You may have never heard of Doré, but you’ve certainly seen his work.

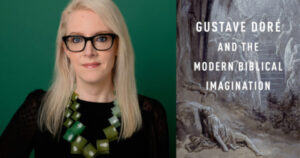

Gustave Doré was a French artist most known for his Biblical illustrations, showing everything from Moses with the Ten Commandments to the Passion of the Christ. And, says Sarah Schaefer, an assistant professor of art history at UWM, he’s the perfect lens to understand the staying power of religion, even as the world grew more secular.

It’s the subject of her new book, Gustave Doré and the Modern Biblical Imagination, which was published in September. Schaefer sat down to talk about her work, Doré’s cultural impact, and the surprising places you can find his work – even in Milwaukee.

Who was Doré? I don’t think I had heard of him before I saw your book.

He’s most known as an illustrator. He was born in 1832, and the key period of his production is from about the late 1850s until his death in 1883. He started off working in satirical or comicstyle newspaper illustration, and then shifted to more “serious” journalistic interpretation. He moved on from there to serious book illustration. He’s one of those artists who, if you don’t know his name – and his name is not very well known outside of art historical circles or the circles of book collectors – you have most certainly seen some of his work. He was very prolific. I’ve seen estimates that he created upwards of 100,000 images in his lifetime.

Some of his most famous illustrations are for Dante and the entirety of The Divine Comedy. Paradise Lost, Don Quixote, Tennyson. He was dedicated to illustrating all of what were considered the classic pieces of world literature in his time.

But he’s most known for his Biblical illustrations, right?

It’s likely that Doré’s Biblical imagery is the most reproduced Biblical imagery in the history of the Bible. He was probably the most famous artist in the world when he died in 1883 even though he’s not an artist whose name is well-known in America today – which is funny, because America is probably the place where his images are most widespread. You can find them everywhere.

In my case, I decided to focus specifically on his Bible illustrations. I’m using him as a lens to consider the Bible as it is understood and visualized in what we call ‘modernity’ – a period that for a long time was considered entirely secular, where religion and the Bible were relics of an early modern past. But that’s really not the case, and Doré is a figure through whom we can see the continued proliferation of the Bible happening on a global scale.

For sake of reference, when is the modern period?

The French Revolution (in 1789) is a really helpful starting point. One of (the French people’s) goals was to overturn the authority of the Church. All Church property in France became the property of the state. A lot of gold was melted down; relics were destroyed. One of my favorite stories from that period was that one of the relics, the bones of St. Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris and France – literally bone fragments – were put on trial and accused and convicted of misleading the public. They were publicly burned.

So, it seems like religion is being questioned, disregarded, even fought against much more starkly than it had been before. But, that’s just one particular moment in one particular space. When you move outside of Paris, outside of France, to places like Britain and Germany, Biblical scholarship and interest in the Bible becomes even more pervasive in the late 18th century and the early 19th century.

Today, Doré is everywhere – even here in Milwaukee. I understand there’s a Tiffany stained-glass window of a Doré at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church.

I decided to open the book by focusing on Doré and Milwaukee. My first time in Milwaukee, I came here to see the Tiffany stainedglass window. It’s the largest stained-glass window that the Tiffany company ever produced.

I started to think more about how many different reproductions or adaptations of Doré’s works there are here. I focus on four in the book’s introduction. One is the stained-glass window; one is a second edition of the Doré Bible illustrations that’s in the Milwaukee Public Library. The third is a painting that Doré didn’t do, most likely, but that someone did based on his illustrations, that is in the Haggerty Museum at Marquette. The fourth one is a paint-by-number based on one of his images of Moses that’s at Maria’s Pizza on Forest Home Avenue in Milwaukee.

I just love these four objects. They’re all super-fascinating. He’s in Milwaukee, but it’s also indicative of how he’s ubiquitous everywhere, and you just don’t know to look for it.

As you were researching your book, were there any discoveries that stood out to you?

Art historians are always looking for that object that’s been molding away in a storage cabinet in a museum whose importance hasn’t been highlighted before. For me, that was the primary archive of Doré’s letters in Strasbourg, France.

Typically, an artist would produce a design that would then be transferred to a wood-block that an engraver would then engrave. Doré just drew directly onto wood-blocks. The result meant that when the engraver took the block to engrave it, that drawing is destroyed. Both Doré’s original design and in most cases, the wood-blocks, are gone. We just don’t have them anymore.

But, through the foresight and ingenuity of what had to have been a number of people, his designs on the wood blocks, before they were engraved, were photographed and put into these bound volumes. … These are photographs of original drawings that don’t exist anymore. Some of these images were never published. When I saw these images for the first time, I was super-excited. This was at a time when digitization efforts were underway. Now you can go onto the National Library of France’s online catalog and see these photographs.

Why is it so important to understand Doré and how his illustrations fit in with religion and modernity?

Doré provides a really helpful lens because his work was so comprehensive and renowned. His work was absorbed by many different communities, in England, in France, in Germany, the Philippines. You see his works reproduced in a lot of Jewish works as well. It shows up everywhere, so it’s really helpful for illuminating how the Bible is adapted for modern contexts and how it is crucial not to just religious communities, but to culture as a whole.

(For example) Cecil B. DeMille, the maker of the film “The Ten Commandments,” took compositions basically straight of Doré’s illustrations. And he copped to that! A lot of early filmmakers did that. All of them were hugely indebted to Doré’s work.

By Sarah Vickery, College of Letters & Science