Grand Opera for Yiddish Speakers in Early Twentieth-Century America! Who Knew?!

IN THE SPRING of 1904, New York witnessed the unlikely spectacle of a musical-dramatic adaptation of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal—in Yiddish. In the fall of that same year, Lower East Side audiences were offered a season of grand operas in Yiddish translation.1 Over the next twenty years, many Yiddish newspapers and magazines in the US published all manner of articles about opera. Two Yiddish books, one from 1907 and one from 1923, featured synopses of dozens of operas. In the 1920s, a weekly radio program presented abridged operas translated into Yiddish. This is merely a small sample of the evidence pointing to Yiddish speakers’ interest in opera in early twentieth-century America.

These endeavors to bring opera to a Yiddish-speaking public might seem at odds with the genre’s notorious elitism. Since the late 1800s, opera in America has been widely viewed as a refined and exclusive form of high culture, patronized by social and cultural elites. This highbrow reputation has spurred countless efforts to popularize opera over the last century, some of which were aimed specifically at Yiddish speakers. The approach to these various Yiddish-language undertakings moved in tandem with broader trends in democratizing opera at the time, shifting gradually from a Progressive Era emphasis on so-called “cultural uplift” in the first two decades of the twentieth century to an emphasis on the integration of high and popular culture as mass media changed the cultural landscape.

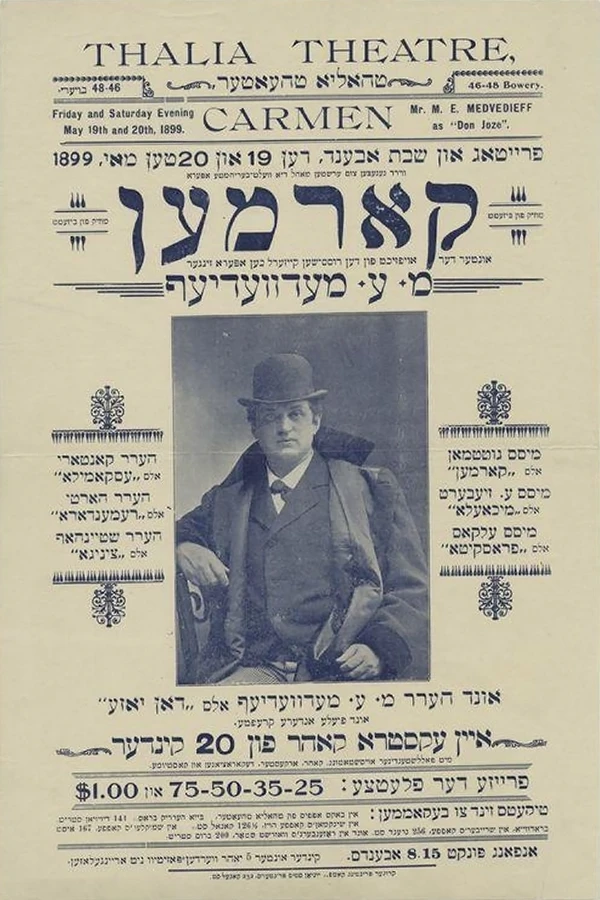

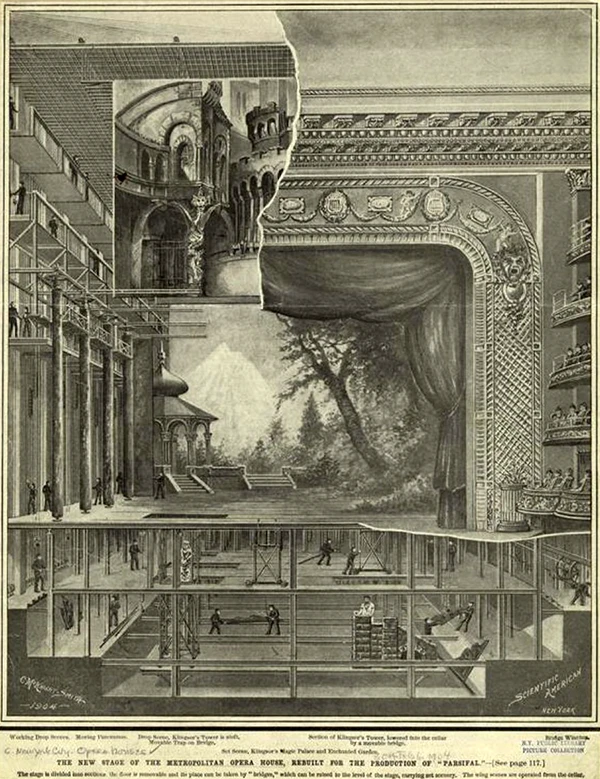

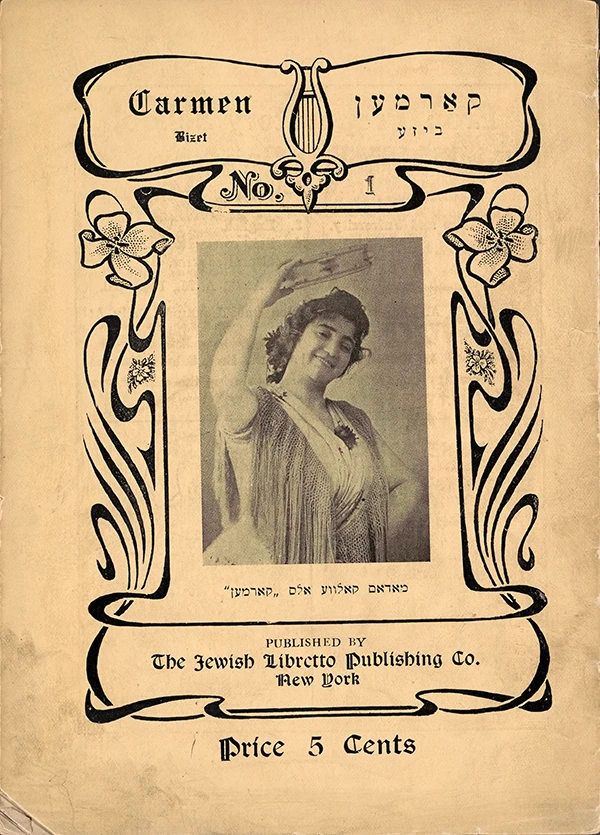

In early Progressive Era New York—America’s undisputed cultural center cultural center and hub of Jewish life—there was a brief surge of interest in opera in Yiddish translation. The frenzy surrounding the Metropolitan Opera’s controversial premiere of Parsifal in December 1903 spurred Boris Thomashefsky’s Yiddish version at the People’s Theatre a few months later.2 Not to be outdone, his rival, “Professor” Moyshe Hurwitz, staged nine weeks of opera in Yiddish translation in the fall of 1904 at the Windsor Theatre. Referring to the Windsor as the “Yiddish Metropolitan Opera House,” Hurwitz offered Yiddish versions of La Juive, Il Trovatore, Carmen, Cavalleria rusticana, Pagliacci, Aida, and Rigoletto. These productions appear to have cut and modified the originals, turning the recitative into spoken dialogue, and including only a handful of sung arias and ensembles. (Although few traces remain of these productions, libretti for two different Yiddish versions of Carmen have survived, offering a window into what some of these productions might have been like.)

Yiddish speakers at the time were also evidently interested in opera in languages besides Yiddish. As early as 1904, Jewish Lower East Side residents were known for attending performances at the Metropolitan Opera.3 Ads for opera in English also appeared in the Yiddish press, such as the 1906 notice in the Fraye arbeter shtime (Free Voice of Labor) for the Theodore Drury Grand Opera Company, an all-black troupe. From 1913 to 1915, the Zuro Opera Company, which appears to have sung in Italian, also performed in Lower East Side theatres.

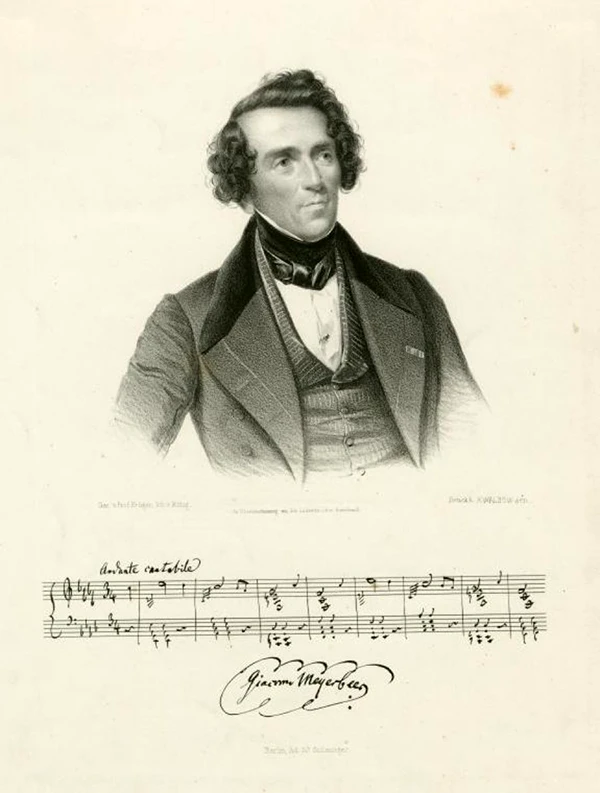

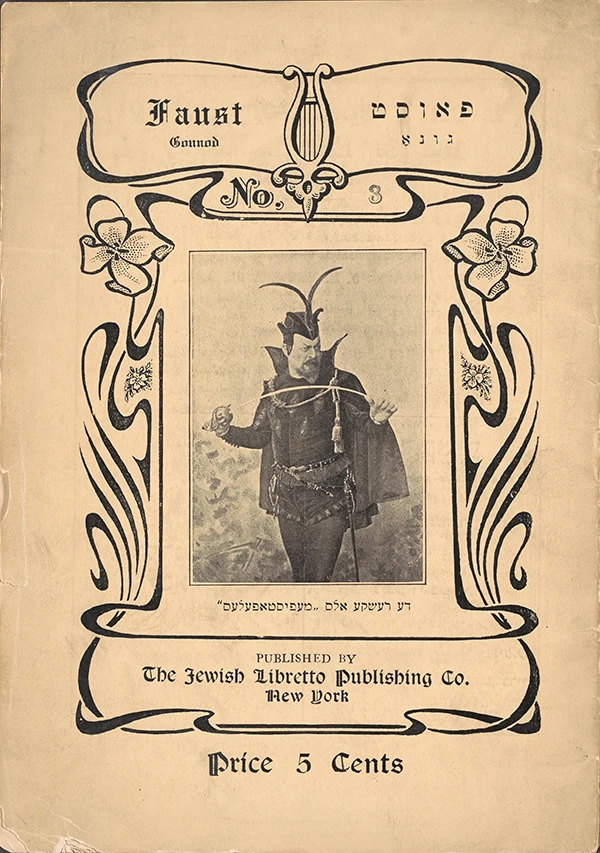

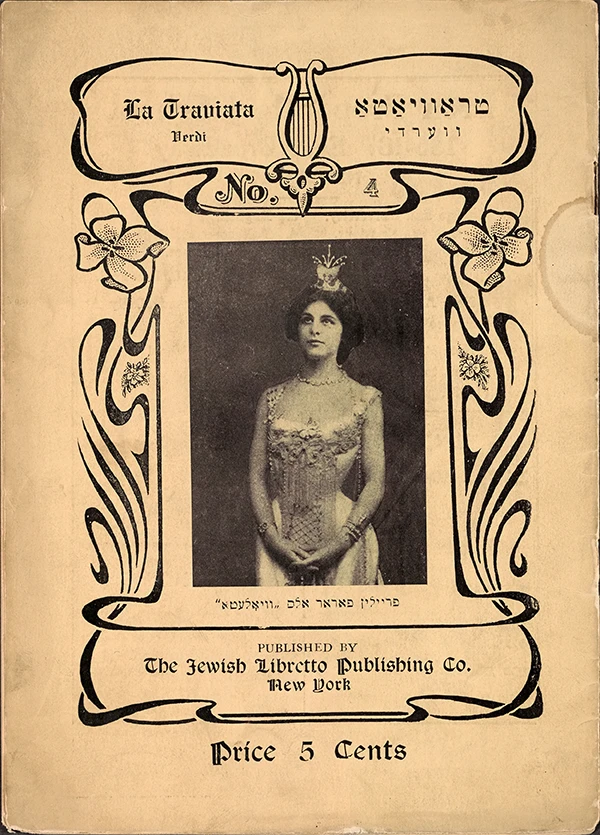

Books about opera as well as articles in newspapers and magazines provided growing opportunities for the Yiddish-speaking public to read and learn about the genre. In 1904, the literary journal Di Tsukunft (The Future) ran a biographical article about Verdi (a translation of a book chapter by Elbert Hubbard), coinciding perfectly with the first of the Windsor’s Yiddish-language Verdi productions.In 1907, William Edlin published a 300-page book entitled Velt-berihmte operas (World-Famous Operas), featuring detailed descriptions and discussions of the plots, music, and historical context of twenty-five Italian, French, and German operas.4 That same year, Philip Krantz published a biography of Giacomo Meyerbeer, entitled “Meyerbeer: The Opera King.” In 1908, the Jewish Libretto Publishing Company printed five-cent booklets of opera libretti such as Faust, Carmen, and La Traviata translated into Yiddish by Hillel Vikhnin, which also included commentary on the operas. From November 1909 through April 1910, Thomashefsky’s Di Yiddishe bihne (The Jewish Stage), a weekly newspaper focusing on drama and music, with special attention to Yiddish theatre and Jewish artists, published around two dozen articles on opera topics.5 Countless other opera-related articles appeared in general interest Yiddish newspapers like Morgen-zhurnal (The Morning Journal) and the Forverts (Forward) in the first two decades of the century.

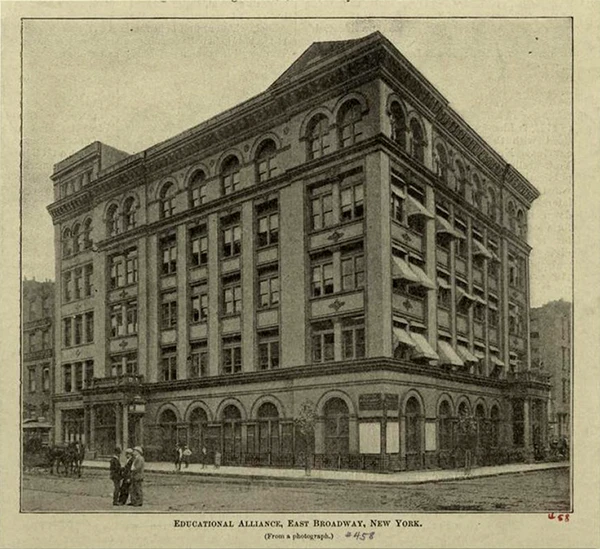

These many endeavors formed part of broader Progressive Era efforts to democratize opera and other forms of high culture. During this period, impresarios, producers, and other cultural leaders promoted greater access to opera, often underscoring its ability to uplift audiences—that is, to enlighten, educate, and refine. Organizations like the Educational Alliance provided immigrants in particular with a wide array of lectures and courses on uplifting high-culture topics, including opera. By the 1910s, the Jews of the Lower East Side had a reputation for being avid consumers of such educational offerings.

The widely-held belief in art’s capacity for uplift extended well beyond mainstream American culture. In the 1890s, a small group of socialist and anarchist Russian-Jewish elites began a movement to reform the Yiddish theatre, seeking to replace shund (trash) entertainment with more highbrow offerings—both new creations and adaptations of the best European dramas. According to the movement’s leader, the playwright Jacob Gordin, Yiddish theatre reformers wanted to “utilize the theatre for higher purposes; to derive from it not only amusement but education, not merely entertainment but the highest aesthetical enjoyment.”6

The new technology of recording that emerged around 1900 further increased access to high culture such as opera, bringing it into the sphere of mass media. During these years, records of opera arias were popular among Yiddish speakers: phonograph ads often listed the most recently released opera recordings, including ones in Yiddish.7 The Yiddish-speaking public’s interest in opera can also be seen in the comparisons of prominent cantors to opera singers—at least three cantors, Joseph Schmidt, Gershon Sirota, and Yossele Rosenblatt, all of whom also sang operatic music, were at times referred to as “the Jewish Caruso.” Some cantors in the 1920s, including Joseph Shlisky and Joseph Winogradoff, made recordings of opera arias, a few of which were in Yiddish.

The advent of radio offered yet another avenue for democratizing opera. Many radio programs of the twenties and thirties featured opera excerpts, and some presented abridged operas in both English and other languages, including Yiddish.8 For a few months in late 1929, listeners could tune into the weekly Robert Burns Yidishe Shtunde (Robert Burns’ Yiddish Hour).9 Advertised in the Forverts with the big headline, “Operas in Yiddish,” these broadcasts appear to have been abridged versions of grand operas, probably with a narrator reading out the storyline in Yiddish and singers (from the Marbini-Marchetti Opera Company) performing selected arias accompanied by an orchestra.10 The program also featured a lecture in Yiddish on topics of general Jewish interest, or sometimes even a comic monologue.

A further instance of Yiddish-language opera popularizing efforts during this period is Dr. A. Muzikant’s 1923 Dos naye opera bukh (The New Opera Book), which contained concise synopses of forty grand operas.11 In seeking, as he explains, “to give the readers of the book the essence, the whole substance, the whole sap, the whole soul of each opera text,” he takes an unorthodox approach.12 Rather than paraphrasing the plots and providing contextualizing historical information, Muzikant presents a sort of play-by-play of selected events, including some of the most important arias nearly verbatim. This strategy vividly highlights the key elements of the stories, thus emphasizing opera’s capacity for dramatic and dynamic storytelling.

The democratization of high culture via mass media heralded the beginning of the ideological move away from uplift toward integration, as purveyors of opera or opera-related material sought to incorporate it into the popular sphere, often avoiding drawing attention to opera’s elite associations. In both Yiddish and wider American circles, this meant changing the genre to make it fit within the parameters and expectations of popular culture, such as by disseminating it as excerpts (usually arias), significantly abridging or otherwise modifying it, or combining and juxtaposing it with unmistakably popular cultural forms.

Whether Yiddish was the language of the opera or the language of discussion about opera performed in other languages, there was clearly interest in the genre among Yiddish-speaking immigrants in America in the early years of the twentieth century. The existence of this Yiddish-language opera scene also reveals a tension between a desire to maintain ties to a minority-group linguistic tradition, and an impulse to fit into broader American culture. Hearing and learning about opera in the mame-loshn mixed past and present, foreign and familiar, Old World and New.

Notes

- The term “grand opera” during this period referred to canonic Continental European operas sung throughout (as opposed to light opera that included spoken dialogue).

- For more details on the Yiddish Parsifal, see Daniela Smolov Levy, “Parsifal in Yiddish? Why Not?”, The Musical Quarterly 97, no. 2 (2014): 140-80, https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdu007.

- In 1904, the New York Sunday Telegraph observed that “the East Side patronage of [the Metropolitan Opera], […], as is well known, has always been a very heavy one.” Bernard G. Richards, “Real Grand Opera in New York’s Ghetto,” New York Sunday Telegraph, September 18, 1904. Regarding Jews’ interest in opera on popular price nights at the Metropolitan Opera, see Edmund J. James, The Immigrant Jew in America (New York : B.F. Buck, 1907), 224.

- Many of these opera summaries had already appeared as newspaper articles in the Yiddish newspaper Der Amerikaner over the course of 1907.

- These included not only reporting on the most prominent affairs of the American opera world of the day, but also singer and composer biographies, musical criticism, and even technical discussions of voice quality, voice production, and singing style.

- Cited in Judith Thissen, “Reconsidering the Decline of the New York Yiddish Theatre in the Early 1900s,” Theatre Survey 44, no. 2 (2003): 177.

- Ari Kelman, Station Identification: A Cultural History of Yiddish Radio in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 247, fn. 72.

- The Metropolitan Opera’s broadcasts of complete operas, which began in the 1930s, were an exception to the usually short length of radio programs.

- For a discussion of the broader cultural context of this and other radio programs in Yiddish, see Kelman, Station Identification.

- The productions were directed by Rubin Goldberg, who was among the first major stars on Yiddish radio. Instrumental music was provided by an orchestra called the “Homophonic Ensemble,” conducted by Nathan Tsiganeri. The Marbini-Marchetti Opera Company also gave stage performances of popular-price grand opera in addition to appearing on the radio on the “Vim Hour.” Given the Italian names of the singers in the company, it would be surprising if all the arias on the Robert Burns show were performed in Yiddish translation, but the September 17, 1929 Forverts ad, for example, explicitly states that “arias will be sung in Yiddish.”

- A. Muzikant was one of the many pen names of Shaye Rozenberg.

- Emphasis in the original.

Article Author(s)