From “Star Trek” to the SETI program, humanity loves to speculate on a burning question: Is there alien life somewhere out there in the vast reaches of the universe?

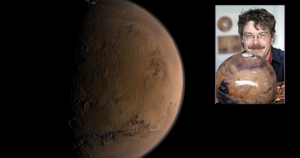

For Dirk Schulze-Makuch, the question isn’t so speculative: It’s his job. As a professor of planetary habitability and astrobiology at the Technical University Berlin, Germany, he searches for evidence of life on Mars and other extraterrestrial locations.

Schulze-Makuch, a German native who earned his PhD in geosciences from UWM, sat down to talk about his work and the possibility of intelligent life on planets beyond our own.

You earned your PhD in geosciences, but now you are an astrobiologist. How did you make the jump from one field to the other?

My PhD work was in hydrogeology with professor Doug Cherkauer in the Geosciences Department. Afterward, I took an assistant professor position at the University of Texas at El Paso to focus on hydrogeology and finding water in the desert southwest. There turned out to be quite a bit of overlap with finding life in the hyper-arid environment on Mars. With that connection, I got more and more interested in astrobiology.

Then, I received a fellowship from NASA using different kinds of methods – geophysical methods, mostly – to find water in arid environments, where the water table is very deep down. It was with the idea that on Mars, the environment would be very similar.

And where there is water, there may be life.

Yes. I am interested in extraterrestrial life and about other environments and conditions on other planets, like Mars, Venus, Jupiter’s moon Europa, and Saturn’s moon Titan. Even on exo-planets, we do some research.

When you say extraterrestrial life, I think many people picture little gray aliens. But you’re studying much smaller life, correct?

Of course, I’m also interested in more complex life, but 80 percent of my research is on microbial life. The approach that I take is that you cannot understand life without understanding the environment around it. They are so intertwined; one affects the other one.

Right now, most of my research is focused on Mars. On Mars, we would only expect microbial life. So, we are also working on life-detection methodologies. At some point, we are hoping that we will have a life-detection experiment on Mars and can send a probe. with our developed instrumentation. But it is a big challenge how to detect life in an extraterrestrial location.

One thing we do is look at the motility of microbes – the way they move, the characteristic patterns of it. Then we use algorithms to describe it. We can do that and distinguish between microbial movement and the random movement of tiny, inorganic particles because of wind or water changes. We are pretty good at detecting the difference, now. The problem we have more is how to distinguish between different types of bacteria.

How do you conduct these experiments? It’s easy to study life on Earth on Earth, but I think much harder to study life on other planets from here on Earth.

Right, that’s correct. But we can actually do quite a bit. I have in my lab a Mars simulation chamber so that we can simulate the conditions that exist on Mars. That brings us quite a bit closer to the problem.

The microbial movement will show under a microscope and we can distinguish it from a, let’s say, sand particle. If there is microbial life on Mars, it would do certain things that it would also do on Earth, so it’s somewhat comparable.

Are there Earth analogs to life on Mars?

We have conducted studies in the Atacama Desert. That is a very, very dry environment. In some areas, it rains maybe once every 10 years. How do microbes get their needed water over there? What those microbes do, is they are actually using the salt – there’s a lot of salt in the desert – and with the salt they can extract water directly from the atmosphere, from the relative humidity of the air. That way, they can get water even though it’s not raining at all.

This might be a good analog to Mars. We can imagine life might be hanging on on Mars in the same way. It’s an adaptation trait. We know that on Mars there’s a lot of salt – for example, in the southern highlands of Mars. We think that maybe there are microbes embedded in the salt, perhaps a few centimeters or millimeters below the surface, and that way they get water.

Of course, you have to keep in mind that the environment is quite a bit more extreme on Mars than in the Atacama Desert. It’s still very difficult. Nothing is easy. It would be a challenge for the microbes, and it will be a challenge for us to find it and prove it.

After your time at University of Texas-El Paso and other stints at American universities, you’re now a professor of astrobiology in Germany. Do you have a current research project that you’re working on?

We have several. One of my students works on the motility and behavior pattern of microbes. One of my postdocs is working on brines and salt solutions. We test out our favorite microbes – how much salt they can take and still survive. We actually have a record-holder. One particular yeast species can take the highest concentration of salt and still make a living.

One of my other students is comparing K-stars and G-stars. Our sun is a G-dwarf star, but there are a lot of K-dwarf stars out there that are less luminous than our sun, but may be preferable for having life-hosting planets around it.

In addition to your research papers, you’ve also authored several books. Can you tell us about your most recent book, The Cosmic Zoo?

I’m interested not only in microbial life, but also complex life and the evolution toward intelligence, and possibly technological intelligence. For Cosmic Zoo, I partnered up with William Baines. He is a biochemist. We said, how is it that humans became the dominant species on our planet? And if you rewound the tape of life, would it wind up again like that? So, we looked at all of the different evolutionary transitions, from single-cellular life to multicellular life, from prokaryotes to intelligent life. We looked at various kinds of intelligent life – like dolphins, apes, and octopuses. But there was only one species, us, that became technologically intelligent. And we wondered why that is and if it could happen again.

What we came up with is that there are multiple pathways to overcome those transitions like the one from singlecellular to multicellular life, and we think that if life originates on some other planet in the universe, and if that planet stays habitable long enough, then eventually there will be complex life on that planet.

That doesn’t mean technologically advanced life. We don’t know that really, because it’s only happened once on Earth. But, animal or plant-like life, we would expect.

In your opinion, is there a possibility that other life, analogous to humans, is out there somewhere in space?

Given this huge size of the universe – we have discovered by now more than 5,000 exoplanets and we think there will be billions out there – I would think that this is very likely.

Of course, the question is, how far away that life would be. The universe is incredibly big. It may be at such a distance that we will never know (about it). But I would be very surprised if we were the only ones thinking, why are we here and what is our place in the universe?

It might not be human, though. It might still be intelligent, but it might look very differently or act very differently. Also, we have had intelligent life on our planet for a relatively long time. The first octopus was already around more than 350 million years ago. We have dolphins that are very smart. Elephants, actually, are pretty smart too. There are apes, obviously, as well, and some birds that are very smart too, like crows or parrots. Of all of these, none have evolved to this stage of technological intelligence. We can’t really figure out why. So perhaps, after all, we are something quite special.

Stephen Hawking has famously said that if there is intelligent life out there, there’s a risk it would come to destroy us. What are your feelings about that?

He does have a point. If there is technologically intelligent life out there, then it is likely a social predator. I believe that because predators are usually more intelligent than prey. And social, because … if you think about what a single human could do, that’s really very limited. But because we work so well together, we can achieve a lot and build a spaceship, for example.

So, assuming that a technologically advanced alien exists, and would likely be social predators, they could in principle be a danger for us because even if there’s no ill will, there might be just a misunderstanding with communication. Think about it: For most animals, if they show their teeth, it’s a sign of aggression. But, for humans, we show our teeth and smile to show our affection.

So, I think Stephen Hawking has a point that we have to be very careful. We should not automatically assume they are friendly to us.