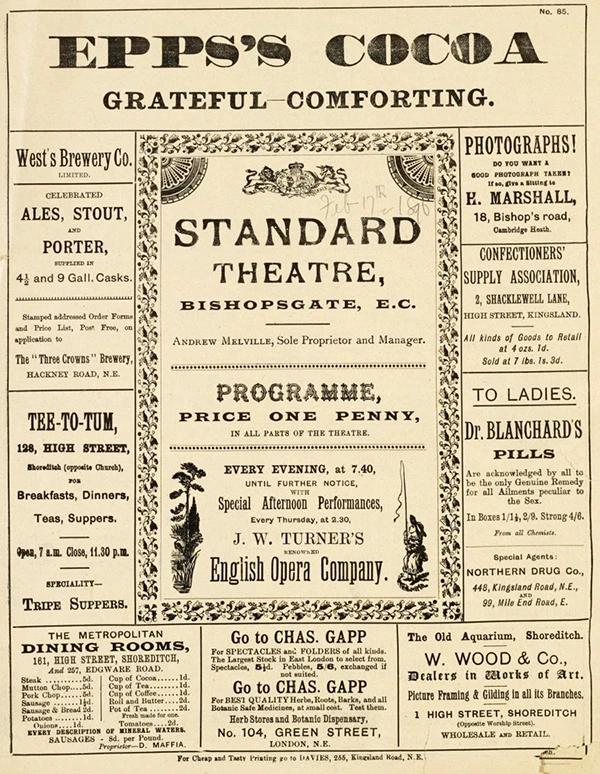

Spanning almost four centuries and more than 11 million of digitized pages, the online newspaper collection of the National Library of the Netherlands is full of surprises. While looking for reports about the first screenings of the Lumière cinematograph in Paris, I stumbled on a story about a Yiddish opera company that was performing in London in December 1895. I was intrigued by the title and the fact that the review was published in a newspaper for the Dutch East-Indies (today’s Indonesia). Who in Surabaya would possibly be interested in reading about Yiddish theatre in London’s East End? I won’t attempt to answer that question, but I do like to share what the writer tells us about what is probably one of the first Yiddish performances at the 2400-seat Standard Theatre on Bishopsgate.

The article was written by J.T. Grein (1862-1935), a prominent Anglo-Dutch theatre critic and impresario, who was one of the founders of the Independent Theatre Society in London in 1891. Throughout his career, Grein regularly wrote about the Jewish stage. In the early 1920s, he extensively covered the rare visits to London of the Vilna Troupe, and he was strongly involved with the Jewish Drama League. Grein may well have developed this life-long interest from his first encounter with Yiddish drama in London’s East End in 1895.

Grein knew the East End quite well. In the early 1890s, he published several short stories about the quarter and its poor. Walking in Aldgate in December 1895, he was nevertheless surprised to see big posters in Hebrew letters and smaller ones in English announcing a series of Yiddish performances by the Oriental Operatic Company.

I don’t need to explain to you that I was looking with big eyes at the posters – great Hebrew operas, sung by Jews, composed by Jews, performed in a Jewish neighbourhood – this was so unique that I just had to be there, even if the performance started already at 7.45, which would force me to dine in the City. And what that means, only a true “West End-man” knows.

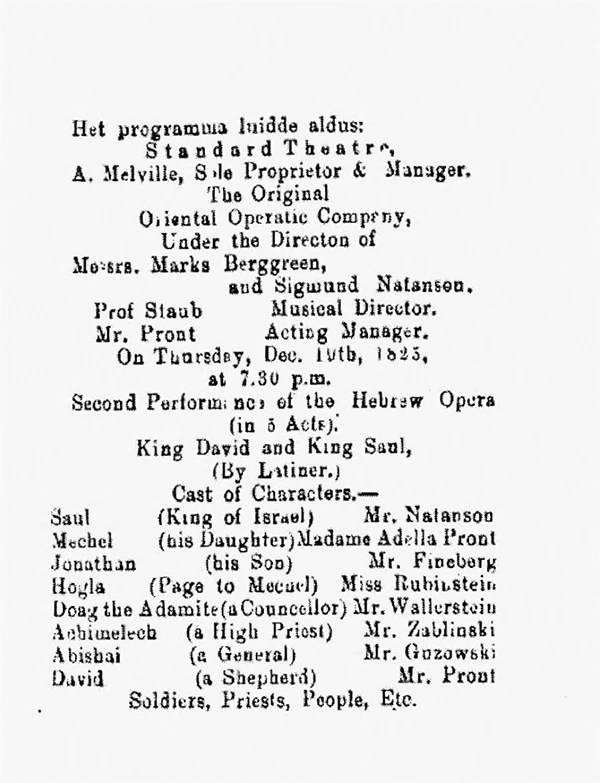

Four plays figured on the bill: “Rabi Yoselman, the liberator of Israel – major Hebrew Opera by A. Goldfaden,” “King David and King Saul by Latiner,” “King Pharao,” and “Sulamite-Bethlehem’s Daughter” (more likely Goldfaden’s popular Shulamis or The Daughter of Jerusalem).

Grein went to see the Lateiner play with a journalist friend. We get the impression from his account of the evening that he felt that they were attending a quite special event. He therefore decides to include quite detailed information from the program:

“Perhaps this is a document of some historical value,” he adds somewhat cautiously. More than a century later, we are indeed delighted to find this list of names. It is a pity though that the original handbill did not survive – unlike the program of St. George and the Dragon, the Christmas play that was staged at the Standard a week later. From the surviving evidence, it seems that the director of the Standard Theatre – actor-manager Andrew Melville (1853-1896) – used to program travelling companies whenever he was rehearsing a new play with his own troupe. This gave the small company led by Sigmund (later Charles) Nathanson and Marks Berggreen their first break in London.

What impression did the performance of King David and King Saul make on J.T. Grein and his friend? We have to realize that they were outsiders in more than one respect and must have stood out from the rest of the audience, mostly immigrants from the East End. Neither of them spoke Yiddish and the whole setting was rather exotic to them as middle-class gentlemen. It was a bit like a slumming expedition. This may have added to the excitement. In any case, there is no doubt that the two men had a good evening.

The review centers on the music. Grein particularly appreciated the orchestration and fine singing. He points out that it was the kind of fare that fans of Meyerbeer, Rossini, Mendelsohn, Halevy, Offenbach and Strauss find extremely pleasing. The implication is that he himself has a more ambitious taste, but there is also the explicit acknowledgment that the work is a fine piece in its genre. A fine piece, although not very original.

… the music of the opera Saul and David is a clever mosaic of the most famous arias of Jewish composers, there is no spark of authenticity in it, the ensembles are gaudy, full of fiorituras à la Meyerbeer, the solos are variations on popular folksongs – tunes that catch the ear and strike the sentimental heart.

Grein recognizes many tunes from other works. Evidently, he does not mind this “borrowing,” which was a common practice at the time. Intrigued by the quality of the score, he is asking around about the composer of the operetta. Who is it? Professor Staub – the company’s musical director? The famous Lateiner? Or someone else? He does not get a straightforward answer and decides to just enjoy the operetta like the Jewish immigrants around him. However, unlike them, there is one thing which he hates about the performance: the daytshmerish that is spoken by the actors. This rather bombastic imitation of German was preferred by many actors in the early days of the Yiddish stage, especially when they played royalty or other upper-class characters. As a near-native speaker of German, it was a torment for Grein to listen to this artificial language, which was pronounced with rolling r’s and salted with typical Yiddish words like nebekh and meshuge.

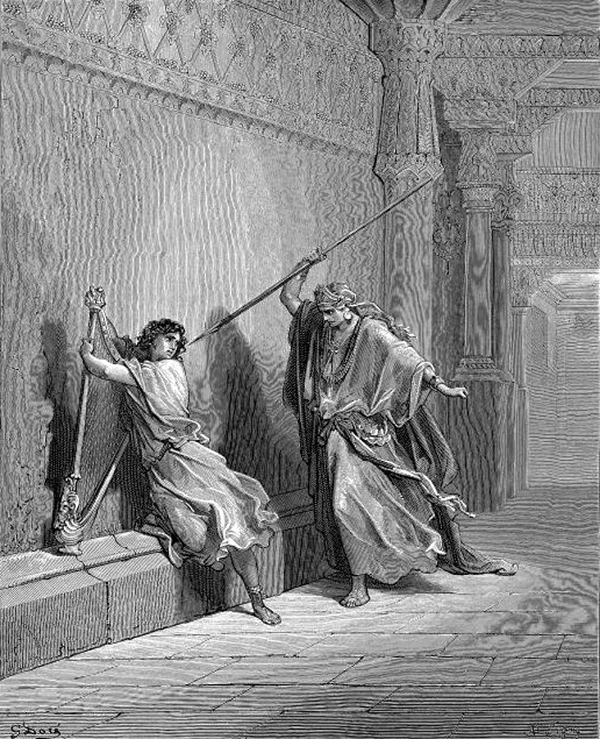

In the article, nothing is said about the plot. Grein probably assumed that his readers were familiar with the biblical story of David and Saul. About the staging, we learn a few things: the decor was sober and in the style of Gustave Doré. Locals – “all of the real race” – were hired as extras to play the soldiers. In Grein’s view, this added to the realism of the scenes. He found it less convincing that some actors were wearing costumes that looked more like Swiss than “Oriental” garb. The troupe probably had used the wardrobe of the Standard Theatre to dress the extras and actors in the minor roles.

Altogether, J.T. Grein’s very first review of a Yiddish play leaves me with mixed feelings. It is more a human interest story than a genuine theatre review. One wonders how he wrote about West-End shows. His tone is sometimes rather paternalistic and patronizing, even condescending. In this respect, his attitude toward popular Yiddish theatre echoes the reviews of shund plays in the American Yiddish press. On the other hand, he was more friendly in his criticism than they were, and clearly found Lateiner’s potboiler pleasing, in particular its music. A final question remains: who was the composer of King David and King Saul? I like to imagine that is was Yankele/Giacomo Minkowski (1871-1941),1 an immigrant Jew from Odessa who arrived in New York in the early 1890s and wrote several scores to Lateiner operettas starring Boris Thomashefsky. The talented young man had changed his first name to Giacomo in homage to the great Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Meyer Beer). And it is Meyerbeer’s influence and tunes that J.T. Grein repeatedly recognizes and enjoys during this first visit to the Yiddish theatre in December 1895.

Notes

- Ronald Robboy gives an overview of his long-forgotten career in “Reconstructing a Yiddish Theatre Score: Giacomo Minkowski and His Music to Alexander; or, the Crown Prince of Jerusalem” in Inventing the Modern Yiddish Stage, eds., Joel Berkowitz and Barbara Henry (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2012).

Article Author(s)