Dragging the Netherlands into a Global World: Yiddish Theatre and the Ansky Society

Unlike most interwar Yiddish-speaking communities in places like New York, Paris, Moscow, or Buenos Aires, Yiddish speakers in the Netherlands never established a permanent Yiddish theatre or daily newspaper, cultural institutions that mark an immigrant community as rooted in a particular place. It did, however, establish the Ansky Society, which had a well-known drama group, a small but important library of books donated by its members, and ultimately served as a place for immigrant social and cultural community. The Ansky Society also started a small hectograph called Friling (Springtime), a newsletter for the Society’s members.

Whereas early modern Ashkenazi Jews established Yiddish printing houses in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, making the city a central of the early modern Yiddish cultural world, the eastern European Yiddish speakers who began arriving there in 1881 saw the Netherlands as a way-station. Native-born Dutch Jews, too, saw Yiddish-speaking migrants as needing assistance to reach their final destinations, not as potential community members. During World War I, when Belgium expelled many Yiddish-speaking Jews as “enemy aliens” from the Austro-Hungarian empire (with which it was at war), quite a few ended up across the border in the neutral Netherlands. The end of the war meant that they could return to Belgium. Some chose to stay in the Netherlands, and more and more Yiddish-speakers ended up settling in Amsterdam, as much of post World War I Europe was in disarray.

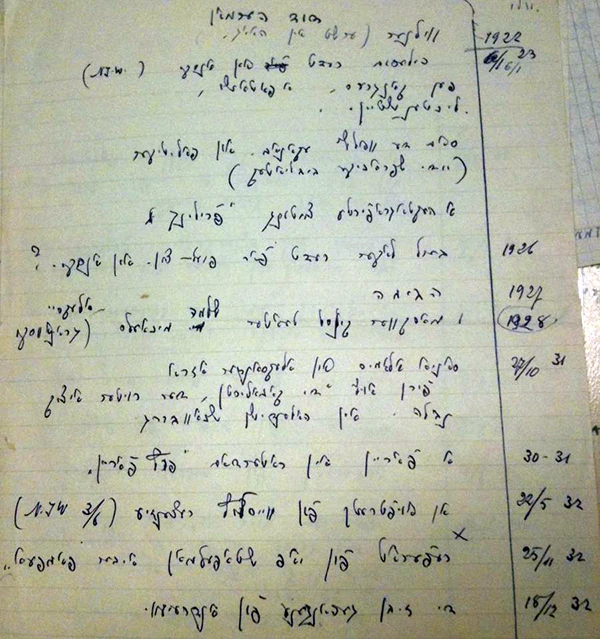

These new immigrants sought out a Jewish cultural environment that wasn’t to be found on the streets of Amsterdam. M. Levenzon and eight young Yiddish-speaking immigrants — seven men and one woman — wanted to build a community around culture rather than politics, in a country where formal political activity was illegal for non-citizens. In the summer of 1921, they established the Ansky Society. As its charter proclaimed, “this group exists beyond every political movement.” This may have been a purely practical tactic to retain members and maintain a big-tent Yiddish organization, given the small size of the Amsterdam Yiddish-speaking community. Nonetheless, it would prove an important philosophy as European politics became more polarized. (In the 1930s, the Society became one of the loudest Dutch voices protesting fascism and Nazism in the 1930s. After the November 9, 1938 pogrom just over the border in Germany, the Society organized support on behalf of German-Jewish refugees.) To launch the Ansky Society, the founders recognized the need to collaborate with locals, who might at the very least supply a place for the group to hold events. They approached a furniture-making syndicate’s sympathetic secretary, who offered space for the Society’s gatherings.

The organization’s own history describes the Ansky group as “a Jewish cultural island,” which shared Amsterdam’s cultural landscape with other linguistically-defined subcultures. These included Frisian cultural organizations (the most visible ethnic minority in the Netherlands) along with French-language cultural groups clustered around the Alliance Française and the Église Wallone. By the 1920s and 30s, the Yiddish culture that eastern European immigrants brought was their own, with no real connection to the Yiddish of Amsterdam’s early modern past.

Whenever interwar traveling Yiddish culture appeared publicly—whether in Berlin, Paris, London, or Amsterdam—its presence created a stir among local culture makers, both Jewish and not. Despite the fact that the productions themselves, as well as the framing language of the event, took place in Yiddish, Dutch Jews, as well as the non-Jewish Dutch intelligentsia, showed deep interest in much of what the Ansky Society brought to their city.

In the summer of 1922, less than one year after the Ansky Society’s founding, the Vilna Troupe brought fifteen actors on a tour of The Hague and Amsterdam. Anticipation was high when the Jüdisches Kunsttheater, the Berlin-based Vilna Troupe’s official name, came to the Netherlands for its inaugural tour of western Europe, which included England, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. It was the first time the theatre performed for audiences with no linguistic connection to Yiddish. The Vilna Troupe’s visual aspects—its lighting, costuming, and staging—along with the actors’ performances, had to supersede the dialogue. The Ansky Society’s own nascent Drama Troupe also participated in the Vilna Troupe’s show, a common practice when traveling Yiddish theatre came to town.

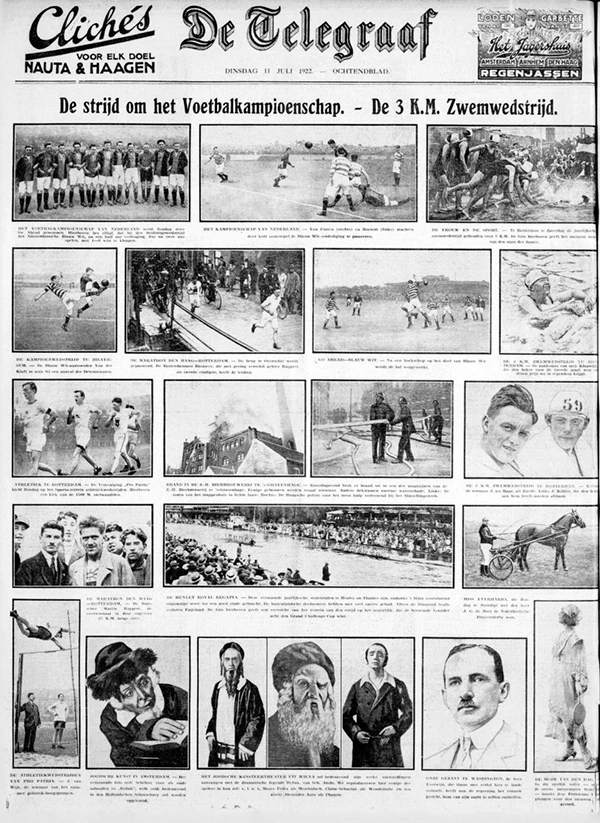

Although it put on eight different shows from its repertoire, including Dovid Pinski’s Yankl der shmid (Yankel the Blacksmith), it was the Troupe’s production of Der dibek (The Dybbuk) that became famous across Holland. In The Hague, An-sky’s play and the Vilna Troupe’s inspired production at the Princesse Schouwburg had a standing-room only crowd made up of Jews and non-Jews alike. That theatre—run by the German-Jewish theatre manager Hugo Helm, who had gained his experience in Berlin’s cabaret scene—was a film and playhouse that hosted many of The Hague’s cutting-edge productions. The run was so popular that the Troupe put on an extra show of Der dibek on a Monday, when the theatre would otherwise have been dark. Their productions in the Netherlands, which took place before the Troupe’s first venture to the United States in 1924, were covered by all of the major Dutch press. The 1922 visit was so financially successful that Helm brought the Vilna Troupe and Der dibek back one year later, this time for a three-city tour at the Koninklijke Schouwburg in The Hague, the Schouwburg in Rotterdam, and the Stadsschouwburg in Amsterdam, all central cultural venues. The Troupe’s success in the Netherlands should not have been a surprise to anyone familiar with its reputation in cities that had Yiddish-speaking communities. (It clearly wasn’t a surprise to Helm.)

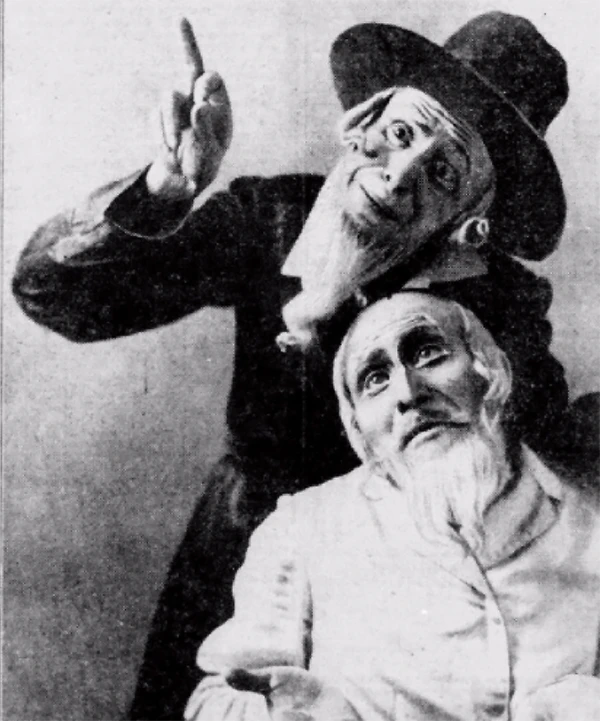

In 1927 and 1928, the Yiddish-speaking community pulled two cultural coups that brought them even more attention from Dutch society, both Jewish and not. Again under the auspices of Helm, the Moscow Hebrew-language Habima theatre, whose name was presented to Dutch readers as the Moskauer Hebräisches Künstlertheater HABIMA, included the Netherlands on its last European tour from Moscow before going into exile in British Mandate Palestine.

The Dutch press celebrated the visit and included photographs in the Algemeen Handelsblad and De Telegraaf of several characters who would appear in Habima’s signature production, which was also An-sky’s Der dibek. Since its productions were in Hebrew, there was little chance anyone in the audience would understand the dialogue. Therefore, to earn the acclaim it had already achieved beyond a tiny Hebrew-speaking audience, it relied on the theatricality of its presentation for which it was widely known.

Habima performed in Rotterdam, Utrecht, The Hague, and Amsterdam in November 1927 to admiring audiences, including Crown Princess Juliana, a royal appearance that made it into the Ansky Society’s spotty records of its 1920s highlights, as well as the pages of several newspapers.

A second Moscow-based Jewish theatre company toured the Netherlands in 1928. In late August, the Moscow State Jewish Theatre, GOSET, the Soviet Union’s state-sponsored Yiddish theatre, came to the Netherlands for the first time. A Yiddish theatre actor, Boris Abramov, coordinated GOSET’s visit to Belgium and the Netherlands. Abramov was originally from Bessarabia, but he had settled in Brussels and gotten involved in the theatre business in his new home. As Het Vaderland reported, those hosting GOSET managed to secure the Hollandsche Schouwburg, one of Amsterdam’s most important cultural venues, for its three-evening visit. Sholem Aleichem’s 200,000 opened on Thursday, Mendele Moykher Sforim’s Masoes Binyomin ha-shlishi (The Travels of Benjamin III) ran on Friday, and Avrom Goldfaden’s Kishefmakherin (The Witch) on Saturday.

The Yiddish-speaking immigrant community and its taste for modernist theatre made these traveling Yiddish and Hebrew theatre productions an institution among the modest Dutch intelligentsia; even Dutch royalty imbibed the Jewish culture of Communist Moscow. The Yiddish-speaking immigrant community did something that the native Dutch-Jewish community, deeply-rooted in Dutch culture, had not: they brought the cutting-edge art of a marginalized people, in a foreign language, from a politically suspect country to a relatively conservative Dutch society only gradually seeing itself as part of the larger world.

If there was one complaint about GOSET’s visit, it was not in the Communist orientation of the theatre or in the fact that their plays were in Yiddish. Because Abramov had organized GOSET’s tours to both Belgium and the Netherlands, he printed only one set of programs, in French (and presumably in Yiddish, although I did not have access to the theatre programs). As the reviewer for the social-democratic newspaper Het Volk wrote, “Only one request to the impresario who owns this tour — he should produce the program and explanation in the Dutch language. It is not only foolish, but also disrespectful to the majority of visitors to sell a program [in the Netherlands] in French.” The reviewer’s comment reminds us that Dutch audiences also wanted to be part of this global Yiddish theatre sensation.

A longer version of this essay appeared in East European Jewish Affairs, Volume 46, Issue 2 (2016). It is found here.

The records for the Ansky Society are held at the Joods Historisch Museum in Amsterdam.

Article Author(s)

David Shneer

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER

David Shneer is Louis P. Singer Endowed Chair in Jewish History, Professor of History and Jewish Studies, and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He is a Distinguished Lecturer for the Association for Jewish Studies and is co-editor in chief of East European Jewish Affairs. He blogs at the Radical Jewish Traveler.