Interview: Alicia Svigals and Donald Sosin on Their Film Score for The Ancient Law

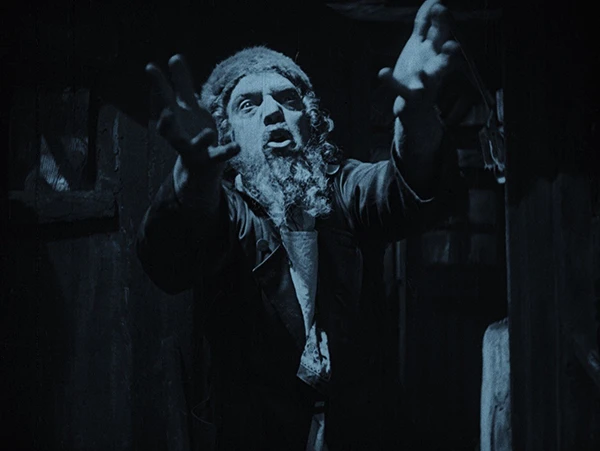

A 1923 WEIMAR-ERA German film, Das alte gesetz (The Ancient Law), directed by E. A. Dupont, has only recently been literally pieced together after decades of dusty neglect. The movie tells the familiar story of a backwoods Jewish boy whose talent leads him to show business success and possible romance with a well-placed Gentile woman. The question is: will he a pay a price for “abandoning” his people and hometown girlfriend? The answers vary, across a number of films. The answer is: yes, big-time, in the 1940 Yiddish-American melodrama Der vilner balabesl (Overture to Glory), where the star Moishe Oysher expires after singing “Kol Nidre.” But there are other options. In another Yiddish film, Dem khazns zindl (The Cantor’s Son, 1937), the same Moishe Oysher ditches the American girl who helped him rise and goes back to Europe, reuniting with his sweetheart and community. The topic of the showbiz turncoat is not limited to the in-house Yiddish crowd. Das alte Gesetz was a general-release film, as was 1927’s Hollywood version of this archetypal plot, The Jazz Singer, starring Al Jolson as semi-himself. That film allowed its hero to have his career, sing “Kol Nidre,” and get the girl, unlike the 1925 play by Samson Raphaelson on which it was based (itself adapted by the author from his own 1922 short story, “The Day of Atonment”), which ended on a question mark.

It’s revealing to pair the Weimar-era Ancient Law with another 1920s German-language film (from Vienna), Ost und West (East and West), for which the young American star Molly Picon was imported to tell a tale of reconciliation between the old ways and the assimilated Amerikanke via the cultural bridge of Vienna and enlightenment. An almost unbearable irony sets in while watching interwar optimism about the fate of the Jews in German lands, but there it is, a beautifully acted melodrama with a happy ending in which the actor can have stage stardom, his now urbanized shtetl sweetheart, and even the love of his reconciled rabbi father all at once.

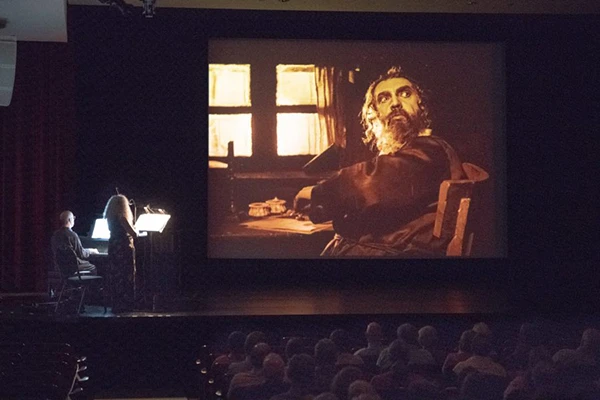

To speak to today’s audiences, what The Ancient Law needed was an intelligent, well-executed film score to carry viewers across the multiple social settings and characterizations, rife with internal conflict. An ideal team has done just that. Alicia Svigals, whose work on another silent film, The Yellow Ticket, was widely praised on her multi-city tours, combined with Donald Sosin, a titan of early-cinema scoring, to produce an unusually supple, accurate, thoughtful, and moving score. I saw it live at Lincoln Center and then on video, which only intensified my admiration for the soundtracks’ craft, accuracy, and emotional charge. To date, the Svigals-Sosin duo have performed it live some fifty-five times, to universal acclaim.

Our interview was wide-ranging and is excerpted below. I was interested in some key issues: the combination of pre-composed music with improvisation, the placement of recognizable classical music compositions, how music constructs shtetl life, as opposed to the streets and palaces of Vienna, and how duality literally plays out in the mind of the protagonist Baruch.

MS: How did you come to this project?

DS: I played for this film maybe twelve years ago with a lousy-looking print—it looked awful, it was very dark. The film was not in the proper order. People didn’t know what to make of this film. The director, Dupont, had a big reputation based on two other films: Variety with Emil Jannings and Piccadilly with Anna May Wong. Those are fantastic films. Deutsche Film approached me in 2017—I had done half a dozen other films for them. I heard Alicia play The Yellow Ticket—I literally ran up to her and said: “I have this project for you.”

MS: I don’t know if you’ve done other ethnic-themed films?

DS: I have a long association with Sharon Rivo and National Jewish Film Center, so I’ve done a number of Yiddish films.

MS: Do you pre-compose those?

DS: I have a few themes and improvise. Unless I’m working with other people, it’s more fun (and less work) to improvise.

AS: But this is the first Jewish film you’ve recorded. And I’ve done exactly one before this.

DS: But I wrote my own Jewish opera, “Esther.” My mother is a Yiddish speaker and translator. My grandmother grew up in Ukraine and spoke Yiddish as well as Russian. I learned a lot of Yiddish songs at a very early age and have sung them all my life.

MS: You have an insider view doing this work.

DS: Yes, and I went through years of Sunday School and made several long trips to Israel.

MS: How does that kind of intimacy play out in what you did for this film?

DS: The milieu of the beginning of the film is so specific to the sound world of eastern European Jewry, what they use for their holidays: Purim, Pesach, Yom Kippur.

MS: How do you see The Ancient Law as different from The Yellow Ticket?

AS: For The Yellow Ticket, it’s not really improvised. There are similarities—leitmotifs not just for people, but ideas, like romantic love. I gave Marilyn Lerner lead sheets and she filled them out. Whereas Donnie composes on the spot—to me it’s like a miracle.

MS: Did you go to actual sources for inspiration?

AS: Before we went to the studio, I wrote a bunch of “klezmer” style tunes and nigunim. It’s my fakelore—it sounds old, but I wrote it. I wrote the opening theme, the nign, which became the leitmotif for the idea of “tradition,” which both nourishes and suffocates. I wrote some freylekh Purim music for the Purim scene. I wrote a dirge-like nign we used for the rabbi’s illness scene. I also wrote a Viennese-style waltz which becomes the leitmotif for the Habsburg court, the archduchess, and the wider world Baruch wants to be part of and that’s pulling him away from the shtetl.

It was a beautiful collaboration, because Donnie improvises stuff on the spot that sounds like Beethoven and Schubert, tunes that develop my material and take it to different places.

DS: And writing piano arrangements of this material. In the film we’re working on now, we’re doing very detailed violin and piano arrangements in the Viennese classical tradition.

AS: Some of it is composed, and a good half of it is improvised as we do it each night, and the more we go on, the more the improvisation weaves into the pre-composed themes and becomes like leitmotifs. Donnie interweaves stuff that expresses the tension of the situation, which is very hard to do. He changes the mode, and I jump in. We have Passover, Adir Hu, Seder snippets.

MS: And then there are literal quotes from Schubert and Beethoven.

AS: As Baruch is in the dressing room, he weaves together the Beethoven theme (from the slow movement of the 4th Piano Concerto) and “Kol Nidre,” because he’s trying to daven. That’s not on the DVD—we do it live.

DS: It’s the overlap of Beethoven with the first four notes of “Avinu Malkenu.”

MS: In an average performance, what’s the percentage of improvised vs. pre-composed music?

AS: There’s five to ten percent of actual Beethoven and Schubert, and of the rest, half is pre-composed and half is improvisations.

DS: I think there’s less and less improvisation.

AS:. We’re getting more codified, but Donnie had this great idea. When Baruch does his audition for the theatre director, I should do an improvised over-the-top romantic cadenza, and that got pretty codified, but now I keep improvising on it like they did in the day.

DS: When Baruch is doing the death scene from Hamlet, we’ve got a mood for it, from the Beethoven concerto. I improvise the scene when Baruch is going to leave the shtetl.

AS: We have to go with the mood. Another leitmotif I did is for Pick (the intermediary figure between shtetl and city)—we improvised it and it immediately got codified. Then Donnie brought in the Schubert B-flat Major piano trio as a love theme for Baruch and Esther.

DS: And we’ve started using the last movement of Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet that could become a theme for Baruch by starting nign-like and then morphing into Schubert.

AS: Because Baruch is a fish out of water.

MS: What about the accordion in the score?

DS: In live performance I have a synthesized accordion, but on the recording, we’ve had percussion and bass. Next we’re going to have a clarinetist in March, and then I added the sound of the Austrian marching band. It’s all digital samples.

MS: Do you think of these themes as actual leitmotifs in the Hollywood sense?

AS: Leitmotif light.

DS: Pick has a theme, Esther doesn’t have a theme per se.

MS: How many times have you done this?

AS: 55 times. We have 50 performances recorded.

MS: What’s your next project?

AS: We’re working on City Without Jews now and two more in the pipeline.

DS: We’re considering doing The Cohens and the Kellys. There was a quartet of really good musicians that scored it in the UK, so we’re waiting a while to do our version. It could have Irish fiddling.

DS: And check out the Jewish-Irish connection, of which there’s a lot.

MS: It’s becoming a cottage industry.

DS: And if anybody dies, it’s a kaddish industry.

DS: People flip over this film—they come up to us and say “unbelievable.” It’s astounding how meaningful this film is to the older generation, but we’ve also done it for college audiences and Yiddish vokh.

AS: Our funder, Cynthia Walk of The Sunrise Foundation for Education and the Arts, underwrote a Yiddish version, done by Arun Viswanath, so now it’s a Yiddish film.

I like the way the interview ends with the idea of this kind of project being cyclic. Svigals and Sosin’s work resonates with early Yiddish musical theatre practice. In those days, pit orchestras tended to combine the pre-composed with the improvised in ways we can’t quite measure now. Full scores were rare; a conductor passed out instrumental parts and the ensemble figured out how to proceed, as marginal annotations in manuscript sources indicate. And like Sosin, the conductors and arrangers had extensive background in both Jewish upbringing and, often, classical training, as well as on-the-job experience in a variety of formats. Adaptation from non-Jewish sources, as in The Ancient Law, was widespread. I find it heartening that Yiddish and Jewish-themed cinema of the past can echo the golden age of worldwide Yiddish theatre.

Article Author(s)

Mark Slobin

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY

Mark Slobin is an American scholar and ethnomusicologist who has written extensively on the subject of East European Jewish music and klezmer music, as well as the music of Afghanistan, where he conducted research beginning in 1967. He is a Professor of Music and American Studies at Wesleyan University.

In 2017, Slobin was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.