When History Belonged to the Opera Writers

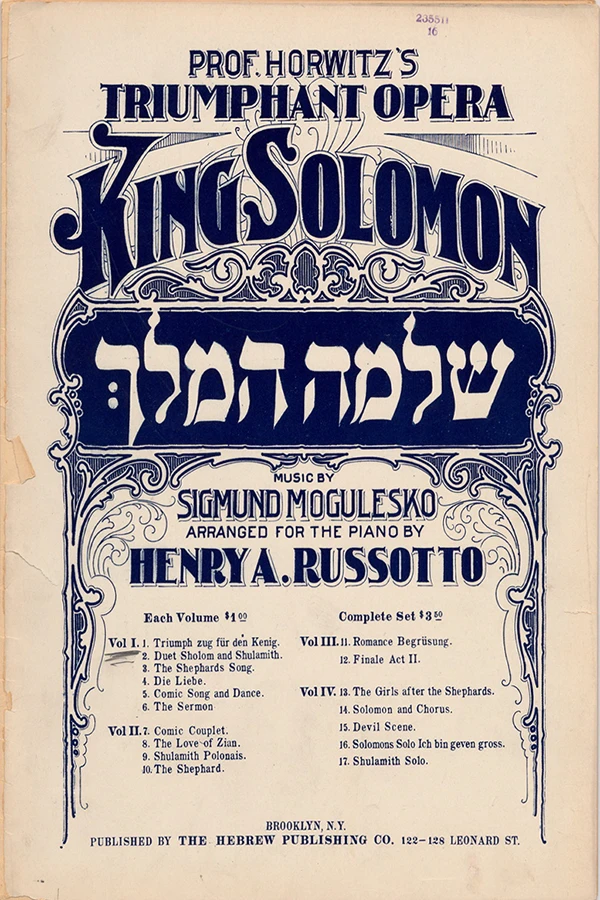

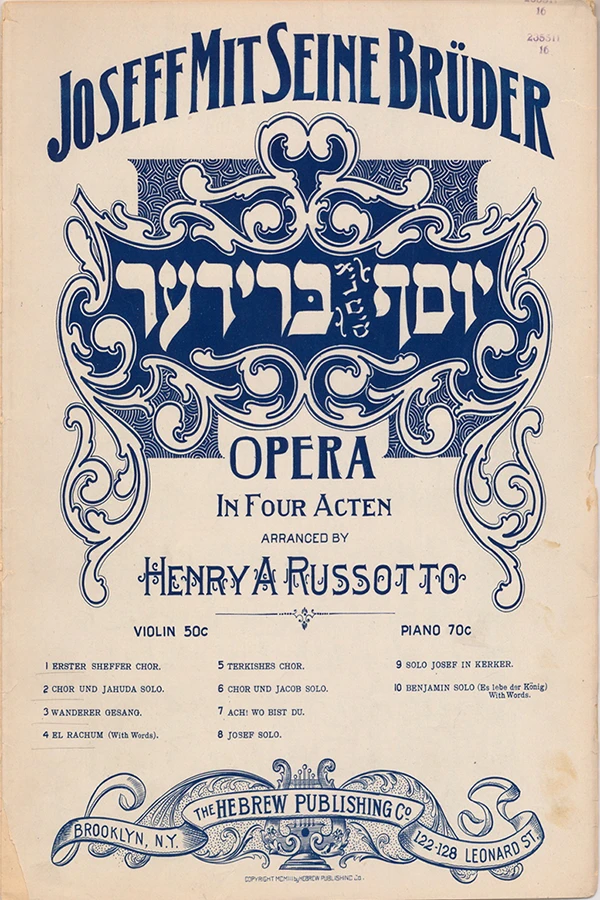

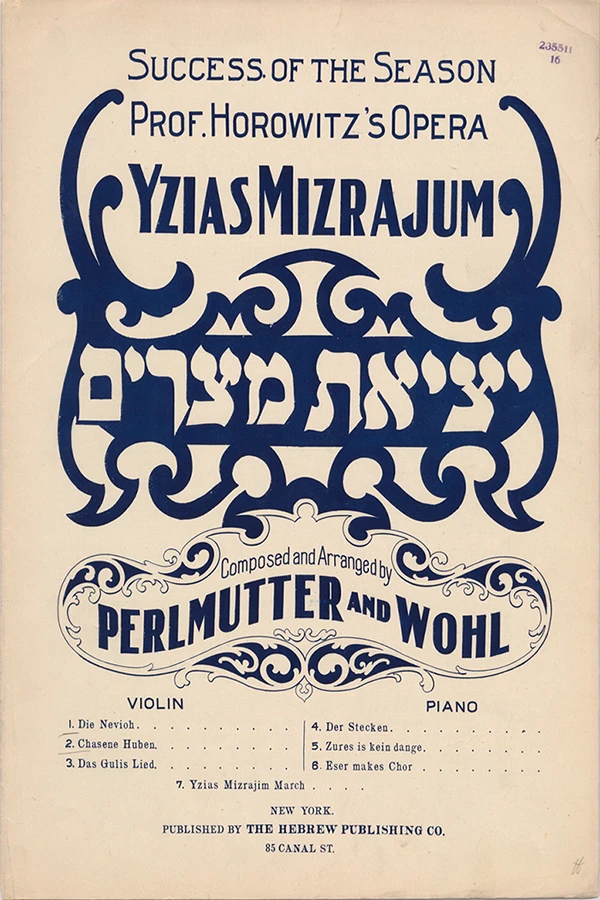

History belonged to the opera writers. First Goldfaden, and later Hurwitz and Lateiner and their followers, owned the franchise on Jewish history.

Zalmen Zylbercweig

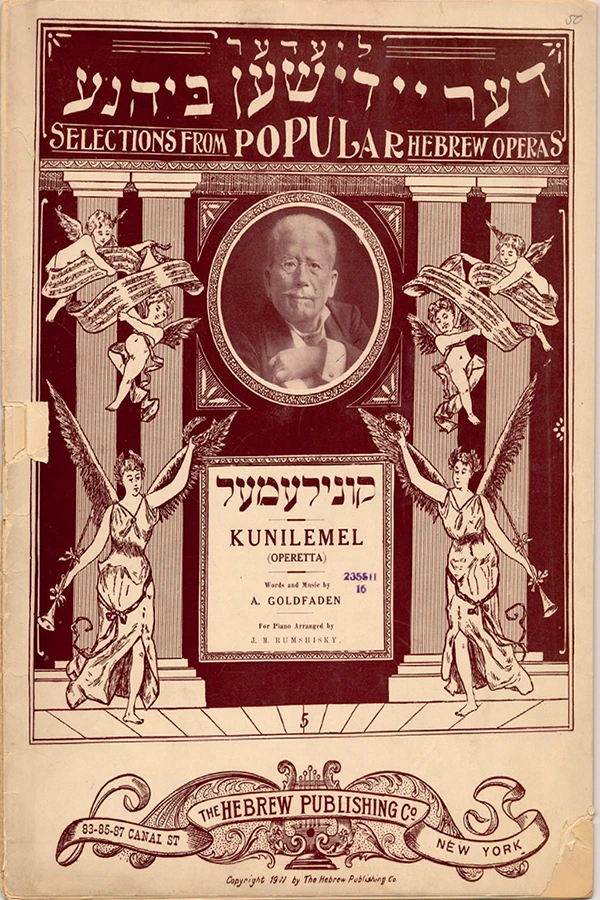

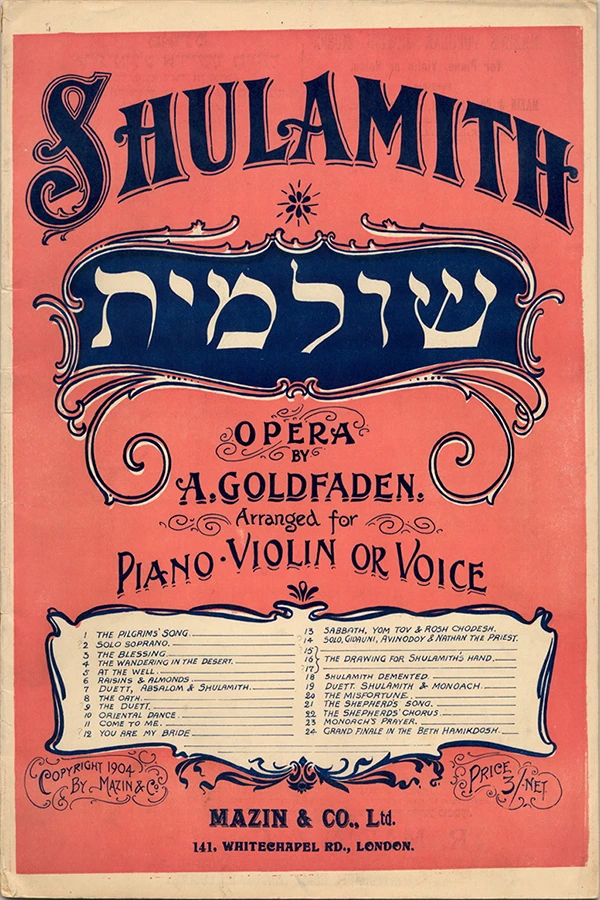

When Avrom Goldfaden dubbed himself the “Father of the Yiddish Stage,” the epithet was in many ways well-earned, if not exactly modest. His accomplishments as a manager, playwright, composer, and director are legion. But he was standing on the shoulders of others when he wrote some of his early hits, like the enormously popular but controversial farces Shmendrik (1877) and Der fanatik, oder di tsvey Kuni-Leml (The Fanatic, or the Two Kuni-Lemls, 1880), both of which sharply critiqued Hasidic beliefs and practices. So had a number of the first modern Yiddish plays, often written by maskilim (proponents of the Jewish Enlightenment, or Haskalah) as vehicles for an agenda that sought to balance traditional Jewish practice with modern learning and greater participation in secular society. While Goldfaden put his own unique stamp on this tradition, he was indeed working within it, rather than inventing something entirely new.

That tradition included no shortage of characters and scenarios whose crudeness opened the door for Goldfaden’s contemporary Yoysef Yude Lerner to take, in his view, a loftier path. This is how Lerner described the result, in his foreword to the 1903 edition of his brilliant, and highly influential, Yiddish translation of Karl Gutzkow’s classic German drama Karl Gutzkow’s classic German drama Uriel Acosta:

Smack in the middle of all the fuss that various “Shmendriks” and “Kuni-Lemls” were making several years ago in the little world of the Yiddish theatre … I decided to give it a try and wrote several historical plays. In those plays, noble heroes took the place of lunatics and cripples, and instead of dark, ugly scenes, one could see brilliant and ennobling images of the holy past. My hope that the simple people would find its way again did not deceive me, and with great joy I saw how warmly serious dramas were received … The Jewish stomach can also digest fresh dishes, as long as they’re prepared properly.

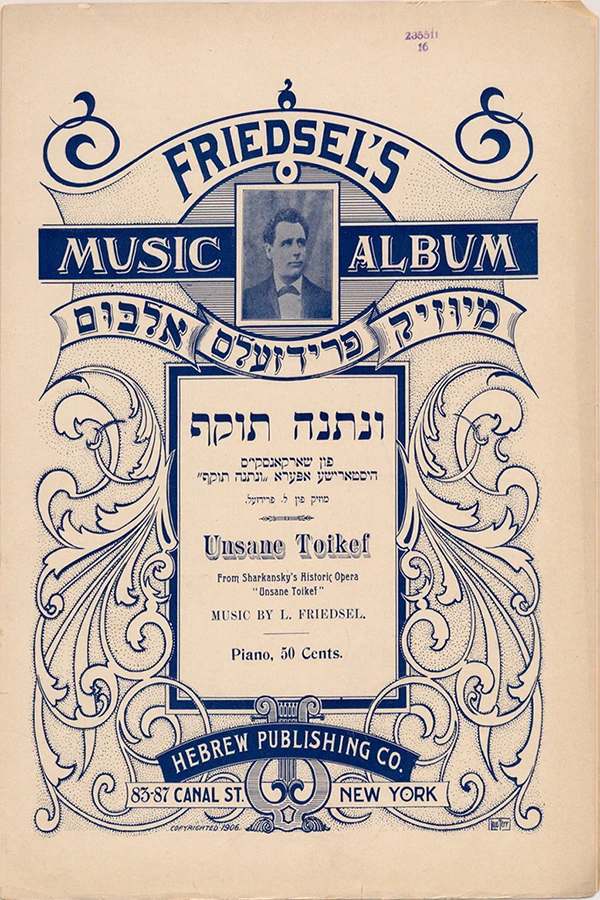

However self-serving this description was, Lerner was surely right that Yiddish audiences could handle both the high and the low; the fact that Uriel Acosta became a staple of the Yiddish repertoire was a case in point. Serious-minded dramas would co-exist on Yiddish stages with frivolous farces, highly sentimental melodramas, and musical confections. As for historical operas, a glimpse at productions on New York’s Yiddish stages from the 1880s to around World War I gives us a sense of trends in their texts, production, and reception.

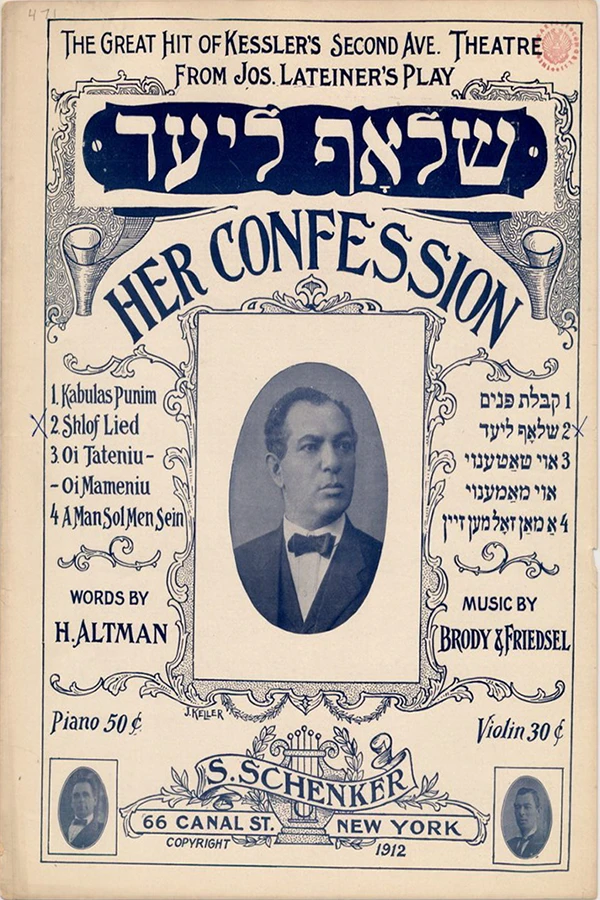

It is important to note, though, that some of these plays and performances met with high praise. A critic watching David Kessler play Judah Maccabee in that same year—possibly in the Lateiner version mentioned above, or possibly in a version of the story by a rival playwright—felt that the actor “does not act this role, but rather feels it with all his soul. He is the true Judah on the stage; his cries of anguish are so realistic that the spectator forgets the name Kessler; he cries real tears.” Similarly, one of Kessler’s most talented colleagues was praised for her portrayal of Deborah in 1890: “From the beginning to the end, Madame [Keni] Liptzin outdid herself. Every look, every gesture, and every cry were understood by the capacity audience. She created sympathy, horror, and pity with her acting. The whole time that Madame Liptzin was on stage, everyone in the audience sat as if smitten.” And music often enhanced the dramatic performances, as in an 1887 production of Moyshe Hurwitz’s Don Joseph Abravanel, a quasi-historical treatment of events relating to the Spanish Inquisition: “The Turkish-Arabic melodies that adorn this enjoyable production,” wrote a reviewer, “are sung by Madame Finkel with a tasteful timbre and with a moving, artistic softness that washes in metallic chords over the beautifully decorated stage.”

Historical operas, then, were capable of giving Yiddish audiences great pleasure. After all, if they hadn’t, the form would have fizzled out quickly. And sometimes they were considered too realistic. An anonymous letter to a New York Yiddish newspaper in 1885 found the closing scene of Goldfaden’s Bar Kokhba to be “too natural. The supernumeraries have poured their hearts and souls into the scene with such force that they beat each other as in a real war…. They should remember that their enemies on the stage are not real Romans, and there is no need for vengeance.” Could the writer have been in the theatre’s employ, and come up with a clever way to get some free, titillating advertising? Perhaps. Just as possible, though, this was a genuine response, a backhanded appreciation of the energy with which the performers threw themselves into their historical subject in these raw, early days of the American Yiddish stage.

Article Author(s)