The DYTP Remembers David Shneer

The DYTP mourns the untimely passing of our colleague and friend, David Shneer. On two occasions David contributed to the DYTP and his entries are found here and here. Below, members of DYTP’s research team and advisory board reflect on their encounters with David and his work.

Joel Berkowitz

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, DYTP Co-Founder

I first met David at a Yiddish Studies conference in Krakow in 1999. I remember being struck right away by how his broad smile seemed to arrive several moments before the rest of him did, and by his lively engagement with ideas. A notable moment at that conference came in the form of an animated exchange between David and an éminence grise among Soviet Jewish historians. While I didn’t know the subject matter well enough to evaluate it fully, it felt as if I was witnessing a snapshot of a paradigm shift in how Soviet Jewish culture was interpreted. And sure enough, David was in the process of becoming a leading voice among a new generation of scholars in that field, as other contributors to this post so vividly describe.

Fast forward a few years, and David and I would find ourselves in new jobs, directing and teaching in Jewish Studies programs. Though we lived and worked far from one another, we would cross paths in person on various occasions, leaving me with vivid memories of conversations over the years in conference-hotel hallways, during and between sessions at professional workshops, at annual breakfast meetings of the editorial board of East European Jewish Affairs, or over drinks at the bar at the end of long (but happy) days of delivering and listening to conference papers. Many of these were in the company of numerous mutual friends, like my fellow contributors here. All of them were enlivened by David’s relentless energy, inquisitiveness, warmth, and kindness.

Fast forward another decade or so, to 2013, when I finally found the perfect opportunity to bring David to my university in Milwaukee: to deliver a lecture marking the anniversary of Kristallnacht, and give some other more intimate presentations as well. I’ve hosted many remarkable speakers over the years, but David’s visit still stands out: among other reasons, because of his boundless energy, the ease with which he interacted with people, and his versatility as a scholar. In the course of a thirty-six-hour visit, David gave three public talks and also visited a class I was teaching and co-taught a session with me on Soviet Yiddish theatre and film. The class visit provided the double delight of watching clips featuring the great Soviet Yiddish actor Solomon Mikhoels, and having them put in context by one of the leading scholars of Soviet Jewish culture. My students participated with all the enthusiasm of Mikhoels’s character Nosn Beker doing his part to help turn the city of Magnitogorsk into a manufacturing hub.

In addition to his well-received Kristallnacht lecture, from material in his book Through Soviet Jewish Eyes, David gave two presentations in my campus’s Hillel building: a workshop related to his co-edited volume Torah Queeries, on LGBT perspectives on the Torah, and personal reflections on his work as a Jewish LGBT activist. Stories David told in the latter session resonated particularly strongly with a community member from an older generation, who responded with stories of his own engagement with the Jewish LGBT world over an even longer period of time. It was one of those moments one always wishes for, when the visiting lecturer not only makes a mark on the audience, but is in turn enriched by that interaction.

The Digital Yiddish Theatre Project mourns David’s premature passing and cherishes his memory. We feel fortunate that his prolific writing on Jewish cultural history twice found its way to the DYTP blog, in an article on a little-known Yiddish cultural society in Amsterdam, and a lively review, co-authored with fellow historian Rebecca Kobrin, of the Yiddish-language revival of Fiddler on the Roof. The reflections shared in this post illustrate just a few of the ways that David enriched the academic fields he worked in and the countless lives he touched. May his memory be a blessing.

Sonia Gollance

The Ohio State University, Managing Editor, Plotting Yiddish Drama

The first Yiddish book I ever purchased was a slim green volume, a Yiddish translation of Arthur Schnitzler’s provocative play Reigen (La Ronde). That was the summer I started studying Yiddish. I was a Steiner intern at the Yiddish Book Center, and I decided to show off my new treasure to the instructor for my Yiddish culture class. David Shneer was the perfect person to share in the giddy excitement of a new Yiddishist. He looked over the volume appreciatively, noting the translator’s rather fantastical name: D. B. Mikrokosmos. I pointed out how I had already deciphered some of the names of the characters, like “di prostitutke.” Yet I was confused about the title, Der karahod, which did not have a readily recognizable Germanic cognate. David said he thought it was a Ukrainian circle dance. At the time, I did not know that I would go on to write about dance or about the significance of the karahod as a structuring device in Yiddish literature. I later learned that the karahod is a Slavic circle dance more broadly, yet it took a while for me to stop thinking of it as Ukrainian. The truth, I realized, was that the beautiful memory of that conversation with David had imprinted itself on my mind.

I was nothing if not enthusiastic that summer, a twenty-year-old college student who knew I wanted to go to graduate school but did not yet know what that entailed. The Yiddish Book Center had assembled a great group of instructors, and I relished the opportunity to talk with them. David was particularly amenable to being peppered with questions. I remember being both intimidated and impressed by him, yet David was also approachable. I told him I wanted to live in Germany for a year after college and go on to pursue a PhD––and he weighed in on where I should go. As he held the copy of Der karahod that was newly mine, David explained that one day I could write an entire article about it. This was the first time someone had given me a sense of the possible scope for an academic article, and it blew my mind.

It did not occur to me at the time to be surprised that an established male academic would see a female undergraduate, at the height of her collegiate hippie phase, as a future scholar. Yet now I realize just how empowering my encounter with David was. He treated me as someone who might follow a path similar to his own, which helped broaden my ideas about what was possible and what questions to consider in pursuing the future I wanted. Yet that wasn’t all. The texts David taught in his class emphasized Yiddish culture as a scrappy underdog, voiced by women and working-class poets. From early on, I viewed the Yiddish canon as a dynamic space that could be contested and expanded. I felt my horizons were broad in terms of the research questions I could ask and what I could bring to the field through my scholarship. David deserves a lot of credit for the way he shaped my perspectives on Yiddish studies. May his memory be a blessing.

Nick Underwood

The College of Idaho, DYTP Project Manager

I visited Colorado for the first time in 2009 under the auspices of the Posen Foundation. At the time, I was the grants liaison for the Foundation’s New York-based Center for Cultural Judaism. I was visiting the University of Denver (DU) because it was a grant recipient for which David was the principal investigator. We spent two full days together. He had recently started his position at CU Boulder, but he maintained a connection to DU because of the grant. I had done many of these campus visits, but this one quite literally changed my personal and professional life. In the car, on the way back from Boulder to Denver and on the last day of my visit, I was telling David about how I wanted to go back to grad school (I had an MA in history at the time), and I shared with him some of what I was interested in. Then, I really wanted to work on something related to Yiddish culture, the Spanish Civil War, and France. David turned to me and asked, “where are you applying?” I named a few programs, and he said, “Add CU to the list. We will be adding a German historian in the next year or two and we are expanding Jewish studies. You should think about it.” I appreciated the invitation, and I got the feeling that we might work well together, something that was important to me. So, I applied; I got in. And my family moved to Colorado.

I was inspired by David’s scholarship, his program-building, and his way with people. He was who I wanted to be as an academic. I admired (and still do) his way of analyzing culture and also taking seriously the ways that performance helps build community. He analyzed European Jewish culture in a way that took seriously culture makers’ and cultural activists’ current moment, eschewing foreshadowing. I would eventually take the approach he developed in Yiddish and the Creation of Soviet Jewish Culture: 1918-1930 and apply it to interwar France. It led me to ask: so what that the fall of the Third French Republic and Vichy years were on the horizon in 1930s France? That doesn’t diminish the real attempt at French belonging that immigrant Jews in France attempted. David was instrumental in pushing me to see the 1920s and 1930s in this way. As we worked together, his work on performance and visual culture also fundamentally shaped the way I used sources and incorporated them into my narratives. He is very present in how I think and write.

David blended his research into his programmatic and public work remarkably seamlessly. When I came to CU, I brought with me an administrative background. I like admin—(I know, I know!)—and he guided me here, too. He was very deliberate in how he structured programs, but he was also open to hearing everyone’s voices and contributions. He made people feel heard. He shaped things, but also gave people the freedom to feel a sense of ownership over their contributions and the final product. He took students’ (undergraduate and graduate) voices seriously, and he built bridges in meaningful ways.

David was seemingly involved in everything, and he encouraged me to do the same. Together we built aspects of the graduate program in Jewish studies at CU, we worked with Anna Shternshis as part of the editorial team of East European Jewish Affairs for almost six years, and we collaborated on conference panels. Recently, we had been working as guest editors of what would have been our last issue of EEJA––its forthcoming fiftieth-anniversary issue. Together, we finished editing the essays for the issue in the week before he died. We were also planning on write something together. He was so very good at co-authorship. He also recently helped me think through the redevelopment of the Judaic studies minor at The College of Idaho. I wanted to globalize the curriculum in a way that emulated our approach at CU. He said “yes” to a lot of things and always had time for people. He was revolutionary in this thinking and program-building and he was, quite simply, a joy to be around.

One of the many things I’ll miss is an odd tradition we started at some point when I was off doing archival work. Whenever I would finish a day of research, I’d send him a text message of me drinking a glass of wine or a Belgian beer. The chalice was an important part of the image. He would then remind me that, actually experiencing the places you were researching, was also—one might say the most important—part of research. That is, research is not only about archival findings. This summed him up. He was that rare perfect blend of mentor, colleague, and friend. He challenged you to do more, he supported you in doing whatever it was, and he encouraged you to have fun while doing it.

Michael Berkowitz

University College London, DYTP Advisory Board

It is truly an honor to contribute to this memorial and remembrance of our beloved David Shneer (z”l).

In terms of quality, heft, and impact on the field, David’s scholarship did more to bridge the traditional disciplinary boundaries, and to enhance modern Jewish history from the perspective of interdisciplinarity, than that of any other historian of Jewish Studies of his generation. I do not say this lightly. In total, his thoughtful, creative, historically-grounded integration of literature, photography, gender, and music, is unsurpassed.

I strongly believe that despite numerous awards and various accolades, David’s achievements were not recognized to the extent that they deserved. Jewish Studies, overall, is a conservative field that has doggedly resisted the innovations that David championed. (I will never forget what a struggle it was to convince the Association for Jewish Studies that it should allow the use of a slide projector in a conference session in the early 1990s.)

I initially read David’s two major monographs soon after their publication. I was impressed at the time, and my esteem for his work only grew over the years. As I myself continue in the field of Jews and photography, I repeatedly turn to David’s work—and appreciate it all the more. His book on Yiddish in the Soviet Union not only holds up well; it has helped shape an entire field.

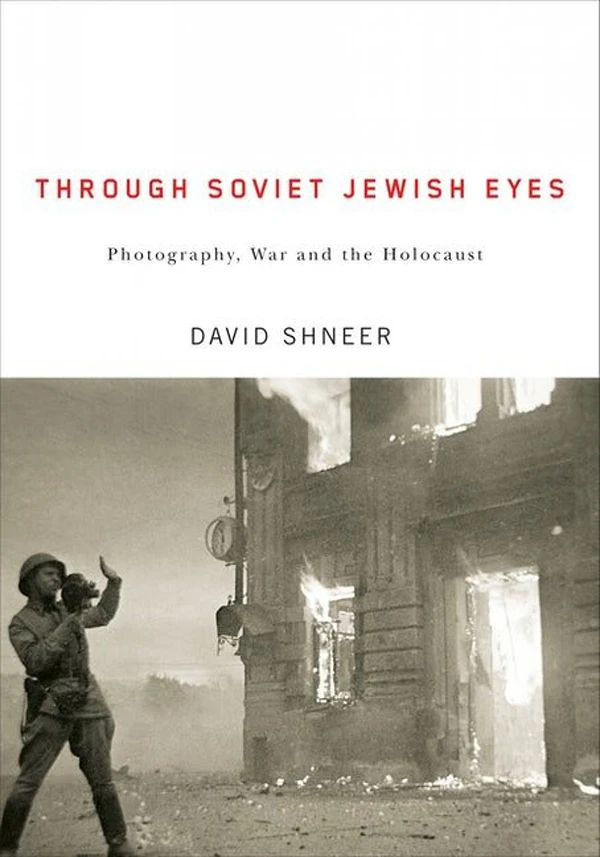

While on sabbatical, based in Washington and New York during academic year 2016-17, when giving presentations about my current research on filmmaking in the United States during the Second World War, I prominently mentioned David’s book on Soviet Jewish photojournalists. This was not simply a polite or passing reference to the historiography. I emphasized that my findings about Jews working for the US Army Signal Corps, as photographers and cinematographers, bore striking similarities to David’s interpretation of their Soviet counterparts. There is no single work that has been more important to the foregrounding of my project than Through Soviet Jewish Eyes.

David was highly prolific. He wrote dozens of articles and book chapters, many of which are entirely separate from his monographs and edited books. He edited significant and fascinating anthologies that have truly advanced the fields of history and Jewish Studies.

His book based on his Berkeley PhD dissertation, Yiddish and the Creation of Soviet Jewish Culture, 1918-1939 attained the status of a classic after only a few years. For the most part, the subject he considered had been seen as something of a prelude to the demolition of Jewish collective identity—and outright state murder—in the USSR. In resisting the urge to “backshadow,” he developed a persuasive case for the complex, substantive, and symbolic role of Yiddish within official Soviet and Soviet Jewish culture. He not only corrected the historical record but filled a crucial lacuna within modern Jewish history. I think it is one of the best five or six books, in all of modern Jewish history, written in the last twenty years. It revealed a depth and breadth of analysis that one might expect from a scholar who had spent decades on the subject. The fact that such a mature, reasoned, well-written, and provocative book emerged in such short order from his PhD was, in a word, incredible. Moreover, this book demonstrated a superb historical imagination and intellectual courage. David’s illumination of “the politics of language and culture”—such as the suppression of Hebrew, and “conflict” between Yiddish and Hebrew—resulted in one the finest interpretations of Jewish modernity, ever.

I can speak of his book Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War, and the Holocaust with even greater exuberance. David was the first scholar of Jewish Studies to recognize the extent to which photography was a “Jewish” field in Eastern Europe. This work, therefore, is not only a tremendous contribution to the field of cultural studies, but addresses critical issues pertaining to Jewish social history, and European history generally, that few other scholars had even touched. He proved himself to be exceptional in reading images, and without equal in exploring the complex world behind the photographs. This book had a tremendous and still growing reception. It represents a level of sophistication in dealing with visual culture, in Jewish Studies, that broke the mold.

David’s later work included a study of a Dutch-Jewish Yiddish-language cabaret actress, Lin Jaldati, and her daughter, Jaida Rebling. The project was extremely significant from a number of perspectives. Obviously the Holocaust decimated European Jewry. But the presence and roles of Jews in post-Second World War Europe remains a critical topic. David uncovered the career of a woman who created an unprecedented role for herself as a bridge between eras and cultures. David showed, yet again, that he was in a class of his own as an interlocutor between Yiddish-speaking, pre-1939 Europe, the Holocaust, and the postwar period. He also was remarkable for his success in reconstructing and analyzing Jewish popular culture that was, in some respects, far more important for understanding the lives of Jews than traditional approaches that privilege the lenses of (narrowly defined) religion and politics.

David was an industrious, prolific historian, whose work was extraordinarily creative. By all measures he was a constructive, imaginative, active force and an outstanding citizen of his diverse academic homes. He produced work of the utmost originality and quality that will prove of enduring significance. David had, in the best sense, a live mind, and the legacies of his scholarship will no doubt continue to shape and stimulate historical questions and thereby attain increasing eminence.

Jeffrey Veidlinger

University of Michigan, DYTP Advisory Board

For much of the twentieth century, most scholarship in Jewish history focused on the Jews of Central Europe and Germany. This was particularly evident in the fields of cultural and intellectual history, where Soviet Yiddish writers, Russian Jewish philosophers, Ukrainian Jewish artists, and Romanian Jewish musicians were routinely ignored in favor of their more famous German counterparts. Much of this neglect could be attributed to Cold War politics, which both demeaned Soviet cultural activity and made it difficult to gain access to the cultural achievements of the Soviet Union. The recognition that there had been a lively Yiddish culture in the Soviet Union also threatened to undermine the portrayal of the Communist state as universally anti-Semitic. The anti-Zionist message of much of Soviet Jewish culture also posed problems for many in the west.

David Shneer was among the first cadre of graduate students to mine Soviet archives and, like many of his cohort, came to realize the riches of Soviet Yiddish culture and Jewish cultural achievement in the Soviet Union. In his first book, Yiddish and the Creation of Soviet Jewish Culture, David showed how Yiddish cultural activists in the prewar Soviet Union developed an extensive publishing industry of books and periodicals, and a vibrant network of poets, writers, and literary critics. He argued that Soviet Jewish writers and activists were able to maintain a multivocality that allowed them to be both Soviet and Jewish simultaneously––”Soviet and kosher,” as Anna Shternshis would later put it. Since then, this viewpoint has become the standard narrative, and Shneer’s first book has become a seminal volume.

David’s second monographic study of Soviet Jewry was, I believe, even more remarkable. Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War, and the Holocaust, which traces the development of Soviet photojournalism from its earliest days to the postwar period, points to the large number of Jews who became photojournalists and to the multiple complexities their identities played in their work. In the pre-war period, for instance, David shows how they celebrated the achievements of Communist construction while avoiding the terrible price that much of the Soviet population paid for that construction. But the story becomes truly extraordinary during the war, when David’s photojournalistic subjects confront the casualties of Nazi atrocities. The Soviet Jewish photojournalists who reached Kerch after its liberation from the Germans became the first journalists anywhere to document the Holocaust. With this realization, Shneer completely transforms our understanding of the way that news of the Holocaust spread, making a significant contribution not only to Soviet history but also to Holocaust Studies.

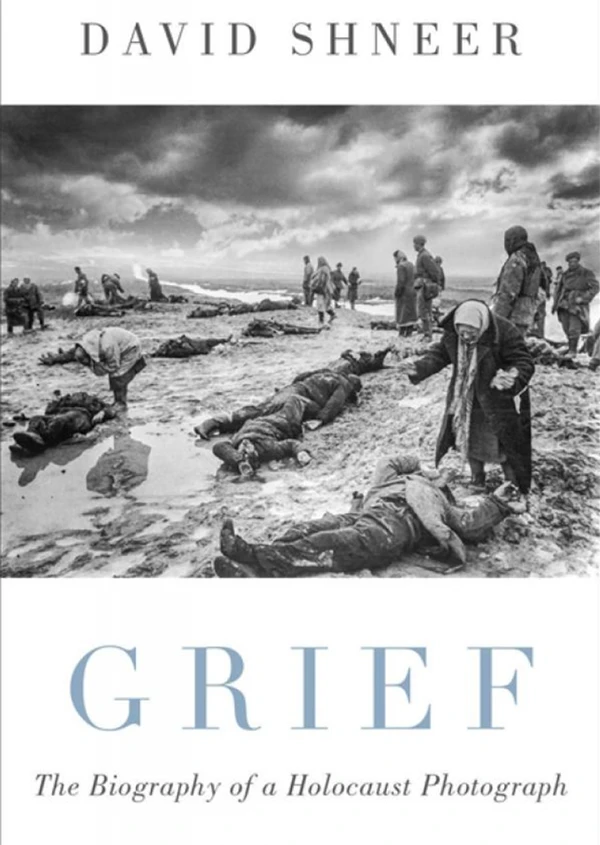

Whereas the Soviet government had always been condemned for covering up the Holocaust, Shneer shows that the Soviet press was, in fact, the first to document it in all its horrors. Not only were the first images of mass graves near Kerch widely broadcast and distributed to the world, but Soviet photos of the liberation of Majdanek provided the first photo documentation of the extermination camps. David’s analysis of different versions of the same photo demonstrates how Soviet and Jewish memory and identity intersected with each other in disparate ways. In his final book, Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph, David returned to one haunting photo that Dmitri Baltermants took of an anti-tank ditch near Kerch, forcing us to ask difficult questions about the Jewish particularities of the Holocaust, the Holocaust in the Soviet context, the role of photography, and the meaning of grief itself.

As those of us who had the privilege of knowing David deal with our own grief in confronting the loss of a vibrant, engaging, and generous mentsh, his oeuvre stands as a testament to his lasting scholarly legacy.

Article Author(s)

Joel Berkowitz

Joel is Professor of English and Director of the Sam and Helen Stahl Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Sonia Gollance

Sonia Gollance is Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Yiddish at University College London.

Nick Underwood

Nick Underwood is assistant professor of history and the Berger-Neilsen Chair of Judaic Studies at The College of Idaho.

Michael Berkowitz

Michael Berkowitz is professor of Modern Jewish history at University College London