My Way Alone, by Chayele Grober (Part I)

Originally published in Yiddish as Chayele Grober, Mayn veg aleyn. Tel Aviv: I. L. Peretz Publishing House, 1968

Translated and introduced by Violet Lutz; edited by Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel and Alyssa Quint

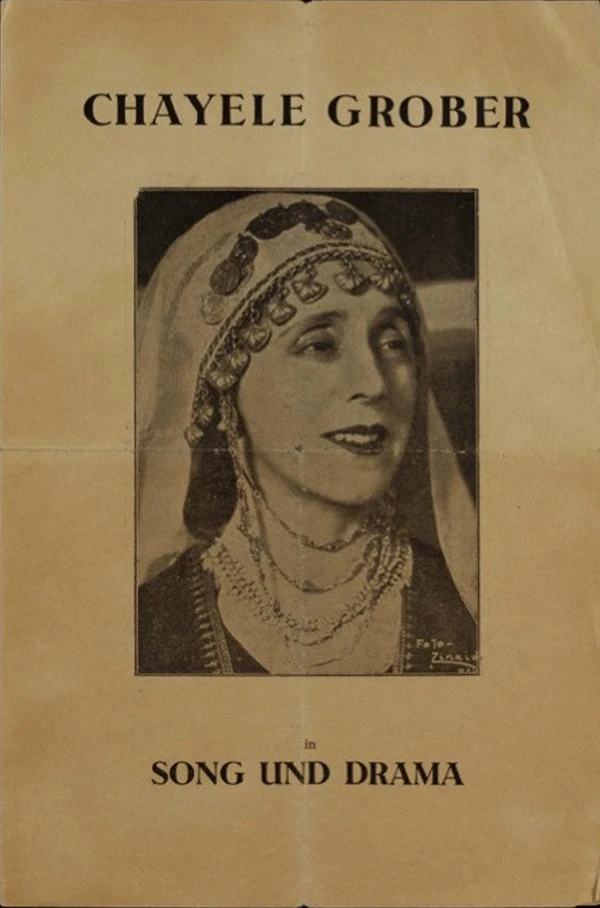

Chayele Grober (February 16, 1898 – December 10, 1978) began her stage career as an actress with the Hebrew theatre “Habima,” from 1917 to 1928. In the subsequent decades, she performed as a solo artist in her own program of song, drama, and humor, in both Yiddish and Hebrew. She toured internationally with great success, appearing in North America, Europe, Palestine (later, Israel), South America, Australia, and South Africa. Born in Białystok (then in the Russian empire), Grober attended a Russian high school and learned Yiddish and Hebrew with private tutors. During the First World War, she and her family were forced to flee their home and eventually arrived in Moscow in 1917. At that time, Nahum Zemach, whom Grober knew from Białystok, was establishing the Habima Theatre in Moscow, and invited her to join. Grober and her fellow actors of Habima developed their theatre art under the guidance of Yevgeny Vakhtangov, a brilliant Russian theatre director who had been a student of the famous Konstantin Stanislavski.

In New York in 1928, following two years of touring with Habima through Europe and the United States, Grober left the troupe and began developing her own solo program, integrating Yiddish literary material with folk songs and Hasidic melodies. She first performed in New York and then embarked on a tour of the United States and Canada. During a stay in Montreal, she formed what became a lasting friendship with Hananiah Meir Caiserman, a Jewish community leader and activist, and his wife Sarah Caiserman. Grober subsequently made her home in Montreal and became a Canadian citizen. Through the Caisermans, she met the journalist Vladimir Grossman, who managed her first European tour, in 1930–31; the two married in Montreal in 1937. From 1939 to 1942 Grober led her own dramatic studio in Montreal—the Yidishe teater grupe (Yiddish Theatre Group; YTEG). In 1966, she moved to Israel.

Grober was the author of a play, Af fridlekher erd (On Peaceful Soil), which was performed under her direction in Melbourne, in 1957, by the David Herman Theatre Group at the Kadimah. In addition, she published two memoirs. The first, Tsu der groyser velt (To the Great World; Buenos Aires, 1952), concerns her early life and her years with Habima. The following excerpts are taken from her second memoir, Mayn veg aleyn (My Way Alone; Tel Aviv: I. L. Peretz Publishing House, 1968), which focuses on her path as a solo artist, while also conveying episodes from her earlier life, especially related to her training as an actress with the Habima theatre.

A New Beginning

Artists live in a world of dreams. That is the beginning of the process called creation. I lived out my childhood years in dreams. The first dream (indeed, in sleep) that I saw as a presage of something in the future came to me before the outbreak of the First World War. I spent many summers of my childhood in the little town of Milejczyce (in the Białystok region). The summer of 1914, our summer residence was right near a pine forest. In the hallway of our summer home was a little ladder leading up to the attic. One night that summer I saw this in a dream: I clamber up the little ladder, and the higher I reach, the bigger the ladder becomes; I climb and the ladder grows, and I am already so high that I can barely see the earth under me. Suddenly, the ladder begins to rock, and then rocks more and more forcefully. I feel that in an instant I will fall and be shattered… In that instant, my deceased grandmother appears before me, and I hear her warm voice saying: “Do not be afraid, my child. Go, climb higher. You won’t fall!”

I woke up.

On a frosty night in 1917, when Moscow lay deep in snow and the Muscovites—all wrapped up in their heavy furs—were lumbering around like bears, I entered a dark hallway, and the dimly lit stairs led me to a small, unheated room that was filled with young people. In that very room, Nahum Zemach sowed the great idea of the first Hebrew theatre, Habimah (“stage”) and on that frosty night the genius of the modern Russian theatre, Vakhtangov, ignited the young group with the fire of the highest creativity.

Those are the steps on which I began my long, hard way upwards. More than once over the decades my ladder shook. More than once I felt that any moment now, I would tumble down and be shattered. And always in such moments I would hear my grandmother’s warm words: “Go, my child, climb higher—you won’t fall!”

In the years 1915, 1916, and 1917, there was a mass emigration from the towns and localities that lay close to the German-Russian border. The air was filled with dynamite. On the German-Russian front, anarchy ruled, and on the whole route from the front to Minsk, Pinsk, Kharkiv, Moscow—a complete orgy took hold, with people drinking and carousing, in order to drown out the coming catastrophe.

With the stream of hundreds of thousands of Jews, our little family also arrived in Moscow. We had not brought any of our belongings from home. All that I brought with me was my spiritual heritage and deeply rooted tradition.

I was drawn to the theatre by chance—a friendship with my fellow townsman Nahum Zemach. Zemach invited me to the group that he had organized with the idea of creating a Hebrew theatre. And the group’s teacher, Yevgeny Bagrationovich Vakhtangov, inspired me to song. But my connection with song was not at all by chance. My grandmother and my parents had sung to me and made song a part of me. The first song that I learned from my grandmother was the song about the blimele (little flower) that lies in the middle of the road, and everyone who passes steps on it. My grandmother would end the song with, “See here, they are talking about the people Israel, my child!” My grandmother’s songs always had a moral. After that, the songs of Goldfaden’s operettas began to resound inside me; later, arias from operas and Russian romances. And only then did Yiddish folk songs begin to reverberate in me. Along with those, traditional holiday songs and prayers were always sung at home. In this way, little by little, I developed a passion for expressing myself in song.

I heard folk songs for the first time from poor people in our courtyard and also from the young women servants who worked for us. I was already twelve or thirteen years old when I went to the theatre for the first time. The songs had a greater effect on me than the dramatic conflict. The idea of appearing on the stage, of playing in the theatre, was not just something that I dreamed about, considered and decided upon; rather, I simply felt—and very precisely—that this was the purpose of my “being” in the world. For that reason, when I was all of fifteen years old, I said to my mother with such surprising certainty: “I will be on the stage.”

What form my artistic inclinations would take I did not yet know, or decide. The stream of life led me in 1917–18 to Habima. But in 1928, after I had been with the Hebrew theatre for ten years, I reflected on and analyzed those ten years of experience with Habima, and decided to begin my way alone.

I prepared for my way “alone” while I was still with Habima, by taking voice lessons at the same time with professors of the Moscow Philharmonic. I learned Yiddish song from the composers Joel Engel, Mikhail Gnessin, and Moshe Milner. The two great schools—the dramatic and the musical—were the foundation upon which I built my one-person theatre. I combined the dramatic etude with Yiddish song. And, in fact, I called my program “Song and Drama.”

The ten years in the theatre were years of dreams, years of belief, and of despair—and even stronger belief: those were the turbulent years, when Russia was fighting for freedom, and we were fighting for our existence. Those were years of daring accomplishments, of disappointments and exaltation. It was those years that strengthened in me the conviction that the whole of private life, with all its conflicts, is a minor matter, and that the main thing—the real essence—is theatre. And, as the founder and director of Habima, Nahum Zemach, instilled in me, national theatre. I have Nahum Zemach to thank for my sense of national values and my path as a national artist.

It was not until 1928, in New York, after Habima’s sensational tour in Europe and America, that the question began to rankle my brain: which is to be our national theatre, Hebrew or Yiddish? “הכונו, הכונו ,הבימה בירושלים” (Prepare, prepare, Habima in Jerusalem)—that became the leitmotif. It became clear that Hebrew theatre can exist only in the Land of Israel. The great Jewish world did not understand us. The problem surfaced: what is more important—a theatre for one land, or a theatre for the world, for our Jewish world?

In the course of the last several years, there had been discussions about this question in our theatre—not official discussions, but private discussions that occurred more and more frequently. Always, the spiritual strength of Nahum Zemach had won out. But in New York, when Nahum Zemach decisively separated himself from his theatre—the theatre that he had dreamed up, that he had prophetically prepared for our land—his decision strengthened in me the resolve to leave.

Besides the language question, there were other reasons that impelled me to make this bold decision. Habima was built on the principles of a collective, which means: equality and brotherhood. Unforgettable nights with the theatre genius Y. B. Vakhtangov were devoted to the new forms of collectivism. How painfully Vakhtangov reacted to this disappointment! The ambition of some of the members of the collective to become prima donnas and theatre directors broke the principle of collectivism. And instead of brotherhood, hatred took root. It became hard to breathe in the hostile atmosphere. I left Habima and bravely began my way alone.

Even before I had made my decision, there was talk about it on the Avenue (the center of Yiddish theatre in New York), and immediately I received offers. Through Dr. Mukdoyni, I received an offer from a famous actor to open a theatre in the Bronx. Mukdoyni’s answer was: if she asks my advice, I will tell her not to accept. Maurice Schwartz approached me directly, and was utterly surprised when I turned him down. Maurice Schwartz and his Yiddish Art Theatre were then at their height, and an invitation from him was considered an honor and good fortune. Indeed, I viewed it that way. In that and many other instances, my mother’s logical mind—which I perhaps inherited from her—came to my aid. Logic told me that New York has many good actors, and the Art Theatre has the best; that suggests that Maurice Schwartz needs me merely for “publicity.” It is in the nature of publicity that it lasts only until the first failure. And I was certain that I would experience that failure.

The system of preparing a play, of developing a role, of immersing oneself in the role, requires two things: time and the necessary atmosphere. Neither of those two things could be found in Yiddish theatre in America—not even at Maurice Schwartz’s theatre. It was clear to me that there was no theatre that I could go to, and that I would have to develop a program for myself.

One-Person Theatre

To be on stage alone for a whole program is much more difficult than playing the lead role in a play. It is not a physical difficulty. A solo program requires highly developed concentration, an absolute control, and a well-trained sense of moderation and proportion. It requires the elements of drama and humor. In my opinion, it also demands of the artist a positive relationship, a friendship with the audience. In a play, the actor has direct contact with his partner, and his contact with the spectator is indirect. The solo performer immediately has direct contact with the spectator. I think that is the reason that there are so few successful solo artists.

There are three forms of solo art: recitation, readings, and one-person theatre. Reciters have distinguished themselves much faster than performers in the other forms. These forms of theatre art require the artist’s complete dedication.

Of our Jewish theatre artists, the reciter Herz Grosbard (1892–1994) burst upon the scene in the 1920s. He became famous, and remains today the best in this genre. I believe that is the case because he continued with his own original form. Herz Grosbard possesses a strong voice, a good temperament, and marvelous diction. In addition, he creates a distinct atmosphere with the use of a little lamp that illuminates just his face. He was the first on the Yiddish stage to read for an hour and a half while sitting motionless at a little table.

A second Jewish artist in this genre (in a non-Jewish language) is Berta Singerman (1901–1998), who has had a major career in Argentina. Berta Singerman is truly a legend in all Spanish-speaking lands. More than forty years since her name was first heard, people do not tire of hearing her again and again, even in the same recitations.

In the realm of one-person performances, there have been as of now two great female artists (neither is Jewish): Ruth Draper (1884–1956) in English, and Yvette Guilbert (1865–1944) in French. Ruth Draper develops her material solely as drama; Yvette Guilbert bases everything on song and music. Both play out their scenes without a partner and without props or accessories of any kind. Both are, in the same measure, great artists, and create a complete illusion, as if everything and everyone is there on the stage in real life.

One other actress has embarked on this kind of one-person theatre—the English actress Cornelia Otis Skinner (1899–1979). In her shows, she has brought onto the stage everything used in a theatre—pieces of scenery, costumes for every number, an orchestra, wigs, makeup. But for all that, she has not had the same success as the two aforementioned artists.

The secret of success of those two artists lies in the simplicity of the presentation. The audience likes to feel, to complete with their imagination what has been left unsaid. That means the audience wants and needs to be active—active not only by reacting but also by creating.

The non-Jewish press in Europe and America has often compared my theatrical work with that of Ruth Draper and Yvette Guilbert. To a certain extent that is correct. My programs are built on the same principles, and contain dramatic and musical material. None of the critics has compared me with our folk singers, although my program includes a large number of songs, and as a whole is built on music. That suggests that this kind of art belongs to a different category. The folk singer interprets the song. In my work, the song is interwoven in a dramatic scene or in a story. I seek out the song that corresponds to the mood, the rhythm, of the etude or story. Often the song stimulates the creation of the etude. For example, the etude of the “Vayse toybn” (white doves) by Zishe Weinper came to me through a memory from my childhood years.

In my little town Milejczyce there was a young, gentle, dreamy, modest girl—the only daughter of the rabbi and ritual slaughterer. One summer when we were staying there at our summer place, she told me that in the winters, when none of the summer people were around, she would sit for entire days and evenings, sewing a parochet for the Holy Ark, a mantle for the Torah scroll, or something else. Years later, when the composer Solomon Golub (1887–1952) played for me his music to Weinper’s “White Doves,” the image of that young girl suddenly surfaced in my mind. I could literally sense the snowy blizzard outside the little heated house, and I was filled with a kind of longing. I personified that young girl, and called the etude “Benkshaft” (longing). It remained in my repertoire for all the ensuing decades.

As dramatic material, I included in my first program I. L. Peretz’s sketch “Nokh kvure” (after the burial). The famous composer Joseph Achron (1886–1943) composed music especially for the number, for violin, cello, and piano. In that first program I also included a section called “Hasidic,” and another called “Folk Scenes.”

The Premiere of “Song and Drama”

It took me a whole year to prepare the first program. In that year, I needed to select the material and develop every number. The numbers that took the longest were those that are played out in mime. One has to work on those numbers in the same manner as dance numbers. Every movement has to be developed, so that it goes in rhythm with the music. Once the number is fully ready, it will remain in the repertoire for a lifetime. A number that lasts four or five minutes can take weeks to prepare. In this way, with patience and work, I came to this new kind of performance for me—after theatre and ensemble: one-person theatre. And that is how “Song and Drama” came to be.

In order to try out the first program, I booked a small theatre that had only 120 seats. That little theatre belonged to a famous actor of the Moscow Art Theatre, Richard Boleslavsky (1889–1937), and an actress of the same theatre, Maria Ouspenskaya (1876–1949). My excitement before the concert was not any less than before my premiere with Habima—despite the fact that I had the moral support and friendship of Joseph Achron, who conducted the trio himself, behind the stage; from the director Leo Bulgakov (1899–1948), who prepared the program with me; and from Dr. Alexander Mukdoyni (1878–1958), before whom I had rehearsed each individual number. After the first, successful concert, we decided to book the large theatre of Eva Le Gallienne, which was then on 14th Street.

Soon after I performed my first concerts in New York, I received an offer to make a small tour across the United States and Canada. There was no question of my touring alone, because the American Jewish public loves “variety” shows… We put together a program for three. The first to present Jewish dance in a genuinely artistic form was my colleague Benjamin Zemach (1902–1997), a brother of Nahum Zemach, the founder of Habima. He was the most fitting artist for such a program. As pianist, we invited Pola Kadison. The Kadisons were a famous family of artists. The father, the mother, and [another] daughter, Luba, were among the top artists in the Vilna Troupe. Pola Kadison—musically talented—became a well-known and popular accompanist in New York. For me, Pola became not only my piano accompanist but also a kind friend such as one seldom meets in an Americanized artist family.

European Tour

On June 13, 1930, I took a ship from Montreal to Paris. Hanan (Hananiah Meir) Caiserman (1884–1950) accompanied me to the ship, and handed me a little slip of paper with the name of a respected Jewish journalist. He told me that I should absolutely contact him and propose that he take on my European tour.

The ship left the Canadian shores in the middle of the night. For the first time in my life, I was alone on the open sea. The waves carried the ship faster and faster onward, and the full moon in that June night drew all my thoughts to the past. During those three years I had settled into life in New York: I had grown fond of America, and left behind there three years of my youth, years that would never come back. The years would never return, and neither would the dream that had become reality and was now dissolving into yet another dream…

In the French port of Le Havre there were hundreds of people waiting to greet relatives and friends from the other side of the ocean. No one was waiting for me, and no one greeted me. Where I drew the strength to go out into the world alone I cannot explain even to this day. I hardly believe it had anything to do with realistic, clear-headed thinking. It was simply a drive, and a deep belief.

Vladimir Grossman (1884–1976) is a well-known Jewish journalist. He was the editor of the Yiddish newspaper Parizer Haynt (Paris Today). In that summer of 1930 his work on the newspaper was already behind him, and he was preparing to publish a journal. There was no financier to support the journal, and he himself had no capital. It was a hot summer. The Parisians had all dispersed for vacations and pastimes, and I suddenly alighted there, as if from heaven. I understood this only later on. From the beginning I thought it was nonsense to propose to a journalist with his reputation to take on a tour with an actress who had only just begun a concert career. So it was with this sense of uncertainty that I met with V. Grossman, accompanied by my colleague Shoshana Avivit (1901–1981).

We met at a bistro. In view of the extreme heat we ordered soda water. In Paris one does not pay for water, only for juice. When we had quenched our thirst and were getting up to go, our cavalier said to us in Russian: “Well, girls, now pay up!…” On that phrase, I sensed that now was the right time to talk to him about managing my tour.

Grossman took just two weeks to put his business affairs in order, pack up his library and other things and store them away in a secure place, and prepare for our travels. He arranged for me to stay in a pension in Fontainebleau. Although I made clear to him the extent of my capital, he purchased two rail tickets for a sleeping car.

The theatre season in Europe begins in September, so we decided to stay for the summer months in the Polish seaside resort city Sopot. My “manager” believed that there one would be able to give a number of concerts through the summer. On our first day there, when I went out on a walk, I felt, on that hot day, a chill in all my bones. In those elegant gentlemen and ladies I could not recognize our Jews. The air was filled with the sounds of the Polish language. With my Yiddish and Hebrew I felt out of place and a little lost.

How great was my surprise when the room in “Casino” filled up long before the beginning of the concert. People proposed a many times higher price for standing-room tickets. We did indeed have several successful concerts in Sopot. And that was the beginning of my first European tour.

Warsaw is the nearest Jewish center to Sopot, but I insisted that we should begin the season in the Latvian capital—Riga. It was from there that, years before, I had begun the tour with Habima. I believed that the Riga press and public would still remember my appearances with Habima. The response in Latvia quickly circulated in Lithuania and Poland. “Song and Drama” became a sensation. In the theatre season of 1930–31, we worked our way through Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Poland, and at the height of the 1931 season, we arrived in Paris.

For Grossman, my concert was not his first such experience. Long before we met, he had taken the Moscow Art Theatre on a tour through Scandinavia. For a short time he had led the Danish Theatre. He was a specialist in “publicity” and he had a wide European scope. He presented my Yiddish-Hebrew program like the great international concerts. In Paris he decided to book the concert hall “Gaveau.” When I went to see the stage, and heard that the great Russian singer Feodor Chaliapin (1873–1938) had often appeared there, I became agitated. I asked my “manager” to book a smaller hall, but Grossman will not be dictated to, and so it remained “Gaveau.”

The hall was full, just as it would have been at the “Nowości” in Warsaw. The French press compared me to their only performer in the same genre, Yvette Guilbert. With that we ended the season, and remained in Paris for the entire summer.

The next season, we began from Belgium. In those good years, Antwerp was a great Jewish center. After Antwerp came Brussels and Liège. Little by little, I began to comprehend how big our Jewish world was. In little Belgium, we gave innumerable concerts.

Palestine

I left Belgium at the beginning of spring, and disembarked from the ship in Haifa before Purim. Those who knew about my arrival included my managers, Popuch-Bregman; the intermediary, my Białystok friend Moyshe Furie; my brother Elinke and his family; and virtually the whole of Palestine. But everyone arrived to meet me at the port when I was already at the hotel. An Englishman whom I’d met on the voyage gave me a ride to Tel Aviv. A chauffeur with a car was awaiting him at the port. His vehicle remained at my service almost the entire time that I was in Palestine.

The route from Haifa to Tel Aviv looked like a desert. The land was dried out, barren. Half-veiled Arab women, with large earthen jugs on their heads, strode rhythmically to the faraway well to draw a little fresh, cold water. On the entire almost four-hour-long drive, there was only a single little Jewish shop, where we drank our first cup of coffee in the land.

The impression that Tel Aviv made on me—as it would on anyone coming from Moscow, Paris, or New York—was that of a large village. The sun beat down and people strode slowly, heavily through the sandy streets. The windows of the little houses were open, and from somewhere came the sounds of an old phonograph record of Yossele Rosenblatt.

The only large hotel in Tel Aviv, as I remember it, was the Palatin. The waiter who came over—I should say, quietly stole over—was wearing a long Arabic garment with a white chalma (turban) on his head. He secretively spoke English, but he served authentic Jewish dishes. The atmosphere in the hotel and in the dimly lit dining room was my second disappointment in the land. I had had my first disappointment on the drive from the port to Tel Aviv, when I glimpsed, in the middle of a field, a horse and not a donkey.

Only after I had finished eating and had rested (not so much from the trip as from the first impressions) did my brother Elinke arrive, and after him, my managers and their friends—all of them having now returned from Haifa port… As they entered, so did the breath of the Land of Israel.

Back then, just as today, my Israelis had no interest in asking about news. Rather, they themselves had a lot to tell. They told about the moods in the land, about the various social-political directions, about the strengths of the kibbutzim. I began to sense the new atmosphere.

While I was still in Brussels, immediately upon deciding to travel to the Land of Israel, I had reworked my entire program in Hebrew. When I arrived there, as soon as I became acquainted with my pianist, Sonya (Sarah) Goland, and began to prepare my concert, I also began to visit the Yemeni Jews who lived in Tel Aviv. Only among them could I learn and absorb the authentic Eastern pronunciation. The result of my contact with the Yemeni women was the following: after my first concert in the Mograbi Theatre, people came to me to say that the great poet Hayim Nahman Bialik (1873–1934) had expressed the view that in the time since Habima had been in the Land of Israel, not until today had he heard an authentic, good Hebrew. Bialik undoubtedly meant by that the pronunciation, because Hanna Rovina (1888–1980), for one, could speak Hebrew better than I could—but their Hebrew sounded Russian.

The stage in the Mograbi hall that evening looked like a flower garden. Flowers were already then the pride of the Israelis. Many of the songs in my program immediately circulated among the people, so that when I visited the kibbutzim people there were already familiar with the songs and knew what to call out. The public received me with respect and affection. Wherever I went, I encountered joy. Such were the Jews of the Land of Israel at that time. There wasn’t yet the snobbery, the chase after the golden calf, the fashion houses. Men wore short trousers and unbuttoned shirts, women—white blouses and dark skirts. People wore sandals, or went barefoot. Purim was prepared and celebrated in exactly the same way as in my little town Milejczyce. For that reason alone, I became beguiled by everything and everyone.

After being in the land for a few months, I began to search out material for a section of my program that would reflect the East, not merely in the language but also in the atmosphere. It was somehow difficult for me to concentrate, and I decided to travel to Nazareth. That was a daring decision, because I had heard indirectly that if people learned that I had been in Nazareth, I would be boycotted.

I could not resist the temptation. Through my friendship with the Englishman I’d met on the voyage, I arranged to drive to the forbidden village. There, as if by means of a spell, I journeyed into the old, legendary East. Night fell. The moon appeared from behind the mountains. In the empty, narrow little alleys, a thousand-year-old stillness reigned. Camels with loads on their backs strode rhythmically over the mountains, the shadows of the Arabs by their side. The air was filled with the thinnest tinkling sounds of the little bells hanging from the camels.

It is remarkable: actors attach so much importance to makeup, costume, and stage scenery, when in reality one needs only light and sound in order to create the necessary atmosphere. The atmosphere and the rhythm of Nazareth inspired me to create a set of Yemeni and Arabic songs. Later I performed that set in Arabic costume, and employed the special little bells.1

Scandinavia

Grossman insisted that we visit the Scandinavian lands before leaving Europe. The four Scandinavian countries—Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland—were absolutely foreign to me. But Grossman had lived in Denmark during the years of the First World War. He was very familiar with Jewish society in the Scandinavian lands, and had ties with the press there.

We began the Scandinavian tour in Stockholm. Of the Jewish communities in Scandinavia, Sweden is the largest. The evening took place in the municipal concert hall. The Swedish press came, and also Swedish actors. After the concert we were surrounded by the local Jewish society. I arrived in what was for me a foreign land and, a short while later, took my leave from people who had become my friends for a lifetime.

The reviews of the Swedish press assured our success in Denmark. Before traveling to Denmark, I wanted to introduce myself in my imagination to a Danish Jew who could engage with an authentic Jewish concert. And, in fact, a delightful surprise awaited me there. On the first morning after our arrival, we had an unexpected visitor. A tall, handsome, very elegant man, and a charming young woman entered our hotel room, with a large bouquet of red roses. The man took off his bowler hat and introduced himself: “I am Chaim Ritterband, a tailor, and this is my Chavele. We welcome you to our country.”

Chaim Ritterband was a tailor by profession, but a singer in his soul. He had brought with him from home a wellspring of folk songs. Under the influence of those songs, he also composed music himself. But he was not satisfied with composing, collecting, and publishing songs. He prevailed upon a famous Danish folk singer to incorporate into her repertoire our Jewish songs. Years later, that singer performed in New York for a group of Danish compatriots, and there, too, she sang those songs that Ritterband had brought to her.

Ritterband was a proud, spirited, warm-hearted Jew. As a young man he had left anti-Semitic Poland, and he perished in Denmark during the dark days of Hitlerism. I consider it a special privilege that life has brought me together with so many marvelous people, interesting personalities, great artists—with ordinary people. I cannot name a single land I visited where I didn’t meet someone who would remain in my memory for a lifetime.

Continue Reading Part II of My Way Alone.

Notes

- Translator’s note: By the time Chayele Grober left Palestine, she had been invited once again to tour Lithuania and Latvia. After that, she performed in London. Subsequently, she toured in Romania, in 1935, and then once again in Poland, in 1936. In view of the increasingly alarming news from Nazi Germany, she made plans at that point to return to New York, and to Montreal.

Article Author(s)

Violet Lutz

YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH

Violet Lutz is a processing archivist at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. She holds a PhD in Germanic Languages and Literatures from the University of Pennsylvania.