Franz Kafka’s Vagabond Stars

On February 18 1912, a Prague businessman and little-known German-language writer named Franz Kafka introduced an evening of Yiddish literary recitations in the city’s Jewish Town Hall.

… once Yiddish has taken hold of you and moved you—and Yiddish is everything, the words, the Chasidic melody, and the essential character of this Eastern European Jewish actor himself—you will have forgotten your former reserve. Then you will come to feel the true unity of Yiddish, and so strongly that it will frighten you, yet it will no longer be fear of Yiddish but of yourselves.*

Franz Kafka

Kafka had become enamored of Yiddish theatre in May 1910; by the time a company of Yiddish actors from Lemberg (Lviv) came to Prague a year later, they would feature prominently in Kafka’s life, dreams, and diaries. This article looks at the lives of these Yiddish actors, who sparked a fevered enthusiasm for Jewish theatre in one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, and left significant traces on short stories like The Judgment and The Metamorphosis, and on the novels The Trial and The Castle.1

Between September 1911 and January 1912, the small Yiddish theatre company that entranced Kafka performed at the Café Savoy (now the Katr Restaurant on Vězeňská Street) in Prague, not far from the Old Town Square. In a cramped room of the restaurant, among the dining tables, the troupe performed plays by Avrom Goldfaden, Jacob Gordin, Joseph Lateiner, Avrom Mikhl Sharkansky, Sigmund Feinman, and Moyshe Richter, preceded by a variety of Yiddish songs, couplets, and jokes. The audience was noisy and unrefined, and Kafka found the actors “full of the melody” of the Yiddish songs that caught “hold of every person” in the audience(Diaries, October 6, 1911).The Lemberg Company included Süsskind Klug and his wife Flora (Goldberg) Klug, Emanuel and Mania Tschissik, Jizchak Löwy, Mano Pipes, R. Pipes, and Sami Urich. They presented themselves as the “German-Jewish Company from Lemberg,” even though not all the actors were from Lemberg, or “German.” Lemberg had prestige, since the first permanent Yiddish theatre in Europe was founded there. Great actors like Bertha Kalich and many others who came to fame in a variety of central European theatres came from this Galician city. Yiddish actors from Lemberg also enjoyed fame overseas, because their melodies were recorded using the latest in musical technology, the 78 rpm record, which reached the height of its popularity in the 1920s.

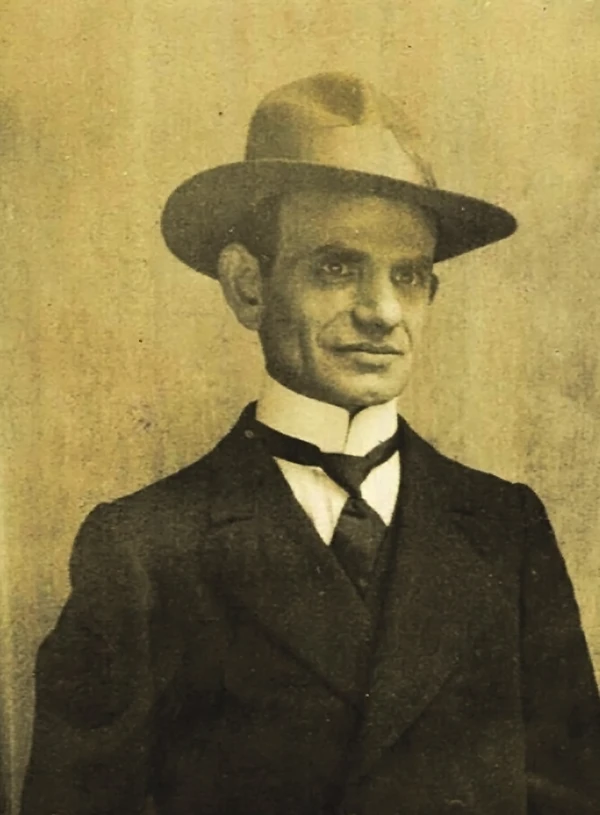

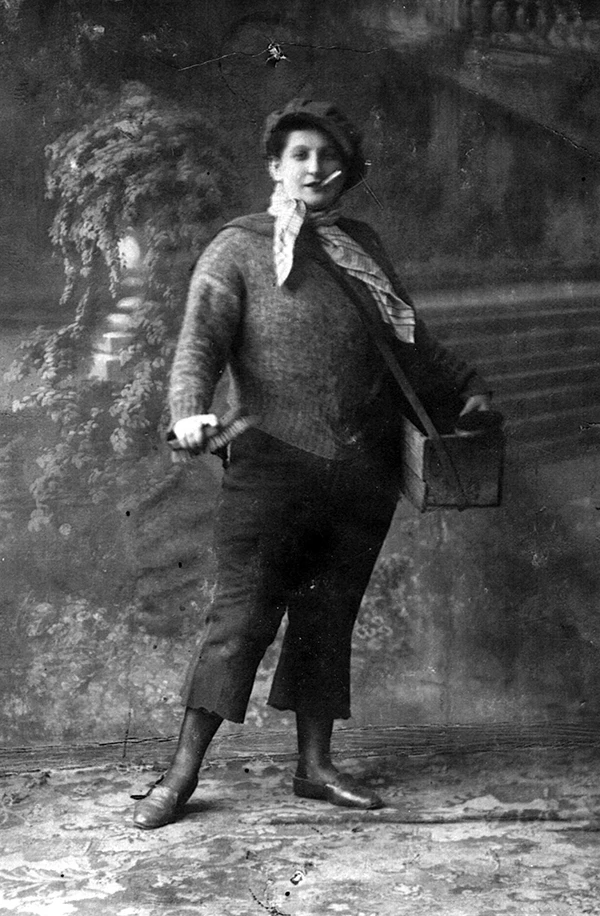

Süsskind Klug and Flora Goldberg Klug (Florence Klug)

Süsskind Klug was born in Brody, Poland (now Ukraine) in 1874. In Poland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he probably acted in a company formed by a Broder zinger, the generic name for the popular Yiddish singers who laid the foundations of modern Yiddish theatre many years before Goldfaden. Flora Goldberg was born in 1886 in Sierpc, a Polish city under Russian rule. She and Süsskind met in London and married in 1902 at the Fieldgate Street Synagogue when Flora was only sixteen, a fact that Kafka noted in his diaries. The Klugs spent time in Vienna, Berlin, Leipzig, Carlsbad, and Budapest, their home when not on tour. Flora was a singer and character actor. Of her performance as a young Hasid, Kafka noted:

“Mrs. Klug, ‘male impersonator.’ In a caftan, short black trousers, white stockings, from the black shirt a thin white woolen waistcoat emerges that is held in front at the throat by a knot and then flares into a wide, loose, long, spreading collar. On her head, confining her woman’s hair but necessary anyhow and worn by her husband as well, a dark, brimless skullcap, over it a large, soft black hat with a turned-up brim (Diaries, October 5, 1911).

Kafka thought that Flora Klug’s Hasidic characters had a satirical edge, as portraits of a people “set apart” from the world outside, but deeply immersed in Jewish life and community, who “see clearly to the core the relationship of all the members of the community.” Like Sholem Aleichem’s luftmentshn, they “haven’t the slightest specific gravity but must bounce right back up in the air”(Diaries, October 5, 1911). Newspaper reviews noted that Flora Klug had an explosive vitality that captivated audiences. Her melodies and Yiddish phrases made Kafka feel, for the first time, part of a larger Jewish family, “…because she is a Jew, [she] draws us listeners to her because we are Jews, without any longing for or curiosity about Christians” (Diaries, October 5, 1911).

During World War I, the Klugs returned to Prague, and from September 1916 to April 1917, they performed at the Hotel Schwan, a short walk from Kafka’s office. In Prague they formed a company called the “Jewish-Polish Orfeum,” with Süsskind as manager, and Flora in leading female roles. In 1920, Süsskind Klug died in Budapest, and the following year Flora emigrated with their children to New York. She settled in the Bronx and acted there with many companies under the name Florence Klug. In 1925, she was featured in Betty Kenig’s company’s production of Goldfaden’s Akeydes Yitskhok (The Sacrifice of Isaac), and by 1931, Florence Klug was with Charles Goldstein’s “European Yiddish Art Troupe.” In 1933, she performed as a singer at the Thomashefsky International Music Hall on Freeman Street in the Bronx. In the early fifties, Florence moved to California with her third husband, Isadore Vernick, a Yiddish actor and director from Odessa. Vernick lived in Hollywood and counted Paul Muni and Bela Lugosi among his friends. Florence died in May 1954 after a long life of incredible adventure; she overcame difficulties of all kinds, and inspired Kafka to say, “Listening to her always lively singing does nothing less than prove the solidity of the world, which is what I need, after all” (Diaries, 19 December 1911). On her grave in the small cemetery of Commerce, California, an inscription reads: “A trouper to the End.”

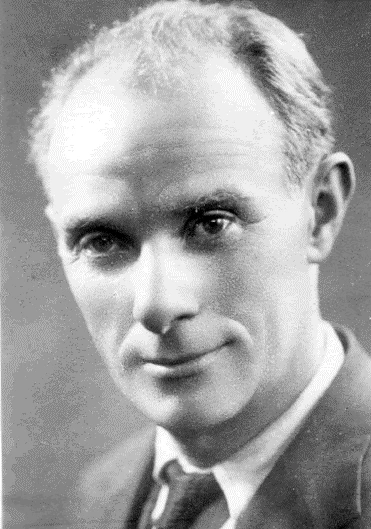

Emanuel and Mania Tschissik (Emanuel Cyżyk and Millie or Amalie Chissick)

On November 6, 1911 Kafka sat beside Mania Tschissik at the Café Savoy. He had seen her perform in Goldfaden’s Shulamis and Bar Kokhba, but in the café he tried not to glance Tschissik’s way, “For that would have meant that I loved her” (Diaries, November 7, 1911). Kafka was enraptured with her beauty and her voice, but his passion for Mrs. Tschissik had to be channeled into the bouquet of roses that he sent as a sign of devotion. In his diaries, Mania Tschissik becomes an elusive and surreal figure, “she reminded me vaguely of hybrid beings like mermaids, sirens, centaurs”(Diaries, December 19, 1911).

Mania Tschissik (née Ferstenfeld) was born in Częstochowa, Poland around 1881. Her father owned a pub frequented by touring Yiddish actors, and it was there that she met Emanuel Tschissik, an actor, singer, playwright, and Yiddish songwriter. Emanuel was born in Warsaw in 1867 and his father, Binem Badchen, had joined one of the early Yiddish theatre companies. Mania and Emanuel eloped and moved to London. When war broke out in 1914, Emanuel was in Prague, where he performed with the Klugs. In the 1920s, he went to Paris where he earned a living selling his song lyrics. He died in a nursing home in Paris in 1947. Mania returned to London in 1914 and continued to perform in Yiddish as Millie Chissick. For many years the public at the Pavilion Theatre and the Grand Palais applauded her as a perfect interpreter of Yiddish classics. She died at the age of 95 in September 1976.

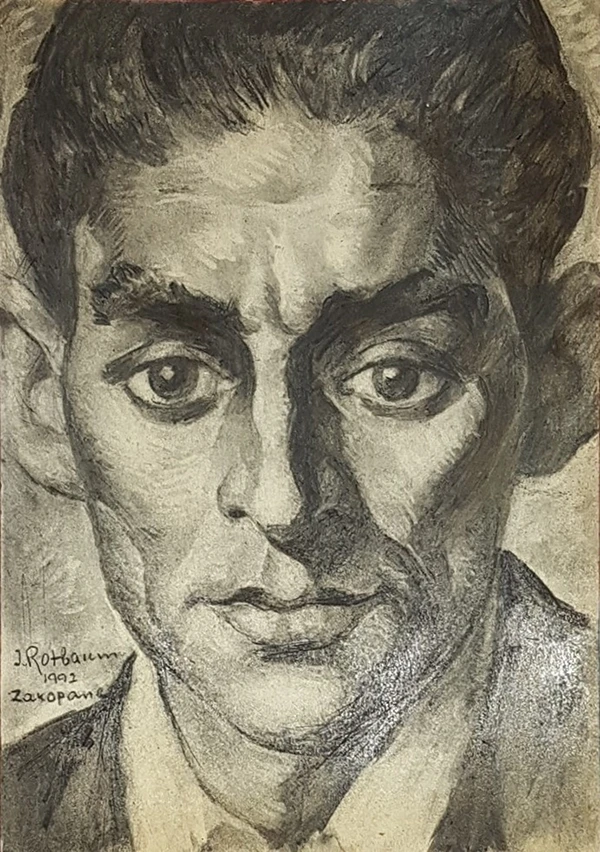

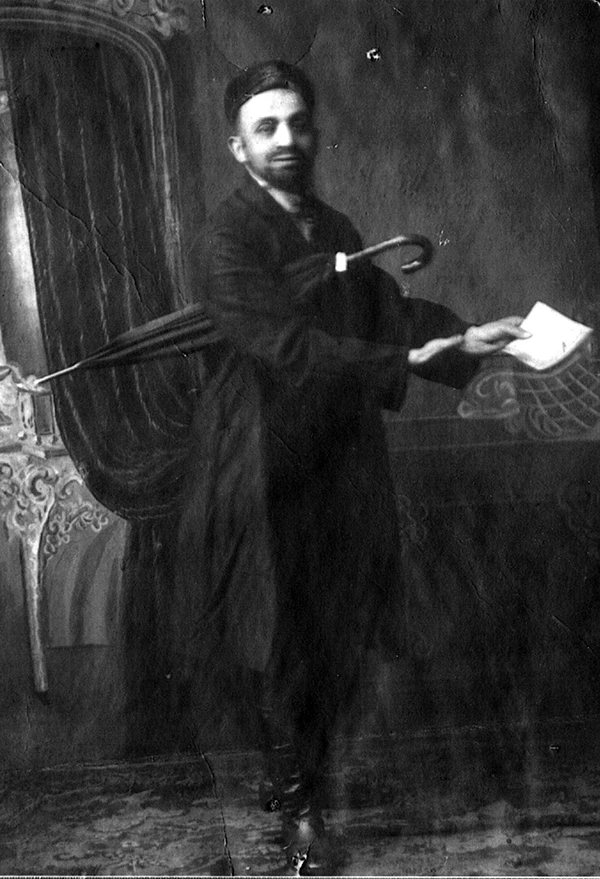

Jizchak Löwy (Jacques Levi)

The performance that Kafka introduced at the Jewish Town Hall was by Isaac Meir Levi, aka Jizchak Löwy/Jacques Levi/Jack Lewi, an actor with whom the writer had developed a close friendship.2 Löwy was the most complex and tormented personality of the Lemberg Company. His extraordinary expressive force struck Kafka:

He steps forward only a little, opens his eyes wide, plucks at his straight black coat with his absent-minded left hand and holds the right out to us, open and large. And we are supposed, even if we are not gripped, to acknowledge that he is gripped and to explain to him how the misfortune, which has been described, was possible (Diaries, January 7, 1912).

The actor’s “unquenchable” and “infectious fire” shook Kafka, who saw an alter-ego in Löwy, an artist who was often stymied and isolated by his anxieties.3 For Kafka, Löwy became an “indispensable friend,” but one whose visits infuriated Kafka’s father, who reminded his son that “Whoever lies down with dogs gets up with bugs” (Diaries, November 3, 1911). Kafka may have had these words in mind one year later in 1912, when he began writing The Metamorphosis.

Löwy was born Isaac Meir Levi in Warsaw in 1887 to a wealthy Hasidic family. He attended kheyder and, for a time, the Ostrog yeshiva in Volhynia.4 A passion for theatre led him to Paris, where in 1906 he made his debut with the nascent Bundist amateur company Fraye yidishe arbeter bine (Free Jewish Worker’s Theatre), performing in Chekhov’s one-act comedy Medved’ (The Bear). Löwy also spent time acting with Mania Trilling’s company and her husband Herman Berman. In the years that followed, Löwy performed in Berlin, Vienna, Carlsbad, and Marienbad. In Germany, Löwy learned Felix Hollaender’s and Max Reinhardt’s theatrical techniques, and in 1913 founded his own company, which soon went bankrupt. To help buttress Löwy’s fledgling company, Kafka organized a second recital of Yiddish literary texts on June 2, 1913. During World War I, Löwy lived in Budapest, and was successful on the Yiddish variety stage, performing under the name Jacques Levi. In 1919, he returned to Warsaw, and between 1921 and 1925 Löwy often toured with Jonas Turkow. In 1924, Löwy founded a Hebrew-language theatre studio, ”Habima,” modeled on the Moscow company of the same name. While in Poland, Löwy made a name for himself as a performer of monologues. Traveling tirelessly between Warsaw and the Polish provinces, he brought Yiddish and Hebrew literature to the masses, as well as performing Shakespeare, Molière, Schiller, Gogol, Dickens, Poe, Chekhov, and Stefan Zweig. His interpretation of “Ver bin ikh?” (Who am I?), based on I. L. Peretz’s story “Der meshugener batlen” (The Mad Talmudist), was unforgettable.

In the 1930s, Löwy wrote for the Warsaw-based Yiddish newspaper Unzer ekspres and during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, he fondly remembered Prague and his friend Franz Kafka, who had died of tuberculosis fifteen years earlier.5 Isaac Bashevis Singer knew Löwy in Warsaw and wrote a poignant portrait of him in the short story “A Friend of Kafka.”

During the war, Löwy was interned in the Warsaw Ghetto. On December 6, 1940, he returned to acting at the ghetto’s Eldorado Theatre in the comedy In reydl (In a circle). He appeared in public for the last time on July 18, 1942, interpreting songs from the Book of Job and other Biblical texts. He and his parents were deported to Treblinka in August, 1942.

Zalmen and Basia (Sauber) Liebgold

Zalmen and Basia Liebgold were character actors with the Lemberg company; both were excellent singers, too. Zalmen Liebgold was born in Kraków in 1875; Basia Sauber in Przemyśl around 1890. They were married in 1908 and lived for many years in Austria, Romania, Slovakia, and Bohemia. In the 1930s, the Liebgolds lived in Warsaw, where Zalmen managed a theatre, in which Basia starred with their son, Leon, who would later enjoy success in films like Der dybbuk and Yidl mitn fidl. Basia and Zalmen Liebgold were interned in the Tarnow ghetto and murdered in Treblinka in 1942. Leon Liebgold was in the U.S. when the war broke out. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, he was president of the Hebrew Actors’ Union and of the Yiddish Theatrical Alliance. He died in 1993 in New Hope, PA. Among his papers are these photographs of his parents.

These are rare and valuable images of the Yiddish theatre that Kafka loved. The small theatres – cabarets, opera, and operetta companies – that traveled throughout central Europe may have been poor in material resources, but they were rich in talent. The essence of this theatre was summed up by Jizchak Löwy with these words: “… and indeed everything was together here: drama, tragedy, song, comedy, dance, all together – life!”6

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank the Chissick, Gibson, Klug, Liebgold, and Ronin families for their friendship and for the photographic materials that they have made available, and Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel. I would also like to thank Bernard Mendelovitch (z”l), who provided tremendous insight into Millie Chissick and her family.

* All diary entries are from Franz Kafka, Diaries 1910-1923, edited by Max Brod. Translation by Joseph Kresh (New York: Schocken, 1948).

** Translated from Italian by Nick Underwood, edited by Barbara Henry.

Footnotes

- Kafka’s diaries record his seeing the following plays: Shulamis and Bar Kokhba (Goldfaden); Der vilder mentsh (Gordin); Dovids fidele, Di seyder nakht, and Blimele, di perle fun varshe (Lateiner); Der meshumed (Khofni un Pinkhes); Kol-nidre (Sharkansky) and Der vitse-kenig (Feinman). On Kafka and the Yiddish theatre see Evelyn Torton Beck, Kafka and the Yiddish Theater: Its Impact on His Work (Madison WI, 1971); Iris Bruce, Kafka and Cultural Zionism (Madison, WI, 2007), 34-56.

- On Emanuel and Mania Tschissick see: Leksikon fun yidishn teater, vol. 2 (New York, 1931), 899-901; Samuel Jacob Harendorf, Teater Karavanen (London 1955), 52- 54.

- “Introductory Talk on the Yiddish Language,” in Franz Kafka, Dearest Father: Stories and Other Writings, trans. Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins (New York, 1954), 381-386. Löwy performed the poetry of Rosenfeld, Frug, Frischmann, Reisen, Nomberg, Nisn Dranow, Sholem Aleichem, and Hasidic songs.

- Letters to Felice Bauer, 1 June and 10 June 1913. On Löwy see Leksikon fun yidishn teater, vol. 5 (Mexico City, 1967), 4153-4158; Jonas Turkow, Farloshene shtern, vol. 1 (Buenos Aires, 1953), 92-99.

- “Khurbn prog” (The Destruction of Prague), 7. Unzer ekspres, March 24, 1939: 8.

- From an article by Löwy on his introduction to the Jewish theatre. Kafka translated the first part of this paper for Martin Buber’s journal Der Jude. The article was never published.

Article Author(s)

Guido Massino

Born in Turin, Italy, Guido Massino is Assistant Professor of German Literature at the University of Eastern Piedmont, Vercelli. His research focuses on Franz Kafka’s encounters with Yiddish theater, and, in 2007, he published Kafka, Löwy und das Jiddische Theater.