Osherowitch and Rumshinsky on the Piety of Regina Prager

Translated by Beth Dwoskin, with introductory notes by Beth Dwoskin, Alyssa Quint, and Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel

Regina Prager was one of the first leading ladies of the Yiddish stage, known for her extraordinary operatic voice and her continued Jewish observance throughout her life. Born in Lemberg, Galicia (then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today Lviv, Ukraine), in 1866, Prager was the proper and pious doyenne to her friend and sometime-rival, the Yiddish actress Bertha Kalich (1874-1939). Both were born in Lemberg, both had formal vocal training, and they performed together, first in the chorus of Skarbek’s Polish theatre (ca. 1887-8) and then in Yankev Ber Gimpel’s Yiddish theatre. Both emigrated to the United States. Prager’s religious temperament, her modest demeanor, and her matronly appearance all worked against her desire to become a romantic leading lady. With her voice, however, she soared. Indeed, her fame stemmed almost entirely from the quality of her singing.

The following two extracts are from a tribute to Prager by the journalist and frequent biographer of Yiddish actors, M. Osherowitch (1885-1965) and an excerpt from Joseph Rumshinsky’s 1944 autobiography, Klangen fun mayn lebn. Osherowitch describes how Prager distanced herself from what she saw as the superficial interests of her theatre colleagues and continued to lead a traditional religious life. Both Osherovitch and Rumshinsky glorify Prager’s insistence on her continued Jewish observance. Osherowitch also writes thoughtfully of her transition from youthful to older roles, reflecting how actresses, then and now, face expectations about age and gender on the stage. Osherowitch’s remarks on Prager’s youth, beauty, modesty, and religious observance are informed by his strong male gaze. But his discussion is not without insights. Absent any record of Prager’s life in her own voice, Osherowitch provides information on Prager’s success as well as how she negotiated her private religious life and her public theatrical life. A second account by the composer Joseph Rumshinsky describes how he and Boris Thomashefsky came to create a role for Prager in Di Khaznte, their Yiddish adaptation of a popular anti-Semitic farce by Carl Roessler entitled Die finf Frankfurter (The Five Frankfurters), about the famous banking family. Rumshinsky and Thomashefsky substituted the German original’s banking family—led by a widow with five financier sons—for a cantor’s widow with five sons who are successful artists and impresarios. This role ushered in a new era of singing mother roles on the Yiddish stage. In the eyes of Osherowitch and Rumshinsky, Prager embodied the ideal Jewish woman: observant of Jewish law, modest in demeanor, and naturally inclined to motherhood.

“Regina Prager, the Famous Singer of the Yiddish Stage, Talks about her Theatre Life”1 More than 30 years on the Yiddish Stage – Her Beginnings in Lemberg – Her Experiences and Acquaintances

By M. (Mendl) Osherowitch, Forverts

The name “Madame Regina Prager” is tightly bound with the story of Yiddish theatre.

When a listener hears her sing in an operetta that is polished and produced in the Broadway style, he is immediately struck by the authentic Yiddish tone, the sweet and pleasant sound of the bygone historical operettas that Abraham Goldfaden wrote. And it seems as though suddenly a miracle has occurred, and out of the blue, he is hearing “the reincarnation of a melody,” so that the sounds and notes of the present day mix with the old Yiddish melody from the past, and together they blaze a wide path into his heart and he feels the old song:

“Oy, cry, everyone,

Daughters of Zion

Mourn, all you children,

side by side.”

Such is the impression made by Madame Regina Prager. On stage, she carries within herself one of the most beautiful chapters in the history of Yiddish theatre; and it sings forth from her with the same youthful freshness as in the past.

It has already been more than thirty years since Madame Prager began performing in the Yiddish theatre. During that time, Yiddish theatre, especially in America, changed considerably; many conventions were abandoned, influenced by various new winds that blew from every direction. Together with the change in Yiddish theatre, many performers changed in order to adapt to the spirit of the times, and one of the only ones who didn’t change and remained firm in the struggle is Madame Prager.

In our day, she still remains not only the actress who performed in Yiddish, but the only Jewish actress.

Indeed, for this reason, she feels strange in the new atmosphere of the Yiddish theatre …

“Once”, she said this to me, nodding her head piously, after a performance of Der kleyner mazik (The Little Rascal), where she played together with Molly Picon, “Once people felt at home on the Yiddish stage; wherever you looked, you saw Jews with long beards and long coats, women with wigs and silk scarves, Jewish daughters with long dresses and modestly downcast eyes. You also saw a Sefer Torah. People made Kiddush. They sang Sabbath songs and also “God full of Mercy” was not missing. But now it’s completely different; no more Jews with beards and long coats; and as for women on the stage, it’s already been said—a chorus of young girls with short dresses and they kick their feet so high that it’s really frightening …”

It’s perhaps strange that a woman who has been an actress for some thirty years already should speak thus about Jewish piety. But when you are more familiar with the life and character of Madame Prager, it will not seem so strange. She is pious on the stage, just as she is pious in her life.

Piety absorbed her from childhood on. She was born in Lemberg, and her father was a very pious and honest Jew, and he brought up his children with a strong religious spirit.

He always said that a man should not wait for the chance to do a mitsve, a good deed, but rather that he should just look for the opportunity. He also used to say, that for that reason, a Jew who neglected his piety due to circumstances had not earned the right to be called a Jew, because God, alone, outlined the difficult task for his people so they may withstand the greatest trials, and thus remain honest Jews.

At home, an atmosphere of faith and religion always reigned, and in such an atmosphere Regina Prager passed the first years of her childhood, and this left deep traces that are still with her today …

When Regina Prager was still a little girl, she lost her mother in a frightful accident that still comes to life before her eyes. Friday night, when everyone in her house was asleep, the kerosene lamp flickered on the table, because that evening they couldn’t find the “Sabbath gentile” who would extinguish the lamp before they went to sleep. Either a wind blew from somewhere, or a cat jumped from somewhere. The lamp turned over, the Sabbath tablecloth caught fire, and soon the whole house was in flames.

When people in the house awoke from sleep in fear, a thick smoke surrounded them on all sides. There was a panic; everyone from all sides cried desperately. People were lost and didn’t know what to do first—rescue themselves, or rescue others. Children cried and grown people ran confused from one corner to another.

Regina was sleeping with her mother in the same bed that night, and it happened that she was rescued from the fire but her mother was burned to death. Speaking to me about that terrible event, Madame Prager cried. “I was just a little girl then,” she said. “No photograph remains of my mother, and today I don’t know what my mother looked like, what sort of face she had. As if in sleep, I remember only how she blessed the candles; afterwards I used to imitate her and then I would cry; and then my father used to say that I looked just like Mama, exactly. And until now, when I sit by myself in my dressing room and put on my makeup, looking in the mirror, I’m often pensive and a memory comes to me:

‘This is certainly just how my mother looked.’”

After her mother’s death, little Regina was sent away to a family of friends in a village near Lemberg. There, in the freedom of nature, among mountains and valleys and green trees, in her childish mind, slowly, over the course of years, the impression of that dreadful night weakened. She began to make friends with the peasant girls who were her age and since they knew many songs that people were in the habit of singing when they worked in the fields, she learned the songs and began to sing them.

But she wove a Jewish sadness into the “gentile songs,” a Jewish anguish; she instilled in them the Jewish piety that she absorbed from her father in her home.

For her, singing became not only an expression of joy, but also an expression of sadness, of grief, and of longing. In song, she expressed all her voices. She sang while playing with her friends in the garden. She sang when she stood alone on a mountain and watched the sun set. She sang while sitting alone in a valley, watching the play of the shadows on the green grass.

Always, she sang.

And always with sadness, always with woe; the sadness of a Jewish child, who is left without a mother, the woe of a young girl, who longs for something and knows perhaps not where and for whom …

And thus, the deep sadness that is genuine Jewishness remains in her singing to this day, even in an operetta that is modern, and decked out and garnished with all the tinsel of Broadway. When Prager comes out on the stage, it is as though a Jewish mother appeared. When she begins to sing, the heart of the spectator warms to her authentic Jewish tone, to her truly Jewish singing. And I was not surprised when Joseph Rumshinsky told me that when he conducts for Madame Regina Prager, when she stands on the stage and sings, he feels more than any other time, that he is conducting in a Jewish theatre …

The years passed. Regina Prager grew up, and then she began to search for a means to make a living …

People told her that with the voice she had she could achieve a great deal and reach great heights, and so Regina Prager began to dream about a career as an opera singer.

Regina Prager was by nature a very modest girl, which often caused her to be doubtful about her own ability, her own talent. She believed that she ought not to undertake too great a challenge and that she must not reach too high. In that respect, one can say that she is not an actress … quite often, she underestimated herself and she hated to talk about herself.

And I must say that it was very difficult for me to get her to reveal the facts about her life history …

“But it’s not interesting”, she would say to me, with genuine modesty. “What can I tell you? I was born in Lemberg, I had sorrow; I began to act in the Yiddish theatre about thirty years ago—and I am still performing today. That is all.”

This is not at all the story of a typical actress, who is accustomed to considering everything as a major, important news item, each trifling matter in her life, and to see in it a means for advertisement, for “publicity.”

And I must confess, that not even the old Madame Lovits, the mother of the Yiddish actress Pepi Lovits—a woman who was connected to Yiddish theatre for many long years and who remembers off the top of her head a great number of interesting things about the beginning of Yiddish theatre in Galicia and America—that it was only after some difficulty that could I obtain from her the facts about Madame Prager’s life story and about how she came to the Yiddish and stage and what sort of experiences she had as a Yiddish actress.

She, the old Madame Lovits, gave me considerable assistance.

The modesty, the reserve, which is, by the way, a very beautiful and sympathetic trait, was no small hindrance to Madame Regina Prager in the beginning of her career. When people said to her that with such a voice as she possessed she could reach great heights, she silently, in her heart, did indeed dream about a career as an opera singer. But at the same time, she had doubts about it …

“How can I rise to such heights?!” she thought.

In order to earn a little money and have the possibility of making a living for herself, she joined the chorus of a Polish theatre, where they staged Polish operettas and also operas. This offered her the possibility of becoming a self-supporting person, and then she began to study music. She took classes with a well-known voice teacher in Lemberg. He was very enthusiastic about her voice, and he was sure that Regina Prager would in time be a great singer.

In the Polish theatre, in the chorus, Regina Prager kept herself aloof from everyone, just as she does now. She did not mix her private life with her life on stage. She always remained a pious Yiddish daughter; after the performances, she did not connect with the other girls in the chorus, especially not with those who were a little inclined to frivolity. She was not interested in the love lives they were leading and she did not care about the young men who gathered around them.

Devoted and committed to her work, she was a choral singer on the stage, and at home a quiet, shy, modest Jewish daughter who feared God and obeyed His commandments.

But as often happens, quiet and shy girls are more popular with young men. [A]t that time, a very nice and sympathetic young man fell in love with Regina Prager; actually, the same musician from whom Regina Prager had taken singing lessons.

But Regina Prager herself knew nothing about it … moreover, she was so reserved and modest and withdrawn, that the other lacked courage to say how much he loved her. And for a long time, he struggled with himself, until he decided to end his life and shot himself … so say the old theatre people who remember Regina Prager from many years ago, when she was a young, beautiful girl and sang in the choir in a Polish theatre in Lemberg.

At that time—this was approximately in the year 1888—traveling Yiddish troupes that gave incidental performances here and there used to come to Lemberg.

These Yiddish troupes never lacked in hardship. They dragged themselves from Russia to Romania, and from Romania to Galicia; and in Galicia, without a special permit (concession) no Yiddish troupe was allowed to perform. Then, a well-known man, Mr. M. Volgeshafen,2 a retired soldier, obtained a permit, assembled a Yiddish troupe, and, with it, traveled to various cities and small towns in Galicia. The troupe was composed of Shmuel Lukatsher,3 Meyerovitsh, Madame Meyerovitsh, Miss Liza Einhorn (b. 1865, now the wife of the movie-director Ivan Abramson ( 1869-1934), Sam Adler4 and others.

Besides Volgeshafen’s troupe, Kalman Yuvelir5 also had a Yiddish troupe that traveled around Galicia and Romania.

In Lemberg itself, there was no Yiddish theatre. The first to bring a Yiddish theatre to Lemberg was a man by the name of Yankev Ber Gimpel (1840-1906).

Gimpel was a man with experience on stage. For forty years’ time he was in the chorus on the Polish stage, and when he founded the first permanent Yiddish theatre in Lemberg he gave it the name, “Jewish Polish Theatre.”

But a protest from the police forced him to change the name; and in the end, Gimpel’s theatre would be called only “Jewish Theatre.”

Gimpel’s troupe was at that time composed of actors who later became famous on the Yiddish stage: Berl Bernshteyn6 (the comic who died in America some years ago), Tabatshnikov,7 Peter Graf,8 Fishkind, and others. It was a great success for the troupe to have Tabatshnikov (Tobias). In the history of the Yiddish theatre it is written that at that time he was “taking Lemberg by storm.”

Two years later, that is to say, approximately in the year 1890, Regina Prager was also in Gimpel’s troupe.

She was there together with Bertha Kalich,9 who was at that time just a young girl. And she also brought along her brother-in-law. Regina Prager’s brother-in-law was a great lover of Yiddish theatre. He almost never missed a performance, and as he had a very high opinion of his sister-in-law Regina Prager, he was certain that she, with her beautiful voice, would be a big hit on the Yiddish stage and he began to persuade her that she should become a Yiddish actress and he prevailed. Regina Prager gave up the Polish stage and joined Yankev Ber Gimpel’s troupe.

There, her Yiddish singing found itself at home. She felt herself to be among her own people, in a familiar atmosphere, and the sad tones of her Yiddish song found a resonance in the hearts of thousands of her own people, who longed for them.

And then, Regina Prager experienced both fear and joy, which people normally undergo when they get a role for the first time. Her experience might have been stronger than it was for others because the first role that she got on the Yiddish stage reminded her of that fearful night when she lost her mother.

The first role Regina Prager performed on the Yiddish stage, in Gimpel’s theatre in Lemberg, was in the play Shloyme ha-meylekh (Solomon the King), which at that time was a great success. Regina Prager was then just a young girl, and in the role that they gave her to play, she had to be a mother—one of two mothers that came to Solomon the king, so that he could decide who was the true mother of a living child.

The word “mother” alone was for Regina Prager enough to call forth a stream of feelings in her heart. It reminded her immediately of the frightful night when her mother was burned to death. For her it evoked a feeling of longing for a mother, a feeling that was always near in the deepest depths of her soul.

Because she, the solitary girl without a mother, had to be a mother on the stage, the role became familiar, her own, close to her heart. And since she was, in accordance with her role, the true mother of the living child, she began to cry when the clever king gave forth the decree, that they should cut the living child in two; she played the role so naturally and passionately that she had everyone in tears. She particularly excelled at the tearful song that she sang after the king gave the order that the living child should be cut in two.

She was strongly inclined towards singing roles; they felt more comfortable to her than dramatic roles; but at that time, together with Regina Prager, Gimpel’s theatre also employed Bertha Kalich, who later became as famous a dramatic actress on the Yiddish as on the English stage in America. By chance, fate determined that for Gimpel in his theatre in Lemberg, Kalich was to be a prima donna and Prager—a dramatic actress.

That was how Gimpel managed his theatre at that time.

While she was performing on the Yiddish stage, Regina Prager continued to study music and still dreamed of a career as a singer in opera. Several rich people were interested in her and they were ready to give her the possibility to study further. And it may be that Regina Prager, who to this day possesses a type of quiet stubbornness in her character, could indeed have reached her goal and in time could have become a singer somewhere in a Polish opera.

But just at that time Avrom Goldfaden, the father of Yiddish theatre, came to Galicia after his first visit to America. Goldfaden came to Gimpel’s theatre where, in the course of a brief period, he prepared the performance of his new plays—Meshiekhs tsaytn (Time of the Messiah), Rabbi Yozelman, Akeydes Yitskhok (The Binding of Isaac), Loy sakhmoyd (Dos tsente gebot), (Thou Shalt Not Covet [The Tenth Commandment]), and others. He thought very highly of Regina Prager and when he heard that she wanted to leave the Yiddish theatre, he nearly assailed her:

“What do you mean, you want to leave the Yiddish stage?” he scolded. “After all, you were created to become a Jewish actress! A Jew and not a gentile! With them, with the gentiles, you will often have to play certain roles where you will have to make the sign of the cross … do you hear? Make the sign of the cross!” This made a strong impression on Regina Prager, and she gave up her idea of a career as a Polish opera singer …

In America, the field of Yiddish theatre was already substantially plowed. The pioneers of the Yiddish stage, the actors who came here from Russia and from Romania and from Galicia, were very active in the two great Yiddish centers in America—in New York and in Chicago and also in other cities. And just as now, our theatre directors had their eye on the Yiddish actors and actresses who have distinguished themselves on the stage in Europe. Thus, it was then that they had their eye on them, and where there was a good Yiddish actor in Romania, in Russia, or in Galicia, they brought him here.

Little by little, the American theatre directors pilfered the Lemberg troupe and then Boris Thomashefsky sent a special emissary to bring Prager to New York. The special emissary was the famous comedian Berl Bernshteyn, who died some years ago.

Prager came to America with the idea that she would stay here not more than five or six months, and after that she would go back to Lemberg. This was at the end of August in the year 1895. Prager was sure that she could not stay long in America. It turned out though, that instead of the five or six months that she intended to stay, she has remained here, “temporarily,” a little longer—for another thirty-one years…Thus, Regina Prager made her first appearance in America thirty-one years ago, when the Yiddish theatre was beginning to settle here and when the first buds of the blooming epoch were already appearing, the epoch which brought a quite considerable number of fine and original talents to the Yiddish stage.

We usually assume that the first sacrifice that a person has to make to dedicate himself to the stage is faith. Indeed, in truth, most actors and actresses are quite superstitious; they have their own backstage rules, which are oftentimes quite ridiculous; some are convinced that before appearing on the stage, one should take the first step with the right foot, and if, God forbid, with the left, it is a certain failure. Others believe that when someone takes on the production of a new play, if he lays it on a bed, it will be sure to fail, and if he is holding the play in his hand and by chance it falls on the ground, it will surely be a great success and will bring in a lot of money. You will also find some actors and actresses who maintain that a play in which one of the heroes must break a plate or a lamp when he becomes angry is a sign of luck… and on and on, endless signs, that are accepted in the theatre world—so many signs that a person could write about them forever.

But all these particular signs are connected with professional superstition, and not with faith. The truth is this, that an actor cannot be pious. Life backstage and also on the stage puts the actor in such a position that he cannot be pious, and if he is, in the end he must sacrifice his piety on the altar of art. The only one who preserved her piety in the strictest manner is Madame Regina Prager. For the thirty-some years that she has been an actress, she never lit a match and never kindled a fire on Friday night or Saturday onstage. She not only kept the Sabbath, which for her was a holy day, but also the eve of the Sabbath. During all the years that she was on stage, on Friday she never rehearsed.

In the contracts that she signed with the theatres where she performed, she always inserted special items that other actresses did not include: the first night of Passover she would not perform; Rosh Hashana she would not perform; and when the troupe went on tour, she would not travel on the Sabbath. And the directors already knew that when they were concluding a contract with Madame Prager, they had to expect that she would add such details as were rather more customary for a rabbi’s wife than for an actress…

But they had no choice.

The first person who violated Madame Prager’s piety a little bit, and moreover, violated it so that she would take into account the fact that she was an actress, was L. [Leopold] Spachner, the husband of Madame Bertha Kalich. When he was connected with Yiddish theatre as a manager, he stubbornly insisted that Madame Prager must reckon with the circumstances and that she must remember that she is an actress and not a rabbi’s wife; she must perform on the Sabbath and she must perform on Rosh Hashana! “He prevailed,” Madame Prager moaned to me, and a sad smile spread over her face. “I will perform on the Sabbath, I will perform on the second day of Rosh Hashana; but if you give me a million, I will not perform on the first night of Passover!”

So in this case, she made a very small compromise with the Master of the Universe; she convinced Him that He would reckon with the fact that she was an actress, and at the same time she also would make Him a partner in her roles…without His help, she could not take her first step on the stage, and each time that she had to perform a new role, and she raised both hands to him and begged:

“God, don’t humiliate me!”

The Struggle between Young and Old Actors on the Yiddish Stage:

Regina Prager speaks on this subject, how the German Five Frankfurters was made into the Yiddish The Cantor’s Wife so that Regina Prager would have a good role.

—A love song that led to true love between Regina Prager and the man she married.

By M. Osherowitch, Forverts

Everyone reaches a moment in life when the present begins to become the past, and one begins to think seriously about the future. At such a moment, a person undergoes a great deal, and an actor or actress on the stage experiences even more. It begins when one ceases to play youthful roles and begins to play older ones … It is difficult to describe with words what an actress experiences the first time she plays the role of a mother or a grandmother after being accustomed for years to play roles of young girls…The youthful roles keep the actress young in life and the older roles draw a new line, that turns the present to the past…Just like many other actresses, Regina Prager had this experience. At the time, this made a very strong impression on her; and although she couldn’t accuse anyone, she was angry and indignant; she felt ill and depressed, just as a woman feels when she realizes that her head is becoming covered with gray hair and wrinkles begin to appear on her face…

But now, Regina Prager has already forgotten that negative impression; just as she was used to playing younger roles in the past, so now she is accustomed to the older ones, and she speaks about that time in the past with a smile on her face.

This is how that moment occurred:

A German play was produced in English in America by the name of The Five Frankfurters. The play was about the Rothschild family and it demonstrated how old Madame Rothschild spread her influence in far-off financial matters all over the world through her five sons, all great millionaires living in the great centers of Europe. Thanks to the fact that they were so rich and each of them lived in a different land—one in France, one in England, one in Germany, and so on—rulers bowed before them, rulers who had to turn to them for loans and as a result they, the five Rothschilds from Frankfurt, ruled over the entire world.

The play was running on Broadway at that time, and it was featured in many newspapers. It was the opinion of several critics that the play contained anti-Semitic tendencies, and that the writer intended to show that Jews are always seeking their own benefit and that they control international finance.

Then the thought occurred to Rumshinsky that he could make a genuine Yiddish play from The Five Frankfurters on a completely different basis. Instead of five Jewish millionaires who are the children of one mother and are spread out over the whole world, there would be five Jewish artists, great artists, singers, and musicians, who were also dispersed in different lands and were famous throughout the whole world. It would signify that the five Jews, all children of one mother, control not the finances of the world, but the arts of the world…The idea was a good one, and the operetta was created that was later so successful on the Yiddish stage—Di khaznte (The Cantor’s Wife)…

When the roles were being assigned, the question arose as to who should portray the cantor’s wife. It was vital that the actress who played the role could sing well and should have a beautiful voice. The subject of who should be given the role was under discussion, and then Rumshinsky said:

“The best woman for the role would be Madame Prager! I cannot imagine a better cantor’s wife.”

Everyone gazed in wonder at Rumshinsky—Prager as the cantor’s wife?! As the mother of five grown sons and the grandmother of grandchildren?!

“Yes, the role is perfect for her!” Rumshinsky maintained his belief. “She will be a big hit in this role. I am sure of it.”

And indeed, Madame Prager was a big hit in the role, but there are no words to describe what she experienced during the auditions for Di khaznte. At that point she suffered greatly, very greatly, because she knew and understood and felt that now began a new epoch in her career as an actress. From that time forward, she would never again play young roles on stage.

Di khaznte was a great success, and Madame Prager had a substantial part in it. She was very well received with her heartfelt singing and her fine acting. Possibly for the first time on the Yiddish stage, people saw something new—a prima donna in an older role, a prima donna as a mother, a prima donna as a grandmother, but one that can sing beautifully and act sincerely and naturally.

And from then on, the Yiddish operetta stage was enriched with a whole line of types of singing mothers that were created especially for Madame Prager, and she graced them with her genuine Yiddish singing, which even today still has in it the spirit of the Sabbath and holidays.

After Di khaznte had ended its run, for some time in the theatre they began to think about a play in which Madame Prager would have an opportunity to distinguish herself just as in Di khaznte. And then Rumshinsky again had a bright idea. The idea was that they should take the old play, Idishe kind(A Jewish Child) and they should redo it so that it would be called, Di rebetsin’s kohler (The Rabbi’s Wife’s Daughter). The operation that was done on Idishe kind (Jewish Child) was—one could say “bloody”— they cut passages from the play, ended monologues, changed the words, and turned everything around, so that Madame Prager would have a good role in the play, where she could do a lot of singing.

The core of the operation consisted in the fact that a rabbi from the old text was thrown out and in the new text, a rebitsin was in his place …

A ready-made role for Madame Prager!

Since she portrayed a cantor’s wife successfully, it seemed certain that she would successfully play a rabbi’s wife …

For Madame Prager, the role in the play was not new. She had already played it earlier, but not the rabbi’s wife; such a role did not exist there. There was only a rabbi, and the rabbi had a daughter, a young, beautiful girl. And she, Madame Prager, had earlier played the rabbi’s daughter in that play …

At the first rehearsal for the revamped play, a kind of quiet tragedy beyond words took place. Madame Prager, who always held herself quietly and modestly, did not know who would play her former role, the rabbi’s daughter, so she came to the rehearsal and sat quietly apart in a corner.

Among the actors and actresses who were coming to the rehearsal, she saw the young Lucy Finkel, who she remembered as a little girl of five or six.

“What are you doing here, Lucy?” Madame Prager asked her joyously. “Just look, you have gotten so big, may no harm befall you! Tell me, child, how are you? What are you doing?”

She spoke with her tenderly, as one speaks to a child. And as she was sitting with her and talking, suddenly she heard a voice:

“Lucy, rehearsal!”

Madame Prager remained sitting where she was, taken aback. Lucy is already at a rehearsal?! Lucy is already an actress?! What’s going on here? It seems to me at first that it was not long ago that Lucy was a little girl of five or six years old! It feels as though it was not that long ago that Lucy’s mother, Emma Finkel, was burning up the Yiddish stage, together with Sabina Vaynblat; they both, Emma and Sabina, were “the lively little pair” on the Yiddish stage … and now Lucy, Emma’s daughter was already a big girl and she had become an actress! … When did she grow up?! …

And sitting thus, lost in the years that had passed like a dream, Regina Prager heard how the young Lucy was rehearsing the role that she had performed earlier—the role of the rabbi’s daughter …

A shudder ran through her body. With a desolate spirit, she looked inward. Without speaking a word, she began to move nearer to Lucy in order to look at her more closely, as if she would persuade herself that this was not a dream; she had so much to say and yet she said not a word. Lucy’s voice sounded in her ears; she recognized the melody and the words that she herself had sung. Two generations were standing on the stage.

Feeling a deep pain in her heart and being powerfully surprised by what she was seeing now with her own eyes and hearing with her own ears, Madame Prager looked at Rumshinsky, and her mute glance without words said a great deal, really a great deal …

Rumshinsky’s heart constricted, and he also answered with a silent glance, that might have said:

“How can we help it? The years don’t stand in one place … A new generation is growing up.”

In the role of the rabbi’s daughter, Madame Prager used to sing a love song that was a big hit with the audience; now Lucy Finkel was singing the love song, and Madame Prager sang another song, “Hamavdil” (the blessing to end the Sabbath) that was more suitable for a rabbi’s wife.10 Rumshinsky wrote “Hamavdil” for her and it was a big hit with the audience, so that in a short time all the cantors in America were singing this “Hamavdil.”

And it will be no exaggeration to say that thanks to the fact that Madame Prager is what she is, Jewishness was more preserved, or to put it a better way, the Jewish tone of our operetta stage. With her personality, with her character as a performer and as a person, she generated the need for such suitable roles to be created for her in the operetta, that are authentically Jewish and where she would be called upon to sing melodies that are truly Jewish.

“We know,” Jacob Kalich said to me, one of the owners of the Second Avenue Theatre, where Madame Prager performs now, “We know that not only in life but also on the stage, she feels at home when she blesses the candles, when she says, ‘God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob’ when she speaks about the land of Israel, when she remembers the years gone by and when she sings a little Jewish song. So, we create such roles for her, and she is successful with them.”

So it was that Regina Prager accomplished quite a bit for the Yiddish operetta stage in America, where she arrived more than thirty years ago, and a substantial part of the time that she has been in America, there remained always a young man, who is now a completely gray-haired old man …

And here I must touch upon an intimate event in Madame Prager’s life.

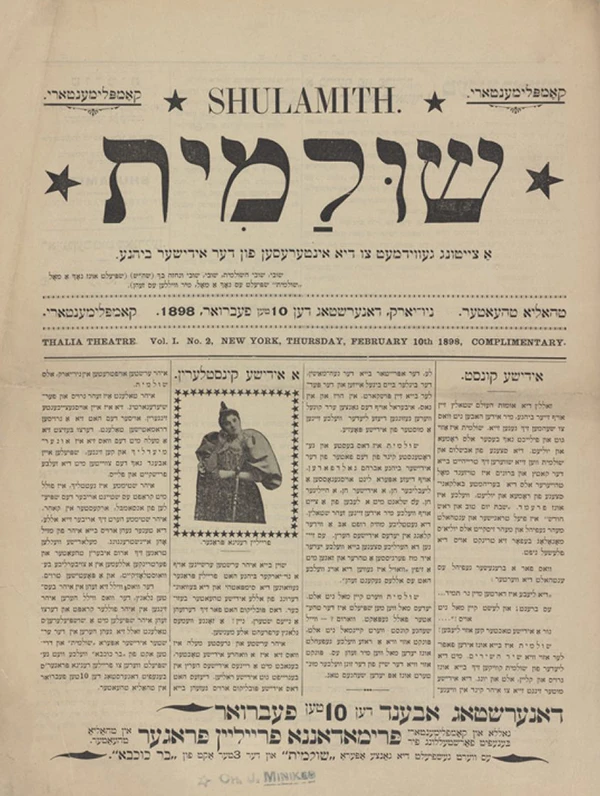

This was twenty-nine years ago. In the Thalia Theatre where Prager was performing, an Americanized Jewish young man by the name of Harry Weisberg began coming to almost every performance. No one knew why or for whom he came so often; a couple of times, people noticed that he came to the same play several times, but it didn’t occur to anyone to suspect him of something. Who cares if a young man comes to the theatre often! Maybe he really likes the play that’s being presented? Maybe he aspires to become a member of a claque? Or maybe he is simply a lonely young man who has nowhere else to go and nothing to do, so he comes to the theatre to while away a couple of hours! Didn’t he pay for his ticket? So, he should come often and amuse himself in good health. May he enjoy it!…

Only two people knew for whom Harry Weisberg came so often to the theatre. The two people were Weisberg’s own brother and his brother’s bride, a daughter of the well-known playwright of that time, Hurvits whom everyone called “the Professor”…

Harry Weisberg told them the secret, that he came so often to the theatre because of Regina Prager. She pleased him; it gave him great pleasure to see her on the stage, when he heard her sing…

“Maybe you’re in love with her?” his brother asked him.

“I don’t know.” he answered, a little ashamed. “I’m very afraid that I am.”

“So, why are you silent?” his brother’s wife asked him with a smile. “Ask me, I will introduce you to her.”

“So, I’m asking you.” Harry Weisberg answered.

Hurvits’s daughter was well-acquainted with Regina Prager, so once before a performance, she went to her backstage and said:

“Listen, Regina, today when you go on stage, look at the box that is on the right side.”

“For what purpose?” Regina Prager asked.

“What does it matter to you? Look!”

“But for what purpose?”

“You really want to know? All right, you’ll find out that there sits a young man who is madly in love with you.”

Regina Prager was slightly embarrassed, and although she said that it didn’t matter to her who the young man was, as she was leaving the stage, she sneaked a look at the box. Unfortunately, other young people were there who were looking at her, so she couldn’t tell who the young man was who was in love with her.

Once, at a performance of the play Khanele di finisherin (Hannah the Finisher) by Sigmund Feinman, Regina Prager, in a small role, had to sing a little song, a love waltz, that one of the Jewish composers had written for her. When she sang the song onstage, she suddenly felt as though someone was looking at her piercingly, as if he was really penetrating her through and through with his look. Then she stole a glance at the loge on the right side and saw a young man with a round face who never took his eyes off her.

This was pleasant to her; she felt the warmth of his glance and afterwards how he applauded vigorously, and when she had to sing the same little song again, she sang it for him and only for him…

And thus, that particular little song played a big role in Regina Prager’s life. The young man fell even more deeply in love with her; the same day, he was introduced to her—and the wedding was a short time later.

This is also one of the reasons why Regina Prager remained in America.

Twenty eight years have passed since she was married and she lives peacefully and happily with her husband, Harry Weisberg. They have two children, a daughter and a son, Fanny and Morrie.11 In addition, it is remarkable that she brought up her children with the idea that they would never go on the stage …

“For what purpose?” she says. “It is better that my children are not on the stage… Indeed, it is true that there is a lot of satisfaction in being on stage—the applause, the recognition, the esteem. But there’s a lot of vexation as well. And the strain! So, that is why I am pleased that my daughter, Fanny, has a fine voice and sings for herself and not for others; that’s why I am also happy that just three months ago she got married to a wealthy real estate agent, one Max Kalb, and I am also pleased that my son, Morrie, makes a living and is not an actor”.

Her life at home is separate from her life on the stage, though she loves the stage very much and its Jewish warmth fills her soul. “And so,” she says, “I will still remain for the whole time that is meant for me to be, an actress on the Yiddish stage.”

May she live long and maintain the Yiddish sound in Yiddish operetta!

“Regina Prager, the Rabbi’s Wife on Stage”12

By Joseph Rumshinsky

“On the Sabbath, holidays, and the New Moon, I pray for myself alone”—that is a little song from Shulamis, which Madame Prager often sang. The words of the song are very fitting for the sort of life and the personality of Madame Prager, but it was even more fitting that she should sing: “On the Sabbath, holidays, and day and night, I live for myself alone,” because theatre life, the noisy night life, women’s fashion, even theatre politics, the babbling of café nonsense and idle talk and love intrigues, had no effect on Madame Prager.

Tragedies, murders, weddings, legal and illegal loves played out before her eyes—it was as though she noticed none of it. To say it better, she more than noticed all of it — she even knew all the details, but it had no effect on her and made no impression at all. During the Days of Awe she was at the synagogue, and the rest of the year, she stayed at home. In the theatre, she sat in her little dressing room. Everywhere, she remained Madame Prager. She imposed on no one with her piety and modesty; but likewise, the entire theatre atmosphere had no effect on her.

“God, don’t humiliate me! I beg you, dear God, that you won’t humiliate me!” This was the prayer, this was the plea that Madame Prager used to say before each performance on the stage. With the words: “God, don’t humiliate me,” she spent her life on the stage for thirty-plus years.

In Russian operetta and opera, I used to see similar scenes. Many prima donnas and soubrettes such as Armatov, Tshelskaya, Dobrotini, would never go on stage before thoroughly crossing themselves. But this was pure hypocrisy on their part, as if they wanted to fool God, because they lived lives that were in no way holy … and indeed, those who led the most sinful lives crossed themselves the most.

But the case of Madame Prager was something completely different: she acted in accordance with her feelings. Her beliefs corresponded to her conduct.

Our great Yiddish artists, musicians, and writers are constantly doing us a favor by dwelling on our Yiddish street, and at every opportunity they threaten us that they will run off to the gentiles … they always have one foot with us and the other with the gentiles. Many Yiddish plays and novels are already a little crippled because they are written with a point of view that flatters the gentiles. But the gentiles send them back to us, and still they are continually doing us favors. Madame Prager is the antithesis of this because, as I discovered, her opportunities on the grand opera stage were vast, and I am certain that she could have been in the ranks of a Patti or a Sembrich or Tetrazzini. Her voice, besides being rich in color, strong, resonant but at the same time agreeable, had a naturally trained tone, which is the case with all great opera singers. But her reserved, pious, modest lifestyle was a great hindrance to her opera career.

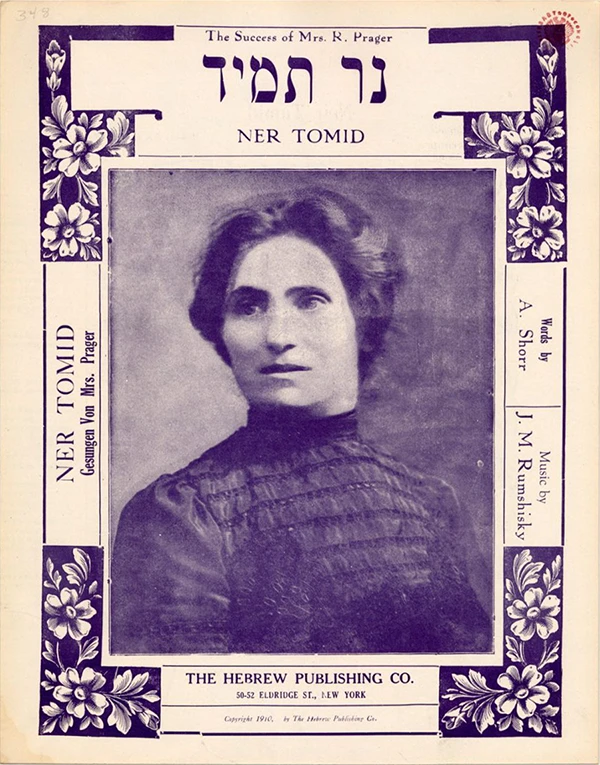

The Hebrew Publishing Co., New York, NY, 1910. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197833/.

Her voice had a dramatic, even, and resonant sound that could easily change into coloratura and staccatos and obtain the lightness and suppleness of a genuine lyric soprano. All of this enchanted her listeners. When she sang, a breathtaking stillness ruled the theatre until her last finale of a song or waltz-number, when it seemed to me that the whole theatre would collapse from the ovations and stormy applause.

In my lengthy career, I have loved, when I am conducting, to observe the audience, and very often, I get criticized for looking more at the audience than at the orchestra and the stage. I do this, because I am very curious to see how the public reacts to certain scenes and numbers. But at my most successful musical numbers, I have never yet seen a moment in which the entire theatre applauded. Even at the most ecstatic moments, there were always a few who sat as though it did not make any impression on them at all, as though they were not even there; but after Madame Prager sang an aria, a song, or a waltz, everyone, young and old, big and small—everyone’s hands, even their feet, were busy expressing enthusiasm for her voice. I’m not saying it was for her singing, because due to the fact that she didn’t have much training, she sometimes missed the correct breath and the correct intonation, but the richness of her tone, the timbre, her blessed throat was enchanting and the listener forgot everything; the house would thunder like cannons with applause. After such cries of “hurrah” and applause from the public, she would run away, as if she didn’t want to be noticed by anyone, to her little room, sit and look at a holy book or do something for her home. Her fear of God was reflected in her theatrical performance. When it came time on Friday night to bless the candles on the stage, she never kindled the lights in front of the audience—they had to be burning earlier, or they were kindled electrically.

She refused to perform on Rosh Hashana. And when she couldn’t help it and still had to perform, they had to delay the start of the daytime performance until Madame Prager returned from the synagogue, where she had a good cry and prayed earnestly to God.

The transition in Madame Prager’s career happened before my eyes—from the romantic leading lady role, to the singing-mother roles. It was I who brought this about, and it is likely that at first, she was a little angry at me, because no actor, and particularly no actress, will admit so quickly that it’s time to start playing older roles; and even such a reserved person as Madame Prager would not, at first, admit it so easily.

But immediately with her first singing-mother role, for which I wrote the music to Boris Thomashefsky’s text, Di khaznte, for her, those of us on stage, together with the public, felt that Madame Prager embraced the role—the holy, patriarchal figure of the cantor’s wife suited her. She spoke the pious words of the prose and sang the cantor’s wife’s melodies with such heart and soul, that people used to feel that she was delighted with the words that she spoke and sang, and that she was truly experiencing them.

“God, don’t humiliate me!” Madame Prager used these words every evening before her appearance on the stage, and with these words she retired from the stage, perhaps because she began to feel that the younger generation was waiting to take her place. But we can comfort her by saying that to our regret, although it has already been several years since she left the Yiddish stage, no other Madame Prager has appeared, not even an almost-Madame Prager.

Notes

- Published September 26, 29, and October 2, 1926 in the Forverts.

- M. Vohlgeshafen, Yiddish theatre impresario, in Zalmen Zylbercweig, ed., Leksikon fun yidishn teater, v. 1, 646.

- Khayim-Shmuel Lukatsher, Yiddish actor and Broder singer, in Zalmen Zylbercweig, ed., Leksikon fun yidishn teater, v. 1, 220.

- Sam Adler (1868-1925), Yiddish actor and Freemason (Zylbercweig, Zalmen. Leksikon fun yidishn teater, v. 1, pp. 30-31.)

- Kalmen Yovelir (Yuvelir) (b. 1863-), Yiddish actor and singer (Zylbercweig. v. 2, p. 909.)

- Berl Bernshteyn (1860-1922), Yiddish comic actor, singer, and dancer (Zylbercweig, v. 1, p. 207.)

- Samuel Tobias (Shmul Tabatshnikov) (1861-1930), Yiddish actor and singer (Zylbercweig, v. 2, p. 802)

- Peter (Pesakhye) Graf (b. 1873), Yiddish actor and singer. (Zylbercweig. V. 1, p. 525)

- Bertha Kalich (1874-1939), Yiddish actress. See https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/kalich-bertha and https://web.uwm.edu/yiddish-stage/search?search=bertha%20kalich

- “Hamavdil” by Joseph Rumshinsky, was published in sheet music by Metro Music in 1924 and recorded commercially by several artists.

- A 1915 New York State census form lists Harry Weisberg, age forty, born 1875 in Russia, Regina, age forty-two, and their daughter Fanny (sixteen) and son Moe (thirteen) living at 61 Second Ave. It lists Harry as “a theatrical manager” and Regina Prager as “a housewife.”

- Originally published in Joseph Rumshinsky, Klangen fun mayn lebn, Nyu-Yorḳ: A.Y. Biderman, aroysgegebn durkh der Sosayeti fun yidishe kompozitorn, 1944. 429–33.

Article Author(s)

Beth Dwoskin

Regina Prager was one of the first leading ladies of the Yiddish stage, known for her extraordinary operatic voice and her continued Jewish observance throughout her life.

Alyssa Quint

Alyssa Quint is Leo Charney Visiting Fellow at the Center for Israel Studies at Yeshiva University.