Before UW-Milwaukee achieved top rankings for research productivity in 2016, there was “major university status” – a goal UWM administrators and educators approached with vigor, creativity and strategy in the late 60s and early 70s. Key to achieving this status was focused growth in several areas of excellence: freshwater, urban, humanities and surface studies.

Opened in 1968 as one of the first humanities research centers in the United States, UWM’s Center for 20th Century Studies was a lynchpin of the university’s growing reputation. In 1971, university leaders dubbed the center one of the four “peaks of excellence” that became guideposts on UWM’s journey to top-research status. Nationally, the center became known as a groundbreaking gathering place where scholars and artists from all over the world came together for conversation, collaboration and exhibition.

“From the time I started graduate school at Berkeley in the mid-1970s, I knew about UWM from the Center for 20th Century Studies and the modern studies doctoral program, both of which were on the cutting edge of critical theory,” said Richard Grusin, center director and UWM distinguished professor of English. “All of the most famous thinkers and many famous artists and writers came through Milwaukee in the center’s first decades.”

Guests of the center over the years have included artists Nam June Paik, Dick Higgins of Fluxus, Laurie Anderson and John Cage; theorists Stuart Hall, Teresa de Lauretis, Jean Francois Lyotard, Judith Butler, and Jean Baudrillard; authors Anaïs Nin and Eugene Ionesco; and filmmakers Isaac Julien and Frederick Wiseman.

Time has changed the center. In 2001, it received an updated name: the Center for 21st Century Studies, or C21. In another nod to the passage of time and technology, the center has broadened its focus to encompass digital humanities. Today, the center organizes its research and public programs around three broad areas: critical, public and digital humanities, connecting them to today’s most pressing social and political issues.

One constant across the decades: All C21 events are free and open to the public, including the center’s 50th anniversary symposium. On Friday, Oct. 26, scholars from UWM, Columbia University, Amherst College, the University of Southern California and elsewhere will gather at UWM to present a series of research talks and commemorations in honor of C21’s golden anniversary.

“I’m excited to bring back to campus some of the key faculty and most successful graduates from the center,” Grusin said.

But first, Grusin and C21 Deputy Director Maureen Ryan have curated a deep dive into the center’s past, rounding up a collection of images and summaries of some of the center’s greatest moments and most influential figures from 1968 to today.

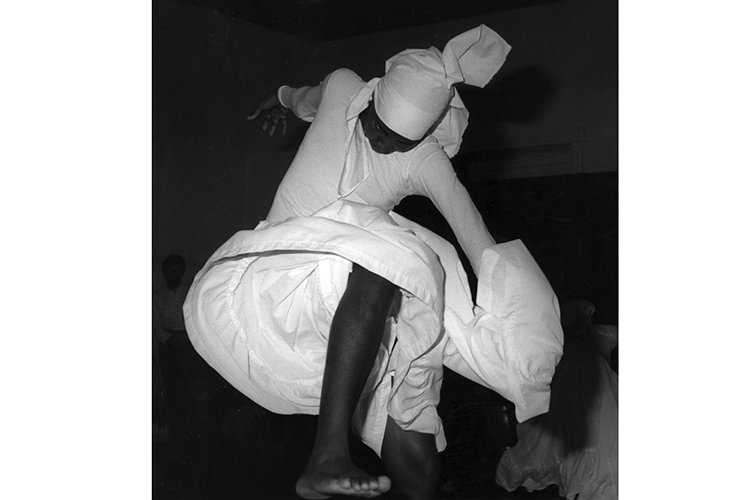

Ko-Thi Dance Company and Lavinia Williams, ‘Caribbean Suite’

March 17, 1983: Lavinia Williams was a dance pioneer. Born in Pennsylvania, she became a ballerina after high school but spent much of her life mastering Caribbean dance, developing national dance schools in Caribbean nations and teaching Caribbean dance in the U.S. Williams’ talk at the center was accompanied by a performance of “Caribbean Suite” by Ko-Thi Dance Company, a Milwaukee institution that performs the dance traditions of the African diaspora (and they are still going strong today). The event was part of “Black Performance in the New World,” a series of events held throughout March at the center that year.

‘Television: Representation, Audience, Industry’

April 13-15, 1988: This television studies conference was one of the first of its kind, with the center helping to kick off the discipline. Three days of lectures and panels included film, media and television scholars who would go on to establish and define TV studies as an academic field. Attendees included Mary Ann Doane, Patrice Petro, Lynn Spigel, Judith Barry, Charlotte Brundson and others.

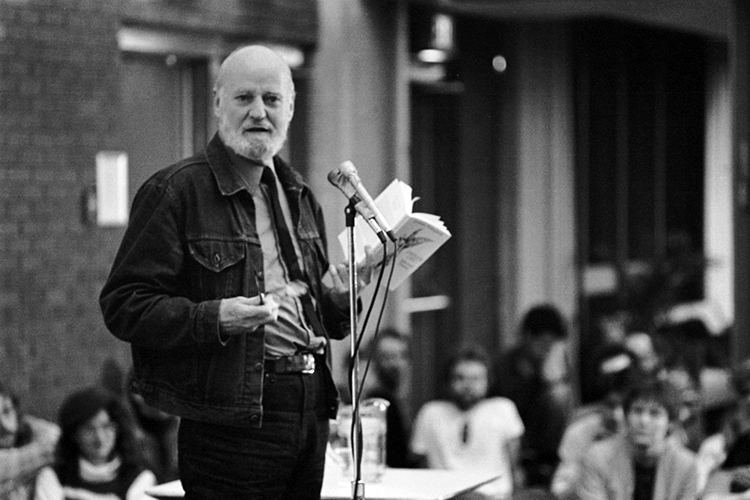

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, reading and open discussion

Nov. 27, 1984: Founder of City Lights bookstore and author of “A Coney Island for the Mind,” Lawrence Ferlinghetti is a major figure in 20th-century American poetry. Through City Lights Publishers, Ferlinghetti published some of the most influential writers of the Beat generation, including Allen Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara, Diane di Prima, and others. In 1957, Ferlinghetti and City Lights were put on trial in the landmark obscenity case over Ginsberg’s “Howl and Other Poems” — a case which set precedent ensuring First Amendment protection for many previously banned books.

Ferlinghetti read from his own poetry and discussed everything from the writing process to publishing and First Amendment issues related to censorship.

Stelarc, demonstration and lecture

Sept. 29, 1995: Legendary Australian performance artist Stelarc augments his own body with medical and technological apparatuses to extend its capabilities. He visited the center to give a demo of his “Third Hand,” a robotic mechanism that was worn over his own arm and controlled by his muscle signals. Later, in 2006, Stelarc would have a prosthetic ear surgically inserted into his arm that he (and others) can use to listen to other places, in an act of distributed global interconnectedness.

‘The Lost Art of Healing,’ art installation

April 24-May 18, 1997: A collaboration between the center and the University Art Museum in Mitchell Hall, “The Lost Art of Healing” was part conference, part art installation that explored the connections between medicine, aging and the body. As part of the installation, physician-artist Eric Avery gave lectures while co-creator Jane Petro offered plastic surgery consults to visitors and New York performance artist Lily Pink sold “modern snakeoil.” The performances worked to engage viewers in the installation space with ideas regarding aging and the beauty industry’s false promises.

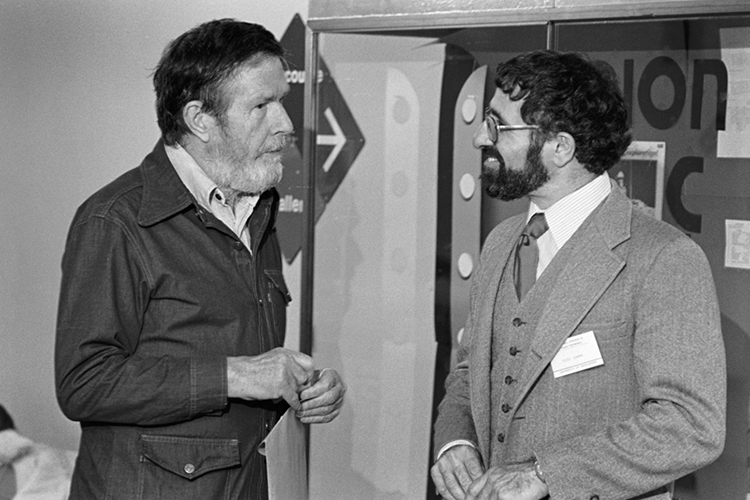

International Symposium on Post-Modern Performance

Nov. 17-20, 1976: This symposium was a real who’s who of avant-garde performers of the 1970s, but perhaps most well-known was John Cage, one of the most important composers of the 20th century. (His famous work “4’33”” was an entirely silent composition.) At this four-day conference held at UWM, he performed “Empty Words,” a spoken-word performance drawn from the journals of Henry David Thoreau. Other symposium participants hosting lectures and workshops included Jean-François Lyotard, Herbert Blau, Teresa de Lauretis and Umberto Eco.

Paul Aschenbach: ‘The Copernicus Stones’

June 25-29,1973: Paul Aschenbach became renowned for sculptures and installations that actively involved the public in their creation. In 1973 the Center for 20th Century Studies invited Aschenbach to create a piece called the Copernicus Stones on Summit Avenue in Milwaukee. Assembled over the course of four days by Aschenbach, his wife, June, his assistant Terry Dinnan, and many local residents and UWM students, the piece was in part intended as a reflection on time and experience.

Of the piece, Aschenbach had this to say: “The object stays in the community; after the sculptors leave, it carries on a longer, quieter dialogue with the people who encounter it. It is important that the object be as intense, as meaningful, as beautiful as the event which produced it.”

Paul Schrader, screening of ‘Taxi Driver’

March 27, 1976: Screenwriter Paul Schrader came to UWM in March 1976 for a screening of “Taxi Driver” (directed by Martin Scorsese), which had been released the month before. The film was an instant success, with Roger Ebert praising it as one of the best films he’d ever seen, and Schrader was well on his way to becoming a Hollywood mainstay. Schrader was also a film critic and wrote a book on film theory, “Transcendental Style in Film” (1972). At the event, Schrader discussed screenwriting and criticism with scholar Stephen Heath.

Schrader went on to pen three of Scorsese’s other Oscar-winning films: “Raging Bull” (1980), “The Last Temptation of Christ” (1988), and “Bringing Out the Dead” (1999), so this would have been a pretty important “get” for UWM at the time. And to put it in conversation with film theory: even better.