Curtain Falls on the Sunshine Theatre

A FEW WEEKS ago, a journalist from the New York Times informed me that the Sunshine Cinema at 143 East Houston Street would go dark for good. Worse yet: the building’s new owners plan to demolish the historic movie theater, which reopened in 2001 after a $12 million renovation by the Landmark Theatre Corp. The news came as a shock. On every visit to New York City, I would enjoy a movie at the renovated Sunshine. I know its history by heart, as I wrote part of my PhD dissertation on the place. For over a century, it functioned as a neighborhood cornerstone: first as a church for Dutch settlers and German immigrants, then as a Yiddish music hall, and finally as a movie theatre, where Jewish and Italian newcomers watched the latest talking pictures.

The story of the Sunshine Theatre begins with an ambitious young Hungarian-Jewish immigrant, Charles Steiner (1883-1946). In 1908, he had gone into the film exhibition business by turning his father’s livery stable on Essex Street into a five-cent movie theatre. “Charlie” was good at it, and a few months later he had saved enough money to open another picture show in a former kosher sausage factory on Monroe Street. But the location was not ideal, so he was looking for a better opportunity. Steiner discovered that an old Protestant church on East Houston Street was for sale and suggested to a friend that if they could raise the money to buy the building, they “could take a stab” at the booming Yiddish music hall business. This friend happened to be Abraham Minsky (1882-1949), the oldest of the legendary Minsky burlesque brothers. Now, Abe Minsky did not have a penny to his name, as he loved gambling and womanizing a little too much. But his father was a rich man. Louis Minsky had made a fortune in dry goods and real estate. Pa Minsky must have immediately recognized that the old church was an excellent real estate investment. There were few lots of this size on the market and if the new theatre was a success, he could resell it at a profit. At the same time, as a devout Jew and prominent member of the Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun, he was not particularly thrilled by the idea of setting up his son in the entertainment business. Perhaps he also felt a little uncomfortable about turning a church into a theatre. Yet in the end, Louis Minsky bought the property for the nice sum of $96,000 (the equivalent of $2,600,000 today). The legal documents reveal that he was not very picky about his partners: financial backing came from the notorious “kosher chicken czar” and Tammany District leader Martin Engel, who owned several brothels and concert saloons in downtown Manhattan.

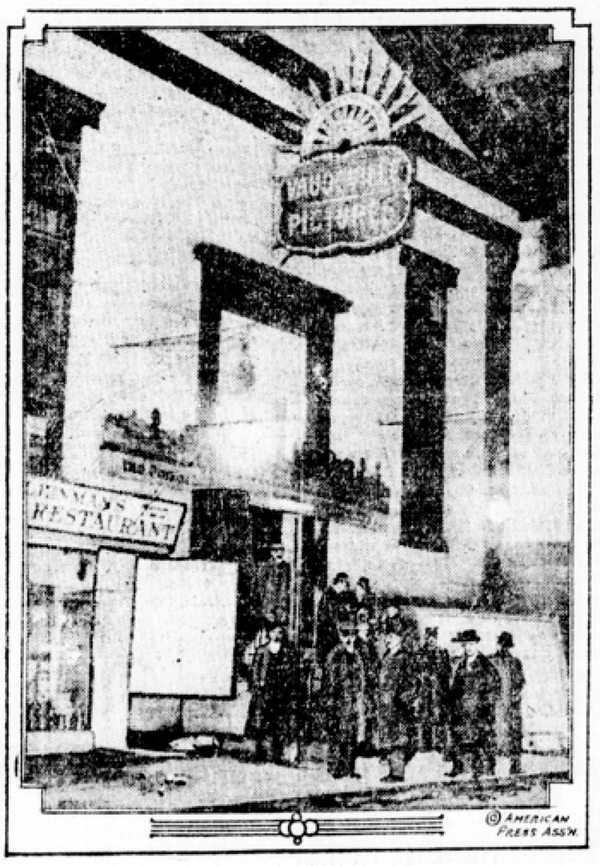

With a couple of minor alterations, the former church was converted into a vaudeville and moving picture theatre. The walls were painted, the pulpit gave way to a small stage, and the organ loft became the projection booth. Steiner and Minsky kept the old wooden church pews, which could easily seat up to 450 people. Over the next few years, the racks that once held hymnals would be frequently used for storing the bagels, salamis, knishes, and other snacks that audiences brought with them to eat during the show.

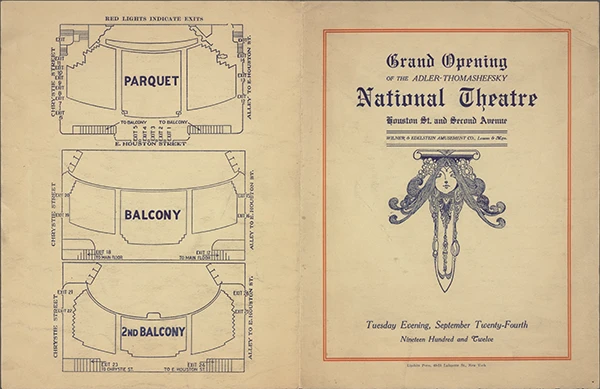

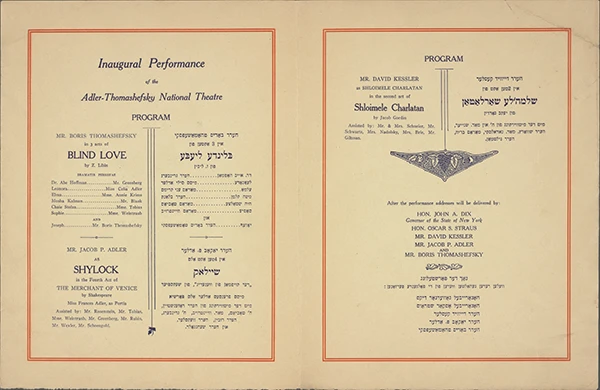

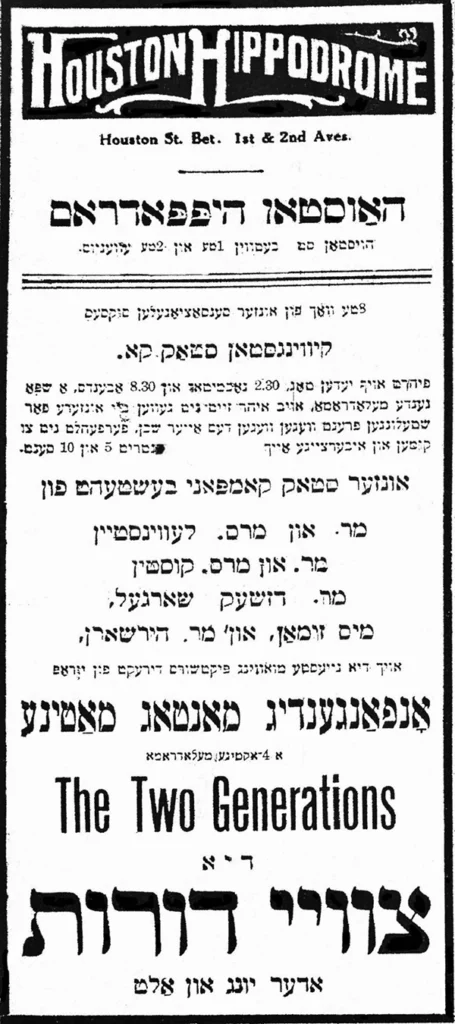

On December 3, 1909, the opening of their “Houston Hippodrome” was announced in the Yiddish press. For five cents in the afternoon and ten cents at night, patrons were promised the best moving pictures, which alternated with vaudeville acts in Yiddish and English. The new music hall was an instant success. In a way, its opening marked the beginning of the new Yiddish theatre district on Second Avenue. Two years later, Louis Minsky would, with Max D. Steuer, develop the million-dollar National Theatre at 111 East Houston Street, only two blocks west of the Houston Hippodrome. David Kessler had already left the Bowery for Second Avenue in 1911. Now Boris Thomashefsky and Jacob P. Adler were following him. Noteworthy: Minsky’s business partner in this property development was, again, a man whose reputation on the East Side was pretty bad. Steuer was the trial lawyer who had successfully defended the owners of the Triangle Waist Company from manslaughter charges after a factory fire killed 146 garment workers, many of them young Jewish women.

In retrospect, we know that Charlie Steiner and Abe Minsky had chosen the perfect moment to launch a “vaud-pic” theatre. An explosive demand for Yiddish entertainment at popular prices created a new tier between the five-cent moving picture shows and established Yiddish vaudeville theatres like the People’s Music Hall and Agid’s Clinton Vaudeville House, which charged up to 35 cents for their best evening seats, and a minimum of a dime for matinee and gallery seats. Steiner and Minsky could keep their ticket prices much lower because they programmed more movies than the existing Yiddish music halls, and hired less famous variety actors, as well as amateur talent. Also, like the nickel shows, the Houston Hippodrome remained open from 11 am until 12 pm, instead of giving only two shows per day – matinee and evening.

Did you ever pass an afternoon or evening at the

Houston Hippodrome?

Not yet? Then don’t wait,

come when you want and stay as long as you want!

We have the best vaudeville program, as well as the finest and newest moving pictures.

All this for five and ten cents admission

If you appreciate good actors, read the following names and admire our staff

Gentlemen: Mr. Kuperschmidt, Gilrod, Tuchband, Wolf, Siegel

Ladies: Miss Tuchband, Steinberg, Erven, Greenbaum and Cohn

Tell all your friends to meet you at the Houston Hippodrome,

141-143 E. Houston St.1

Initially, a show at the Houston Hippodrome contained a mix of short movies, comic sketches, dramatic scenes, one-act plays, songs and dances, perhaps with an additional animal act, juggler or acrobat. In the fall of 1910, Steiner and Minsky decided to add three-act melodramas to the bill – initially only during day-time, but later also on weekday nights. By early 1911, Houston Hippodrome offered two (!) new plays per week. Each Monday and Thursday a new piece premiered. A year later, they even began to offer four-act plays. By then, more and more nickel-and-dime theatres were offering Yiddish vaudeville at popular prices, so they clearly tried to stay ahead of the competition. The plays at the Houston Hippodrome were performed by traveling troupes consisting of six to eight actors, who were supported by a handful of young vaudevillians. These youngsters were engaged for the entire season and formed the in-house company. If a larger cast was needed, other staff members stepped in, too. Thus, we know from the publicity in the press that Steiner appeared alongside Mrs. Jeanette Atlas in Dos vayb (The Wife), while the theatre’s special policeman – a young Italian immigrant – played “the Moor” in Wallerstein’s Di kidnepers. Most stock companies stayed at the Houston Hippodrome for several weeks until they had performed their entire repertoire. We know little about these plays except their titles, which either touched on episodes of Jewish history, or dealt with the challenges of Jewish immigrant life in America.

“We offer a program that no other vaudeville house can afford,” Steiner and Minsky boasted in the Forward in January 1912. Perhaps, but were they making money? Not enough, apparently, because they were looking for a bigger theatre. For a second time, they turned to Louis Minsky for help. In the summer of 1912, the National Theater was almost completed. It was a so-called “piggyback” twin theatre with a 1,900 seat auditorium on the ground floor for legitimate performances. Minsky and Steuer had leased the main theatre to the Thomashefsky-Edelstein-Adler company, but were still looking for a lessee for the rooftop theatre, which was designed for moving pictures and vaudeville. Having outgrown the Houston Hippodrome, it was to this lavish 1000-seat “Winter Garden” with its gold and rose interior that Steiner and Minsky moved their show in late 1912. At the same time, they downgraded the Houston Hippodrome to a run-of-the-mill piktshur plats . This was the end of its history as a Yiddish theatrical venue.

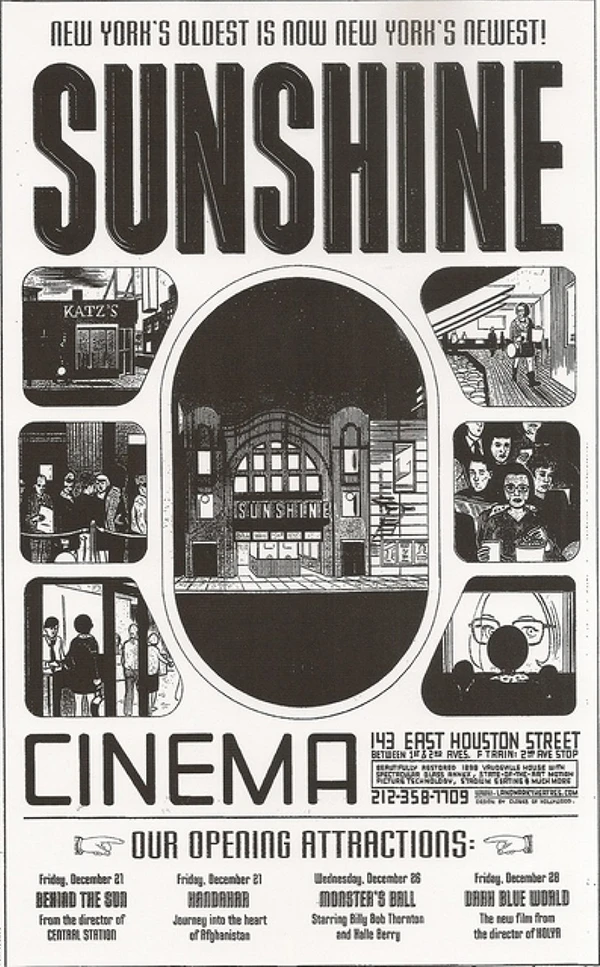

In February 1917, Steiner applied for a permit to demolish the old church building to make way to a brand-new 600-seat movie theatre, which he named the Sunshine Theatre (probably after the radiant sun in the sign above the entrance to the Houston Hippodrome). Rumors circulated in the Yiddish press that the new house would be offering Yiddish vaudeville again, perhaps even legitimate drama. It did not. The Sunshine Theatre, which opened on July 1, 1917, remained a movie theatre until the late 1940s. After that, the building served as a warehouse until 2001, when the façade was restored to its old glory and the former one-screen cinema turned into an art-house multiplex.

Real estate interests have shaped the history of Manhattan’s Lower East Side since long before gentrification started and the neighborhood began becoming fashionable. In 1909, there must have been quite a few people who were shocked to learn that Louis Minsky had bought the old Dutch Protestant church to turn it into a music hall. In 1917, others probably protested when the early-nineteenth-century building was torn down for the Sunshine Theatre. A century later, I find it difficult to understand why the cinema’s façade was not given landmark status. Demolition of the building will begin in March. I feel sad that yet another landmark of Yiddish entertainment history will have gone when I am in New York City next time. But I will still head to the Lower East Side.

Not for a movie, but for a knish. Yonah Shimmel opened his bakery at East Houston Street to profit from the crowds of vaudeville fans who went to the Houston Hippodrome for a show at popular prices. “Original since 1910,” as the sign tell us. Let’s hope it will not become an artisanal knish boutique.

Notes

- Advertisement Houston Hippodrome, Forward, April 28, 1912 (translation).

Article Author(s)