Being Shmutzik in the COVID Time

Those who attend the Association for Jewish Studies conference regularly couldn’t help but notice that things were different at the December 2020 meeting. Yes, everything was online. Yes, sessions were shorter and almost everyone had visuals. But the most notable difference was a shift in what an academic conference paper could look like. Presentations became performance. Nowhere was this more obvious than in the session called “Visioning New Worlds and Recalling the Old World in Queer Yiddish Drag and Burlesque.”

The group that led this session, Washington DC’s Shmutzik Shmates, is not even the only queer Yiddish drag or burlesque troupe around. Boston has Turmohel (pronounced “turmoil”) and individual performers like Shane Baker in New York have added drag personas to their practice (in Baker’s case, the bilingual, singing storyteller Mitzi Manna). They all seem to have arisen simultaneously, with most starting to perform publicly in 2019. Suddenly, we have a bona fide new cultural form, emerging from both the mainstreaming of drag and the expansion of it as an art form that includes many genders and creative practices. Yiddish cross-dressing isn’t a recent phenomenon, but its explicit connection to drag, to gender and sexual identity, and to social justice movements is.

After atttending the AJS session, I spoke with the members of the Shmutzik Shmates, to investigate how they use Yiddish cultural phenomena to illuminate culturally-rooted ideas about bodies, genders, desire, transgression, and to find the spaces where queerness can be spoken and seen. The three Shmates are Brenda Roses (she/her), Kasha Varnishkes (they/them), and Bikher Dik (he/him). Each of them brings different expertise to the group. Brenda Roses has a background in burlesque, Kasha Varnishkes is connected to arts and performance communities in DC, and Bikher Dik is a Yiddish speaker.

They met through political action, and continue to work together politically in a variety of Jewish and non-Jewish social justice movements. They all worked on “Occupation Free DC,” an effort to end exchanges between police in Israel and Washington, DC. They took part in a queer Yiddish dance protest outside Stephen Miller’s apartment in which Yiddish insults were hurled. In this work, as in their drag, they “imagine alternative ancestors”: particularly, a queer, anti-fascist lineage which buoys them in the difficult work of organizing. Due to COVID, mutual aid has become a central part of their work, and this begins in their work with each other. Their artistic work explores conflict, trauma and harm, Kasha Varnishkes tells me, which requires intense support between the three of them.

They have chosen to call their performance work “Yiddish” rather than “Jewish” to acknowledge there are many histories of Jewishness, only some of which are white and Ashkenazi. By being as specific as possible, they leave the door open for other forms of Jewish drag. They also acknowledge that they are far from experts on anything Jewish at all: Brenda Roses counts this as one of their greatest transgressions. They claim Yiddish and Jewishness without having to become experts: instead, they use “knowledge that we have in the body,” Brenda Roses says. “Things are stored in our bodies that we might not have the words for or the intellectual capacity to express.”

At the AJS conference, the Shmutzik Shmates presented several pieces on video, including a re-imagining of the role of the Jewish housewife, a piece which unfolds under a soundscape of sampled clips of Adrienne Cooper singing “Baleboste.” In this piece, Brenda Roses is a femme top who gets stuff done: Kasha Varnishkes and Bikher Dik do her bidding to create a Shabbes tish. The video was shot at a Black, queer social business called Check It Enterprises, which has an outdoor performance space. In front of a mural promoting statehood for DC, the stateless language of Yiddish is cheered on by an audience connecting to an erotic vision of Shabbes: where rituals feel good, and can be made better by rubbing or holding a candle between your legs, or feeling the warmth and pain of melting wax. At the apex of the piece, Kasha Varnishkes holds the two challahs to their butt, dancing provocatively. The audience gasps and cheers. Is celebrating Shabbes as joyful as eating butt? Is it as passionate as a threesome where genders don’t conform? Acknowledging the erotics of religious ritual isn’t intended to degrade these traditions. In their vision, the physical pleasure of the rituals can’t be separated from its holiness.

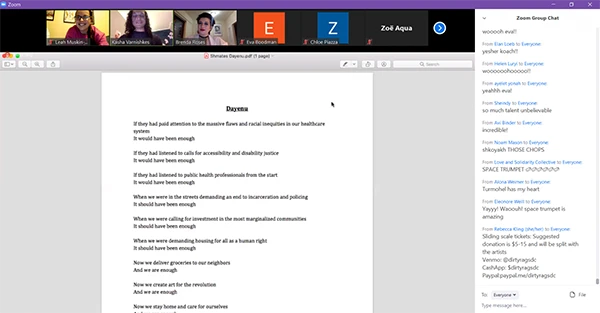

Since the beginning of COVID, the Shmutzik Shmates have held workshops and performances via Zoom, starting only a few weeks into pandemic restrictions with a Pesach show. The decentralized format allowed them to collaborate with Turmohel in Boston, the feminist Klezmer band Tsibele in Brooklyn, and Berkeley PhD candidate Julia Havard, who studies intersectionality in drag and burlesque. They used effects ranging from the low-tech (if you put a drinking glass in front of your camera, it makes a warped visual that evokes old television time travel) to more complex interslicing of live and pre-recorded pieces. “With in-person shows, you take for granted that people are going to feel present,” Brenda Roses says. “For a Zoom show you have to be way more intentional about the container you are creating for people.” They also ramped up their accessibility game. They use live-captioning, interpretation and translations, often using the chat function. They are committed to increasing their accessible supports when they return to live theatre.

“I feel very excited about the way Zoom enabled people to come together across different geographic locations and defy borders,” Bikher Dik says. “It feels important to think about diaspora, creating vibrant diaspora communities…so I wonder if even if we do in-person pieces there will be ways that we can incorporate collaborations with our comrades from all over.”

What becomes clear, as I watch their performances and talk to these young activistists, is how much has changed with the rise of drag. It enlivens academic conferences, it surfaces hidden queer life, it allows new art forms to reach out in unexpected directions. In drawing on specific Ashkenazic tropes, the drag and burlesque of the Shmutzik Shmates invites audiences interested in queer erotics to consider Yiddish, and asks the usual audiences for Yiddish culture to reconsider it as a space where queerness pulses.

Article Author(s)

Faith Jones

Faith Jones is a librarian, translator, and researcher in Vancouver, Canada. Her work focuses on gender in Yiddish culture. She is currently working on a book-length translation of stories by Soviet author Shira Gorshman.