12.02.2019

“Thoughts from a Writing Challenge” by Lisa Low

Thoughts from a Writing Challenge

by Lisa Low

This January, I decided to write a poem a day for a month (à la NaPoWriMo) with a couple of friends. I thought of this as exercise—something I didn’t want to do but knew would be good for me. And like exercise, I wanted instant gratification and endorphins. Instead, I experienced daily writing as another way to approach myself, both the good and bad. Some thoughts from the month:

- Most days are unspectacular, but on the worst days, nothing is in my fingers. Or in my brain. I don’t like anything I’ve written, so I repeatedly type and backspace the way I tell my students not to do during in-class writing activities. I click through old poems nostalgically as if to harness the magic of a moment when something sprang forth out of nothing. I feel like I’ll never write something good again. It’s as if negative self-talk itself will produce the poem. On other days, a poem appears in my mind like a gift. Some lines come to me when I don’t expect it (which, in the moment, I see as magical rather than the result of practice). I sit down in Nordstrom Rack and type on my phone instead of finding new sneakers like I’d been planning to. By the time I get out, it’s dark and I’m late for dinner. In these moments, I feel most like a writer. But isn’t being a writer both of these extremes, and the more boring in-between?

- A lot of content is needed, so whatever is around me goes in a poem. I look outside my apartment window and see trees, and yes, birds. I understand more deeply why trees and birds are such favorite topics. My husband, a teacher, comes home to tell me a student asked what was wrong with his eyes. Wolf’s eyes, the second grader had said. This also goes in a poem, but I think the story of the student is better. For a few years, I’d written about what blue eyes meant to me, the desire for blue eyes, the way they pierced me as a child not used to them, and this student had described them in the shortest phrase. This, too, is a gift.

- I worry the most when I wake up in the middle of the night, and, to avoid anxiety—about the class I teach, what I said or didn’t say to someone I wanted to impress, that I worry about impressing at all—I think of poems and start writing in my head. My brain gets busy. This is the opposite of counting sheep or deep breaths. On one hand, the poem is a repository for anxious thoughts, and on the other, a diversion from them.

- My therapist asks if I’ve ever wanted to speak up but felt I couldn’t—not that I chose not to for my own reasons. My answer is a hard yes. She says it’s good that I have an outlet in writing. I haven’t thought of poetry as an outlet for years and linger over the phrasing. Later, I realize it’s because I’ve associated outlets with the outpouring of emotion—something that must be let out, that must leave the body in whatever way possible—and therefore a contradiction to craft. The careful making of something, the work of a poet. But the more I think about it, the more I don’t think outlet and craft have to conflict. The poem is, in one sense, how I retroactively speak up for the times I couldn’t, like at the oral surgeon’s office experiencing microaggressions. It’s the Yelp review I’d always planned to write.

When the month is over, I’m spent. I celebrate with boba from the newly-opened Kung Fu Tea a mile away. I haven’t taken stock of the revision ahead of me yet, the inevitable cutting and throwing away—that I can’t just throw my poems up into the air and watch them fall into place, a manuscript. Right now, the sugar and treating myself are enough like endorphins.

*

Lisa Low was born and raised in Maryland. Her poems have appeared in Vinyl, The Journal, Entropy, The Collagist, and elsewhere. A graduate of Indiana University’s MFA program, she is a PhD candidate and Yates Fellow at the University of Cincinnati.

*Low’s poems appear in Issue 42.1 of Cream City Review.

10.21.2019

“Self-Portraits” by Emily Townsend

Self-Portraits

by Emily Townsend

My senior year of undergrad, I took a nonfiction workshop twice. I was still getting adjusted to the genre, spilling out my secrets for classmates who barely knew me. I was also exploring experimental forms in essays: Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams, Kristen Radtke’s Imagine Wanting Only This, Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts. In both semesters, we covered Jenny Boully’s The Body. I remember one student (now a great friend and editor) brilliantly attempted the form in a different way, and I admired both essays so much that I wanted to try it myself.

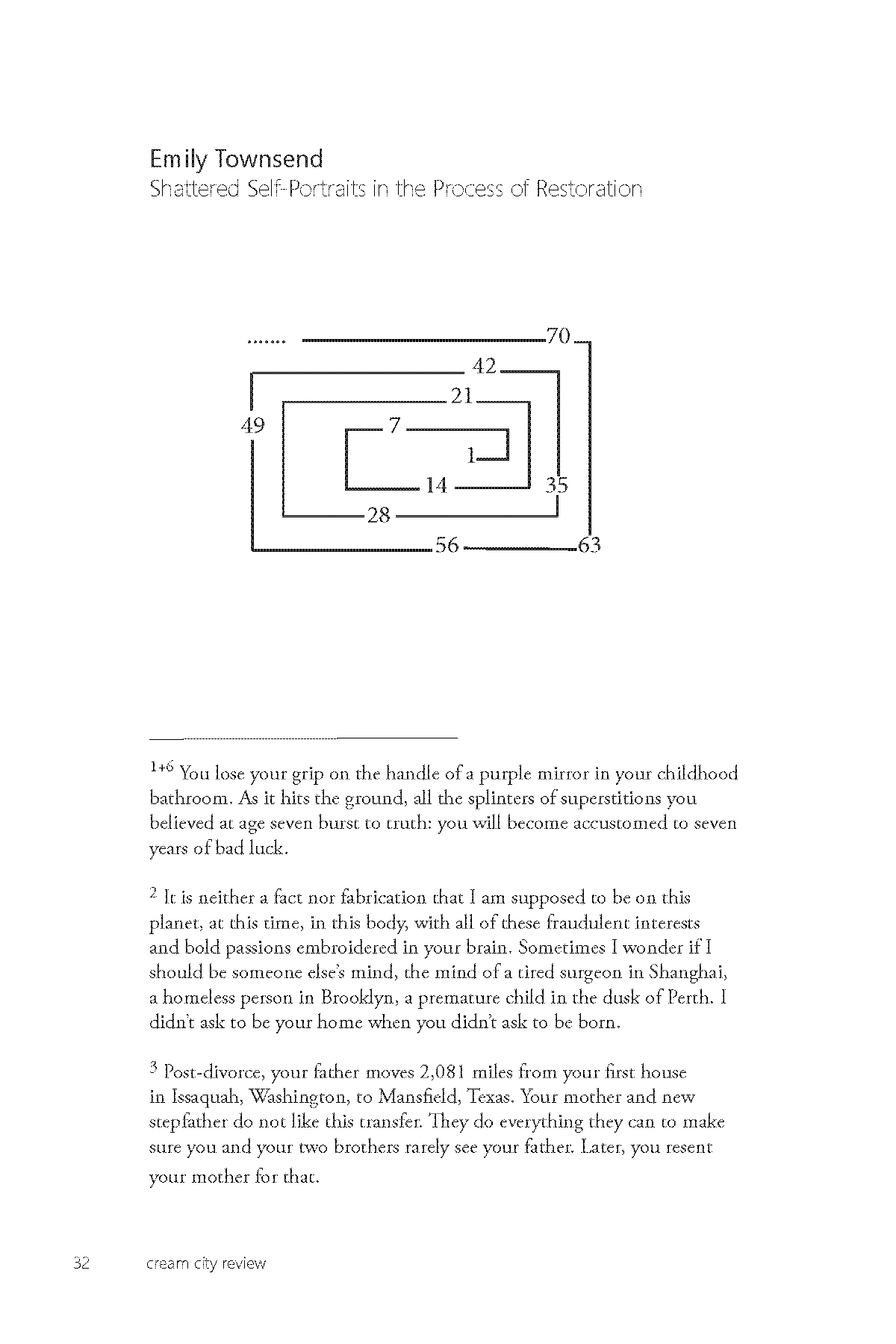

“Shattered Self-Portraits in the Process of Restoration” borrows Boully’s form of total footnotes, and my adjustments are the equations in every footnote that is a multiple of 7. Because I broke a mirror twice in fourteen years, the second at the tail-end of the first’s seven years of bad luck, it seemed that the number seven was cursed. It conveniently lifted when I turned 21. Hence the maze at the beginning of the essay: each multiple of seven is like a path inside a labyrinth that I cannot get out. One multiple will lead to a different multiple that isn’t in a correct sequence, enacting a step forward or a step backward. The last footnote’s equation is 70-69, which leads the reader back to footnote one. Even you can’t get out of this chaos.

This essay opens up my first collection, originally set to be a sort of unconventional table of contents like Dave Eggers’ prologue for A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, but then I read The Body and made each footnote a foreshadowing to the rest of the book. The blank text is essentially the entire book yet it is expatriated, as I felt while growing up away from my hometown during formative years. What bookends this essay is a 40-page rebuttal: written a year later, I finally understood my pessimism was because I willingly put myself through pain, not because of a delusion with broken mirrors. I assigned blame to an object rather than to myself because I didn’t want to properly deal with it.

Sometimes I believed my body and my brain were two entirely separate entities. I constantly struggled with figuring out where I belonged during those bad-lucked years: I was displaced from my hometown due to my parents’ divorce, I was purposely making everything harder for myself as punishment. So I took this superstition of broken mirrors and blamed my unhappiness on the accidents of dropping cheap glass onto my bathroom floor. My brain falsely assured me of a lot of things—“after high school, you’ll move back home;” “don’t worry, people actually like you”—and made me imagine a distinct person I wanted to have been real, but it was a figment of my imagination so desperate to have someone fill in that space. The ontology of my brain on its own seemed to be completely detached from my body.

The most interesting thing about this piece, to me, is how I realized I was wrong and selfish. Rarely do essays make me change my mind on myself, but I had gone through such a colossal shift of feeling lonely to feeling loved back to feeling lonely and then back to feeling loved that the distance I went through both physically and emotionally forced me to see I took so much for granted. A month after I finished writing this I moved to Eugene, Oregon, to see if my love for the Pacific Northwest was still real after a hiatus of not living there for sixteen years. It turned out to be extremely lonely and solipsistic. When I returned to Texas for grad school, I realized my friends and the community were what made me happy and alive. My first two years of college were rough, but that senior year was actually beautiful and involved and I felt like I finally had a place to fit in. I’m a bit terrified to leave in a couple months.

I’m eternally grateful Cream City Review nominated this essay for a Pushcart; it’s a great way to feel validated for a life story that gave me so much pain yet I wanted to share it with anyone willing to read. When I drive between my mother’s house and wherever I’m living while in school, I often think that I wouldn’t have such a story to tell if I didn’t go through what happened, if I stayed in one place after all, if I chose to be optimistic and bright instead. My material would either be a lot different or nonexistent. I enjoy writing dark stuff to help me confront my issues and reassign whatever blame I pin on something else back onto me. It humanizes me, forces my brain and body to rejoin, and make me see the world a little more clearly.

*

Emily Townsend is a graduate student in English at Stephen F. Austin State University. Her works have appeared in Superstition Review, Thoughtful Dog, Noble / Gas Qtrly, Santa Clara Review, cahoodaloodaling, Watershed Review, The Coachella Review, The Coil, and others. A 2017 AWP Intro Journals Award nominee, she is currently working on a collection of essays in Nacogdoches, Texas.

*Townsend’s non-fiction “Shattered Self-Portraits in the Process of Restoration” appears in Issue 42.1 of Cream City Review.

09.20.2019

Results of the 2019 Summer Prize in Fiction and Poetry

Results of the 2019 Summer Prize

in Fiction and Poetry

We’d like to thank everyone who submitted to our inaugural Summer Prize in Fiction and Poetry. Without you, this would not have been possible, and we are grateful for your participation and trust in our journal. Please join us in congratulating the winners, runner-ups, and finalists of the 2019 Summer Prize!

Winner of the 2019 Fiction Prize selected by Ramona Ausubel:

“The Pig Queen” by Sheldon Costa

Ramona Ausubel says, “’The Pig Queen’ delighted me with its strangeness and discomfort coupled with precise imagery and funny lines.”

Runner-Up of the 2019 Fiction Prize selected by Ramona Ausubel:

“Structural Report” by Debbie Vance

Ramona Ausubel says, “’Structural Report’ is also full of surprises and very thought provoking.”

Finalists:

“Hannah Vechter and the Mockup Man” by Robert Long Foreman

“The Beasts are All Around” by Laura Price Steele

“Renewal” by Adam Byko

“The Witch’s Tooth” by Kate Felix

“The Blessing of the Animals” by Caitlin Rae Taylor

“Euphony” by Natalie Villacorta

Winner of the 2019 Poetry Prize selected by Aimee Nezhukumatathil:

“My Mother Tries to Teach Me How to Garden” by Hannah Dow

Aimee Nezhukumatathil says, “This poem demonstrates how a whole life can be unearthed in the fecundity of a garden. So much richness found in these stanzas, especially in the turning over of word origins, all for it ending with a magnificent last sentence that I haven’t been able to stop thinking about for days.”

Runner-Up of the 2019 Poetry Prize selected by Aimee Nezhukumatathil:

“mountains before mountains were mothers” by Aimee Herman

Aimee Nezhukumatathil says, “This poem’s heartbeat resides in the thrum of its footnotes, fastening bright connections between the “mathematics of your body” and the body as landscape in unexpected and elegant ways.”

Finalists:

“I looked up one day” by Matthew Baker

“Body” by Alana Baum

“The Water, the Truth, the Water” by Stacey Balkun

“Agoraphobia” by Janine Certo

“Only Once Driving in Cincinnati” by Kirk Schlueter

“Rapids” by Tyler Dettloff

“The Wolf as Pick-up Artist” by Emily Cole

“I wrapped the animals I skinned around your hands and neck” by Jacob Lindberg

* * *

Thank you all again for your wonderful work. Be sure to keep an eye out for our Winter Issue 43.2 to read these winning works!

*Banner art: from Gabriel Silva’s “Gold 1”, which appears in Issue 42.2 of Cream City Review.

09.16.2019

“Some Thoughts on Motherhood, Daughterhood, and Water” by Gail Aronson

Some Thoughts on Motherhood, Daughterhood, and Water

by Gail Aronson

Once a man approached me while I was reaching up to a high shelf in a used bookstore. He said unrepeatable things, and then asked me if I enjoyed sex. The employee behind the front counter intervened and these two men had a conversation, while I leafed through pages, pretending I’d stopped paying attention. When the bookstore employee said to the other man he couldn’t “do that” (that meaning verbally harass me) the other man replied, “but look at her, she’s beautiful.” (Sidebar, I’m not beautiful at all, just a woman.) During this conversation I had a dissociative moment, as if I’d just submerged myself into water and the edges were fuzzy—I was somewhere else. I realized these men were talking about me but not to me, as if I wasn’t there, as if I wasn’t a person at all. There have been plenty of other situations by virtue simply of being a woman that I’ve felt more endangered or disrespected. But this conversation struck me with a sense of invisibility.

At this time in my life, I worked with children. One child always remarked that I looked like his mother. As a nanny, other mothers often told me—while walking a stroller down the street or opening my arms to this toddler and all of her buoyant joy as she bunny-hopped from the edge of the YMCA pool and into my arms—that my charge looked just like me. For a woman of age with children in tow, motherhood was assumed.

There is something I struggle to describe that feels mechanical about daily life. Necessary habits of walking down the same streets, drinking from that particular coffee mug, coming up to the wind and rain against my cheeks as I have before. Our actions are filled with circles, and our minds circle back to those repeated circular days, of rising and falling back to sleep again.

When I wrote “The Only Daughter on the Coast of Mothers” I was captivated by the expected roles of womanhood. I wished to play with an imagined future reality in which a woman comes to know herself by being surrounded by what she isn’t. I wanted to remove the personal memories we associate with our upbringings, to illustrate a space in which women exist without men, but are still performing the cultural norms of what came before. Roles we inherit often emerge from this learned automation, doing things as our mothers once did simply because that’s the way we came to know how to do that thing at all. Can mothers mother without daughters? This, logically, seems like a silly question with an easy answer. I wanted to push beyond the factually apparent. To impress upon the everyday something less usual and mechanical that contributes to my own sense of invisibility, an atmosphere distant as the sea with just as much of its substance and complexity inside, underneath.

Of course, I am a visible person living my life in the world, just like everyone else. I am a woman, a daughter. An inner life can be difficult to reconcile with reality and the way others see you. Within the surreal conceit of a coast of mothers and a single daughter who mysteriously wash up to its shores, I hope the boundaries between the interior dreamlike states and exterior reality begins to muddle and melt away.

For me, I can’t separate a sense of complicated personhood from gender. My stories often include, only or mostly, women-identified characters. Not that I dislike men. In reality, the bookstore employee did exactly as any thoughtful, kind person would do. It isn’t easy to intervene, to defend a complete stranger. I don’t blame him that, in the moment, my life felt somehow robotic, my personhood invisible.

That the repetition of everyday life can begin to feel like a kind of automation seems inextricable from how the reality of lived experience is infected and skewed by capitalist culture. Street signs repeat and the lines between who we are and how we can create ourselves through material things naturally blurs. If, as human beings, we are to change or be changed by our own creations, I wonder what is next for humans as we evolve with the earth, which we continue to ruin. An earth we continue to treat as a thing rather than as a living, breathing home. As the atmosphere is altered, how will we change? I hope that the story might subtly lean into this without a direct critique. I often think about our world of capital and how the objects of our lives might encourage a reframing of commodity.

What is a woman, a person, when seen from a distance?

Mother. Daughter. And so on.

When I am most myself, as a writer and (mostly) as a person, I am drowning and floating all at once. Away from linearity, inside the feedback and fuzz, a muffled thing you strain to understand, and yet, it draws you in.

My mother wanted, always and without exception, to be a mother. Or this is how her story goes, how she chooses to tell it. She had me and I became an adult daughter. A nanny at the time, I was also a writer-woman-person at the YMCA pool with this impossibly perfect little new life. And into that momentary nothingness, dipping underneath the waveless not-so-deep water with a child who is a girl who will be a woman, and most of all who is not mine—these are the kinds of palpable and otherworldly moments – I cherish these the most.

*

Gail Aronson is a fiction editor for Omnidawn Publishing and her work recently appears or is forthcoming in Nat. Brut, Midwestern Gothic, The Adroit Journal, The Offing, Dream Pop, and elsewhere. She lives and works in Pittsburgh. Find her online @gailaronson. Aronson’s fiction “The Only Daughter on the Coast of Mothers” appears in Issue 42.2 of Cream City Review.

07.16.2019

“Flash Is Not” by Jonathan Cardew

Flash Is Not

by Jonathan Cardew/ @cardewjcardew

I am a flash fiction writer, which means I write flash fiction. When I say this to people, they usually ask me what flash fiction is and I oblige them with an explanation. It’s very short fiction. It’s like a paragraph or a page. A flash. They nod in acknowledgement. Oh, they say. Oh, right.

It’s the qualifier, of course. The flash bit. Why specify? And I don’t always—most of the time, I just say I write fiction; I’m a fiction writer; I’m a fiction writer of works of a certain length.

So the flash bit is a justification? Or a badge of honor?

I decided to hit up Twitter, asking in my tweet to finish the sentence: “Flash is not…”

I don’t know why I flipped the question to a negative; why ask what something is not? But it seemed appropriate since flash fiction thrives in negative space.

The following are twenty-two tweet replies, in no particular order, finishing my sentence and attempting to answer that question in a different way:

Flash is not comfortable (@tabethanewman)

Flash is not timid (@wreffinej)

Flash is not your grandfather’s nose hairs (@rgvaughan)

Flash is not plodding (@Christopher_All)

Flash is not written to please anyone (@taniahershman).

Flash does not settle in; it doesn’t settle at all (@fabulistpappas)

Flash is not waiting (@VeronicKlash)

Flash is not to disrupt the flow of what it’s not, but I have a pressing question about what it is… reading for a lit mag and flash coming in 5-6 pages long doesn’t seem, well, flashy. Thoughts? (@bronwynnhdean)

Flash is not compliant (@melostrom)

Flash is not a boring rambling snoozefest (@ingram_wallace)

Flash does not seek to explain itself (@Jayne_Martin)

Flash is not devoid of depth and emotion (@laurabesley)

Flash is not meretricious (@Robcodbiter)

Flash is not a poem (@karjon)

Flash is not kind of a poem (@laurabesley)

Flash is not feeble (@melostrom)

Flash is not a matter of fewer words. It’s not an anecdote or a sketch or a vignette. It’s a much longer story that is compressed and written with a lot of words that you just don’t happen to see (@francinewitte)

Flash is not to be underestimated (@writingcircles)

If flash is not a vignette, when can you write a vignette? Poor maligned vignettes. I feel they need a home, recognition, tlc. Or are they the juvenile frame for flash? (@wordpoppy)

Flash is not welcoming (@steveXisXoc)

Flash is not very long (@nlordlancaster) A banana isn’t flash fiction (@samaveris)

[Tweets republished by permission of the authors]

*

Jonathan Cardew‘s stories appear in Passages North, Wigleaf, JMWW, Cleaver Magazine, People Holding, and others. He edits fiction for Connotation Press. Originally from the U.K., he lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.