Studying Great Lakes half a world apart

Maxon Ngochera wanted to research Lake Malawi, part of the African Great Lakes system, while working toward his doctorate. To do so, he enrolled in a graduate school 8,500 miles away.

At UWM’s School of Freshwater Sciences, located on the shore of Lake Michigan, Ngochera could compare Great Lakes half a world apart. He completed his doctorate in 2018, and it’s served him well in his home country as chief research officer in Malawi’s Department of Fisheries.

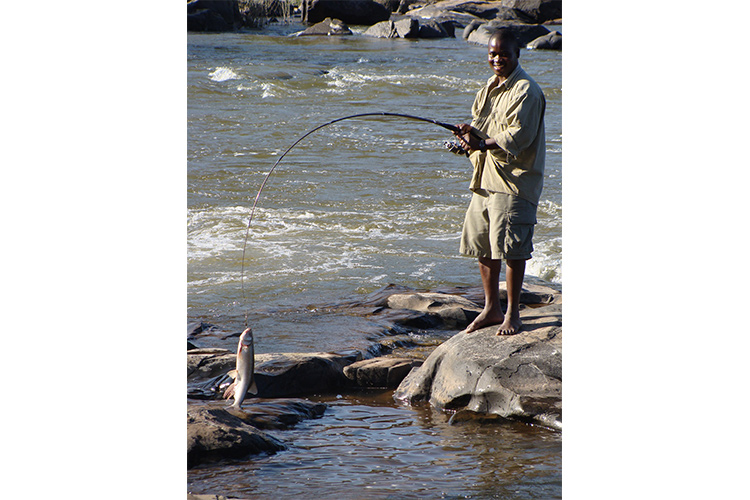

“Managing a freshwater Great Lake, whether it happens to be in Africa or the United States, means protecting the public’s drinking water, food source and ecological cornerstone,” Ngochera says. “In Malawi, fisheries are huge, and I wanted to contribute something.”

At UWM, Ngochera found the perfect mentor in Harvey Bootsma. The associate professor is researching the effects of climate change and other stressors on large freshwater lakes, particularly Lake Michigan. Bootsma also makes frequent trips to study the African Great Lakes.

Lake Malawi is far deeper than Lake Michigan, and in parts of the African lake, the water column never completely mixes. This is because significant temperature differences between the warm top and cool bottom waters isolate those layers.

Without mixing, there is no oxygen in the bottom layer, but there is lots of carbon dioxide (CO2), which is produced by plankton that sink and decay. Fish can only live in the upper and middle layers of the lake.

Ngochera wanted to know how the cycling of the lake’s CO2 is affected by climate change and how it might impact Lake Malawi’s food web.

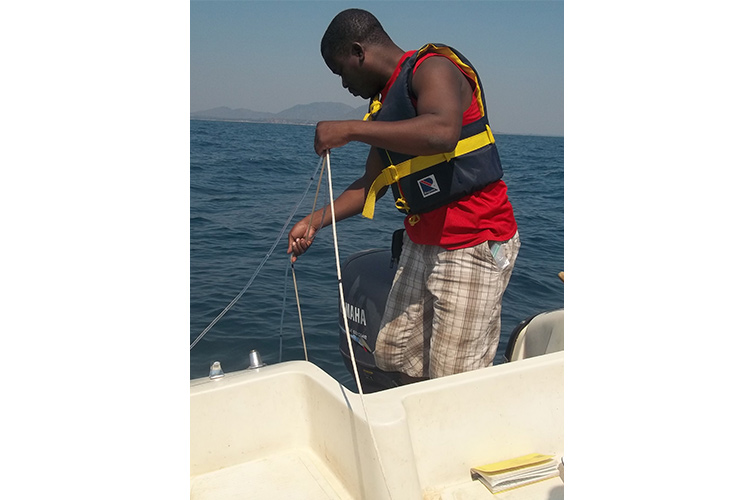

To track conditions in Lake Malawi, he borrowed an idea Bootsma has used to gather Lake Michigan data. Ngochera enlisted a ferry that crisscrossed the lake to collect information on water conditions, including CO2 levels and temperatures, at regular intervals over a one-year period.

He discovered Lake Malawi is a “carbon sink” – meaning it takes in more CO2 from the atmosphere than it gives off – and it’s better at doing this than Lake Michigan. This is good news for Lake Malawi’s fisheries.

“If the lake is a sink, there will be more food,” Ngochera says. “Maybe not the entire lake. Some areas are more productive than others.”

He says more research is needed to determine how the increasing temperatures of its surface water will affect Lake Malawi’s stratification issues. But in the meantime, the data is informing policymakers.

“Now we can tell investors where to put resources,” Ngochera says.