“Entertainment”?

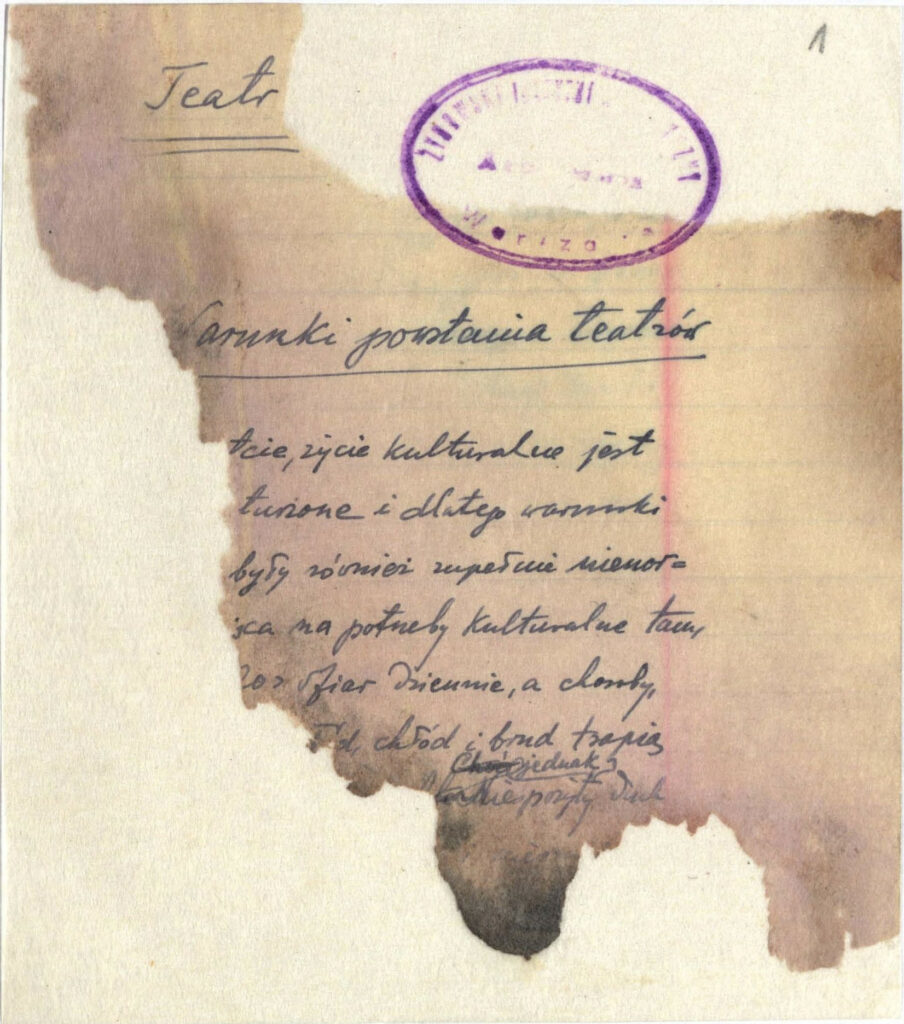

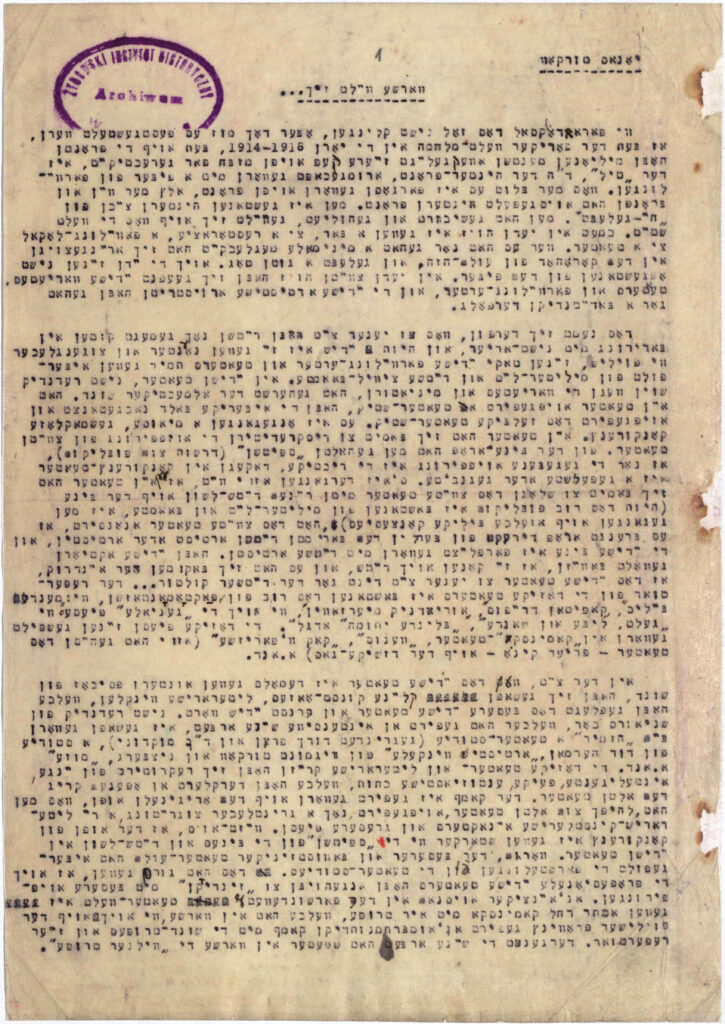

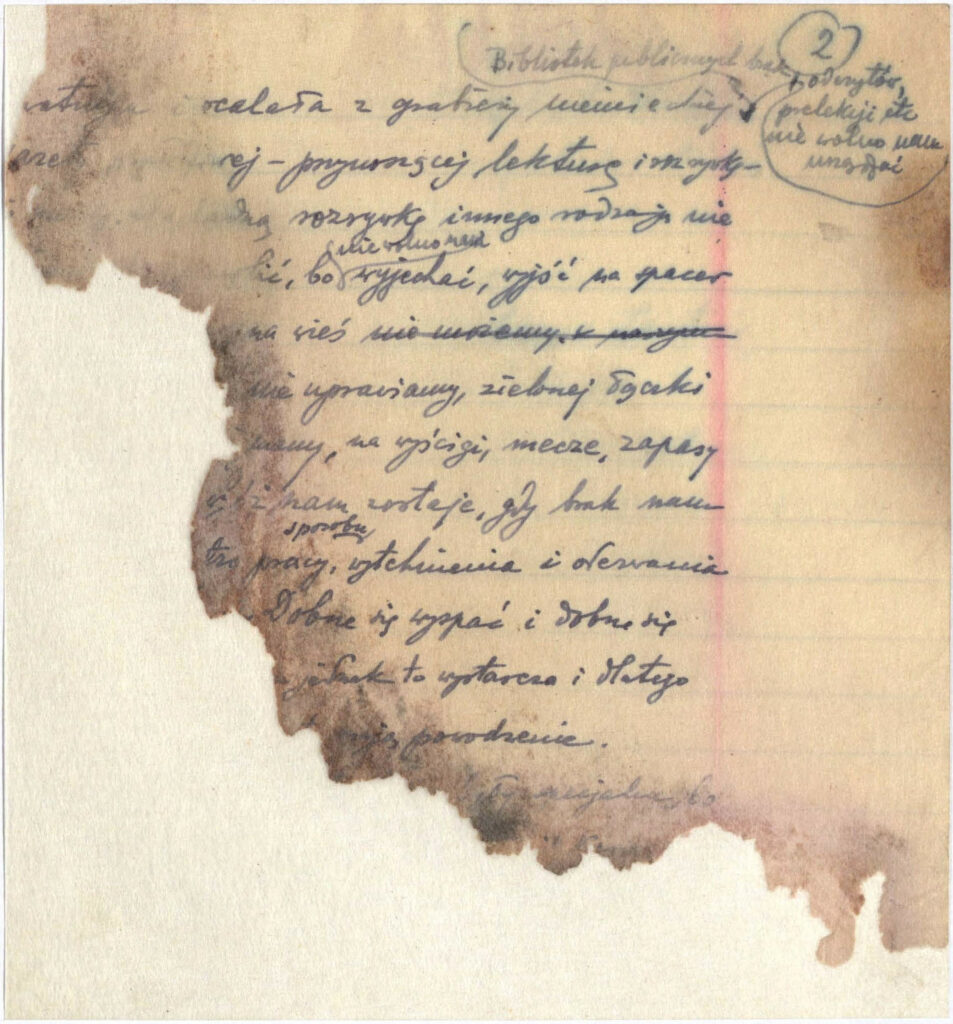

OVER THE PAST year, as time has permitted, I’ve been revisiting the subject of theatre in the Warsaw Ghetto. This has been enabled by recently available direct online access to the Oyneg Shabbes Archives, established in the ghetto by Emmanuel Ringelblum, now housed at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. It’s been an extraordinary experience to view the mildewed, often torn and burnt scraps of paper, along with an excellent transcription, on the 11-inch screen of my laptop.

I’ve focused on the texts of two witnesses, Jonas Turkow and Stanisław Różycki. Turkow, well-known as an actor, director and activist in the prewar Yiddish theatre, completed a summary of theatre activity in the ghetto in the first half of 1941. He was himself a major figure in the activity he describes. Turkow survived the war and later wrote extensively about his experiences (Azoy iz es geven: Khurbm varshe, Buenos Aires, 1948). His ghetto account differs in some interesting ways from his postwar writings. We know much less about Stanisław Różycki. Probably a school teacher before the war, Różycki wrote about everything he encountered in the ghetto, including street life, theatres and cafés, with penetrating precision in a fine literary Polish. He was murdered during the Great Deportation or perhaps somewhat later.

The single most controversial issue in prewar Yiddish theatre discourse was the subject of shund, referring to so-called trash, theatre that was judged to be “mere entertainment,” and poor entertainment at that, filled with singing and dancing, badly acted and frequently vulgar. This was contrasted with the productions of “serious” or “dramatic” or “artistic” theatre. The goal of activists, including Jonas Turkow, was the creation of a Yiddish theatre that could compare with the great national theatres of Europe. Today, following our contemporary interest in popular culture, this distinction, so important in the prewar years, has begun to lose its rationale. Drawing a hard line between shund and art has begun to feel pretty dated.

What’s extraordinary when looking at theatre in the Warsaw Ghetto is not just the continuity of this distinction but its intensification. While in the prewar years there was already an ethical component to this distinction, in the ghetto it became central. This was an individual ethics, but also collective and therefore political as well. A “better” theatre was better because first, amidst the radical immorality of daily life in a world built on obliviousness to the suffering and death of others, this theatre recalled its audience to humanity. And more: it was the ghetto underworld of smugglers, black marketeers and informers who invested in the shund theatres, while the “better” theatres functioned under the auspicies of the Aleynhilf, the self-help organization directed by Ringelblum. The cultural wing of this organization continued to see in all the activity it sponsored, as Ringelblum put it days before he died, “a weapon in the battle against barbarism.” Indeed, some of those associated with this work later fought in the ghetto uprising.

Article Author(s)