But Enough About Strindberg; Let’s Talk About Goldenberg!

Years ago, while researching the Polish-Jewish painter Maurycy Minkowski’s 1930 visit to Buenos Aires, I came across an article in the Spanish-language weekly Mundo israelita, titled “Minkowski, Goldenberg, and Our Community.” The author, Sabetay J. Djaen, was a frequent contributor to that newspaper. He was also the Chief Rabbi of Argentina’s Sephardic community.

In that article, Djaen discussed an exhibit of Minkowski’s artworks that he had visited, along with the Yiddish actor Samuel Goldenberg’s recent production of August Strindberg’s play The Father. Djaen lamented that Minkowski’s paintings went largely unsold and Goldenberg’s magisterial performance as Captain Adolf was wasted on an empty hall. “Where are our Jews?” he asked. “Where are the friends of art in this great metropolis?” Djaen concluded with a harsh assessment of the materialism, hedonism, and cultural indifference of the community that he served: “The 200,000 Jews who are scattered about our clubs and centers exist in a vacuum, amidst so many soirées [tertulias], so much tango, etc., etc.”1

Strindberg’s drama revolves around the marital discord between a freethinking but authoritarian patriarch, Captain Adolf, and his calculating wife Laura, regarding their daughter Bertha’s education. The Captain, concerned about the negative influences that his child might absorb were she to remain at home, intends to send her away to train as a schoolteacher. Laura, on the other hand, is determined to keep her daughter at home. She contends, moreover, that only the mother really knows the identity of her child’s father—insinuating thereby that Adolf might not, in fact, be Bertha’s father. If true, this would nullify his legal rights to determine the child’s future. Laura convinces the family doctor that the Captain has gone mad, which provokes the Captain into committing an act of violence. The doctor commits him to an asylum; the Captain’s childhood nurse cajoles him into a straitjacket; the Captain suffers a stroke and finally he dies.

But, to quote Sabetay Djaen, “This is not the moment to speak of Strindberg—about whom so much has been written concerning his work and talent. My sole desire here is to highlight the art of Sam Goldenberg, whom we have seen in several Yiddish theatre performances at the [Teatro] Excelsior.” Djaen’s enthusiasm bordered on the hyperbolic: “He is great, sublime; his creations are natural yet magical; they grab the viewer; he carries us along… The writer of these lines has had the occasion to see High Priests of the Temple of Thalia in this role. However, Sam Goldenberg surpasses them. He is unique—he is brilliant in this performance.”

One of the more incongruous aspects of Sabetay Djaen’s encomiums is that they emanated from the pen of a native speaker of Ladino (Judeo-Spanish). Djaen’s own plays in Ladino had been performed in Belgrade, Sarajevo, Salonika, and other cities of the Balkan Sephardi diaspora.2 In 1927, a Latin American journalist was struck by the rabbi’s “archaic Castilian,” tinged as it was with the “ancient Ladino romance.”3

Sabetay Djaen was born circa 1883, whether in Belgrade, Sarajevo, or in a different city in neighboring Bulgaria (accounts vary), and he was educated in Istanbul and Jerusalem. As a committed Zionist, Djaen embraced an expansive approach to Jewish culture and politics. He was at ease in his interactions with Sephardi and Ashkenazi religious leaders, government officials, Jewish community leaders, and Argentine Zionist leaders, as well as with ordinary people.4 His personal ties extended to Yiddish-speaking circles in Argentina and he evidently understood enough Yiddish to appreciate an evening of Goldenberg performing Strindberg at the Teatro Excelsior.

So, who was this Goldenberg fellow? What was he doing in Argentina? Why was he putting on a play by Strindberg, in Yiddish no less?

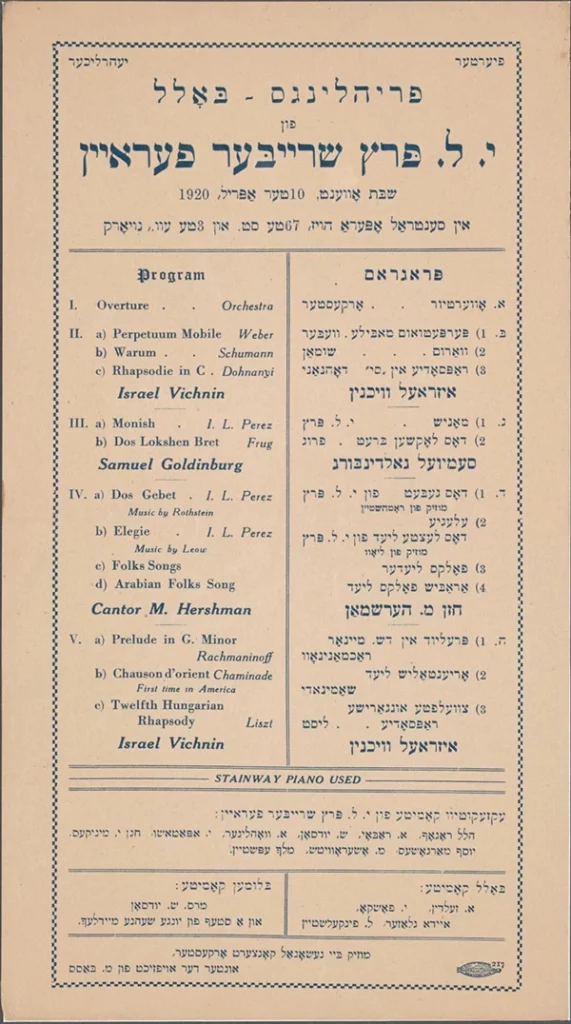

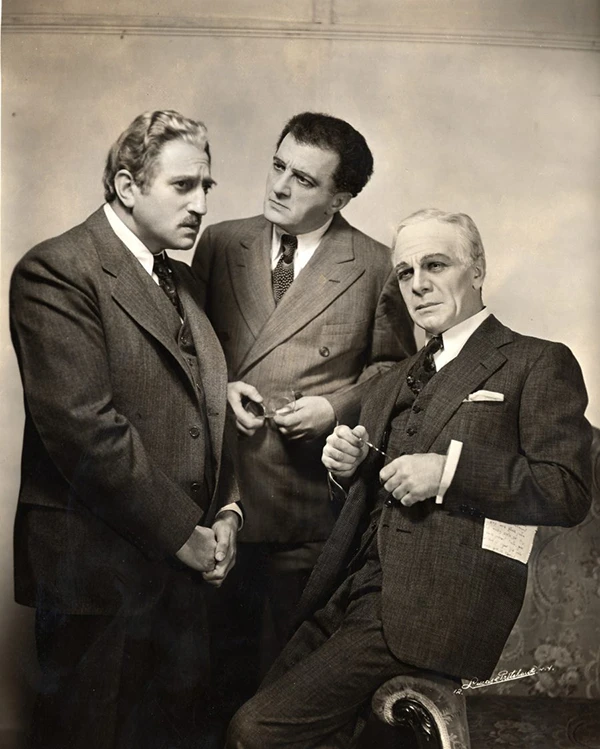

Samuel Goldenberg (the name was also spelled Goldenburg and Goldinburg) was an unusually versatile performer. Born in Brest-Litovsk in 1886, he received musical training at the Warsaw Conservatory. After he left tsarist Russia in order to avoid military conscription, he worked for a time as a piano teacher in London, and then wandered between Paris, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Argentina, before arriving in New York City in November 1916. This tall, “craggy-featured actor-singer-pianist” (film historian J. Hoberman’s description5) was often typecast as the romantic lead. Many of the plays in which he performed included musicians among the principal roles, thus enabling Goldenberg to exercise his multiple talents. As the resident star in the numerous companies with which he performed, he frequently served double-duty as the productions’ director.

The Teatro Excelsior, where Goldenberg’s performances of The Father took place, billed itself as the only full-time Yiddish theatre in Buenos Aires. It was located on Avenida Corrientes, adjacent to the Mercado de Abastos (the city’s large indoor market) in the heart of the Jewish immigrant district. The Excelsior’s season ran for eight months, from February to October, and Goldenberg was engaged there as star from June to October 1930. For several weeks he was joined by Stella Adler, also visiting from New York City.

The Excelsior’s audiences had an opportunity to see him in upwards of twenty plays—mostly melodramas, comedies, and musicals from the New York repertory, bearing such titles as In a Romanian Tavern, The Latest Fashion (a kind of Yiddish flapper comedy), Blind Jealousy, In a Web of Sin, and The White Slave. The latter two potboilers, which played to packed houses in early September 1930, were of keen topical interest to Jewish audiences in Buenos Aires. Their performances came just a few weeks before the mass arrests of over 100 members of the Sociedad Zwi Migdal, whose chief business was trafficking in international prostitution.6 These were plays that Goldenberg had performed repeatedly throughout his career.7 Toward the end of his run he also staged and starred in Zisye Goy, a brand new melodrama by the local author Samuel Glasserman (Glazerman), about a “Jewish gaucho” who wants his daughter to marry a respectable Jewish lad from the city.

Only very occasionally were productions such as these counterbalanced by plays of a more literary bent; The Father was one of those rare exceptions. Throughout his career, Goldenberg would decry the preponderance of shund in his personal repertory, blaming it on the theatre managers, the theatre unions, the tyranny of the box office, and (ultimately) the theatre-going audience. He proclaimed his disdain for the “star system” that dominated the Yiddish theatre, even though he stood as a prime exemplar of that system. At $500 a week (at least early on in his New York career), it paid the rent. Nevertheless, among the few literary plays by European authors in his repertory, Strindberg’s The Father was one of his favorites, and he performed it throughout his career.

At the Excelsior, The Father had three performances (September 19, 20, and 21) shortly before Rosh Hashanah, and was revived for one final performance about three weeks later (October 8).8 Given that his newspaper article about The Father was published in mid-October, Rabbi Djaen probably attended its fourth and final performance, which took place on a Wednesday. (Theatre managers often consigned literary plays to midweek, when turnouts and box office receipts were lower than on the weekends.)9

By contrast, attendance at the Friday night opening of The Father was high, surprisingly so in the view of the Yiddish critic Shmuel Rozhanski (Rollansky), and Goldenberg’s performance was warmly greeted by the audience.10 Following the performance, Goldenberg himself proclaimed, “I thought that the production of such a literary play—a non-Jewish one—would draw at most a minyan. It’s encouraging to have such a reception!” Rozhanski wrote a generally positive review for the daily newspaper Idishe tsaytung, though he felt that Strindberg’s emphasis on the “brutal enmity between man and woman” was played down through the production’s portrayal of the Captain as a suffering victim of his wife’s calculating caprices. “The prose and the scenes were Strindberg’s, but Strindberg’s spirit was lacking… The play was faryidisht un farheymisht”—in other words, the interpretations were watered down for a Yiddish-speaking audience that for weeks on end had been fed a steady diet of trite melodramas at the Teatro Excelsior.

How did the actors manage the pivot from melodrama to literary tragedy? In Rozhanski’s opinion, the female lead Sarah Sylvia (who played the Captain’s wife Laura) “liberated herself” from the sentimentalized characterizations to which she had inured her audiences, but “she did not play up the drama, leaving a tepid impression.” Goldenberg, by contrast, scarcely deviating from his regular stage practices, “greatly elevated himself – he provoked and he cajoled, occasionally cutting to the quick, to excellent effect in the rapid-fire dialogues.” Goldenberg had an “immense talent,” wrote Rozhanski, “to make his roles light and extraordinarily accessible” to his audiences – and that is precisely how he played Captain Adolf in The Father: naturally, subtly, “with elasticity,” and without excessive artifice.11 Though Rozhanski and Djaen ultimately parted ways about this production’s faithfulness to the playwright’s artistic intentions, they did agree about the effectiveness of Goldenberg’s technique. Rozhanski summed it up: “Goldenberg’s Captain was a handsome theatrical figure, with considerable expression in his glances and gestures. His glances were much more intense and more touching than his gently enunciated words.”

Notwithstanding Rabbi Djaen’s observations, The Father’s four performances were thus hardly an indicator of the Yiddish theatre-going audience’s indifference to works enjoying a high literary reputation. Arguably, it was Djaen’s misfortune to be present at the one midweek performance where the audience did indeed comprise “a minyan.” However, that evening’s sparse attendance provided him with the cudgel with which to beat the Jews of Argentina. It is not altogether surprising, therefore, to learn that Rabbi Djaen’s tenure there as Chief Sephardic Rabbi was of brief duration. The following year (1931), he departed for Bucharest, Romania, serving as Chief Rabbi of that country’s Sephardic community through the traumatic wartime years of the Iron Guard regime, until he escaped in March 1944. Djaen died in 1947, in Tucumán, Argentina, while on an extended visit to South America.

As for Goldenberg, following his 1930 stay in Buenos Aires, he hit the road again, with extended periods in such cities as Chicago, Los Angeles, Warsaw, and Buenos Aires once again. Like a number of other Yiddish stars, he occasionally crossed over to the English-language stage, most notably in productions of New York’s Theatre Guild and in the Biblical pageant The Eternal Road, which was directed by Max Reinhardt in 1935. He made an unsuccessful foray to Hollywood; his one and only movie, Shir ha-shirim (based on the musical by Anshel Schorr and Joseph Rumshinsky), has been “mercifully lost,” in J. Hoberman’s view. Goldenberg also performed on WEVD’s Forward Hour, in a series of radio broadcasts devoted to historical topics. The obscurity into which he has fallen since his death in 1945 may be attributed at least in part to the disappearance of the Shir ha-shirim film and the absence of recordings of his baritone singing voice.

Goldenberg’s career illustrates the dilemmas facing even the most talented performers—including ones with higher artistic aspirations—on the American Yiddish stage. A couple of years after he arrived in the United States, Goldenberg professed that he was willing to take a big pay cut in order to perform with a company that was devoted to a more artistic repertory. In the early 1920s one such troupe, Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theatre, did arise—and Goldenberg did perform there off and on. But, as he commented early on, Schwartz—ostensibly an opponent of the Yiddish theatre’s prevailing business model—was in reality his house’s star, and other stars had to look elsewhere for public exposure and their livelihoods.(Indeed, Goldenberg’s gastrol in Argentina was partially eclipsed by Schwartz’s, who was the visiting star on a rival Buenos Aires stage from June to August 1930.) Finally, Goldenberg’s musicianship, coupled with his desire to please his audiences, militated against his performing a predominantly literary diet of classical plays lacking musical interludes. In her memoirs, the actress Celia Adler (Stella’s half-sister) recalled a topical revue, The Crooked Mirror, which enjoyed a couple of performances at the Yiddish Art Theatre in the early 1920s. In a sketch by the humorist Moyshe Nadir, “one scene was about the popular Yiddish actor Samuel Goldenberg, who loved to play the piano to demonstrate his virtuosity, and in a scene where he could play the piano, he played to his heart’s content.”12 Oh, to have witnessed such a scene!

Notes

- Sabetay J. Djaen, “Minkowski, Goldenberg y nuestra colectividad,” Mundo israelita (Buenos Aires), October 18, 1930.

- Three Ladino plays by Sabetay (Shabtai Yosef) Djaen were published in Vienna in 1921–1922: Yiftaḥ (1921); Devorah (1921/1922); and La iz’ah del sol (1922).

- “Vengo en busca de mis hermanos… el gran rabino sefardí Sabetay J. Djaen nos habla de su viaje,” Crítica (Buenos Aires), April 16, 1927. With thanks to Ricardo D’Jaen (Seattle), for providing a photocopy of this article.

- Adriana M. Brodsky, Sephardi, Jewish, Argentine: Creating Community and National Identity, 1880–1960 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016).

- J. Hoberman, Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film between Two Worlds (New York: The Museum of Modern Art; Schocken Books, 1991), 207.

- Maurice Schwartz performed the more highbrow Got fun nekome (God of Vengeance) by Sholem Asch—a play that has “legs” to this day—at another theatre in Buenos Aires, where he was touring from June to August 1930.

- Goldenberg had honed his acting chops during a two-year stint in Buenos Aires (1914–1916), which is where he learned many of the roles that he would perform over and over again, for many years.

- During the High Holy Days, the Excelsior’s auditorium became a performance venue of a different sort, with the famous cantor Gershon Sirota—visiting from Warsaw—leading religious services there.

- Alef Alef [Efroym Oyerbakh (Ephraim Auerbach)], “Farvos shpielt Semuel Goldinburg shund?” in Di tsayt (Die Zeit; New York), October 28, 1921.

- “‘Der foter’, oyfgefihrt durkh Samuel Goldenburg in teater ‘Ekselsyor’,” Idishe tsaytung, September 21, 1930. The review is unsigned but is almost certainly by the newspaper’s cultural critic, Shmuel Rozhanski.

- Goldenberg more than once proclaimed himself an adherent of the methods developed by Konstantin Stanislavski at the Moscow Art Theatre.

- Celia Adler (assisted by Ya’akov Tikman), Tsili Adler dertseylt (The Celia Adler Story) (New York: Celia Adler Foundation, 1959), vol. 2, 578. See also David S. Lifson, The Yiddish Theatre in America (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1965), 351.

Article Author(s)